Additions will be checked before being published on the website and where possible will be forwarded to the person who submitted the original entries. Your contact details will not be forwarded, but they can send a reply via this messaging system.

please scroll down to send a message

CQMS. Harold Vickerman Hanson

British Army 2nd Btn. Yorkshire Regiment

from:Huddersfield

The Great War cast its shadow over my grandfather's life even before it began, because in August 1914 Harold Hanson went on a Cook's Tour of the Rhineland. It might be thought that this was not the best time to visit Germany, but the holiday had been booked months beforehand when the European situation had appeared quite stable. Everywhere the British party travelled they became increasingly alarmed at the sight of large-scale movements of German troops, which their German guide tried to reassuringly describe as 'just manoeuvres'. However, it was quite evident that Germany was mobilising for war, and the tourists were relieved when they left for home a day or two before the outbreak of hostilities, otherwise they would have faced spending the war in a Civilian Internment Camp in Germany.

My grandfather, being a Yorkshireman, volunteered to join the King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry and passed his army medical examination as A1 - i.e. fit for combat duty, in spite of the fact that his eyesight was so poor he had resigned from his school cricket team at the age of 13 because he could no longer see the ball! My grandfather was sent to a huge army camp on Salisbury Plain for his basic training where he vividly remembers bayonet practice on rope-hung sacks of sawdust, and the drill sergeant barking out the order 'And before you withdraw the bayonet - give it a twist!' One winter's morning in the 1970's, I was volunteered by my office manager to help him light the central heating boiler when the stoker, a local man, hadn't turned up. My task was to chop firewood for which I was handed a World War One bayonet, which was so razor sharp that with very little effort I soon had a large pile of firewood ready. Remembering my grandfather's training, I shuddered to imagine thrusting this lethal weapon into a human body!

Not long after the commencement of my his training, a very unpleasant event occurred. Fresh rations suddenly and mysteriously disappeared, to be replaced by what the army called hard tack - large square biscuits, nicknamed dog biscuits by the men. The absence of fresh food was entirely owing to the incompetence and indifference of the military authorities - after all, the recruits were not stationed in a remote outpost of the British Empire, but in south-west England! After a few days of this treatment, rioting broke out in one of the barrack huts which were grouped around a large square quadrangle. The riot quickly spread to all the other huts. Furniture and windows were smashed and the dog biscuits used as projectiles, being hurled around indiscriminately. My grandfather, not wishing to participate in the riot or to be hit by one of the fearsome biscuits, dropped to his knees. He had no sooner done so than one of his comrades received one of the biscuits full on the forehead, causing a deep gash from which blood spurted. The man was knocked unconscious by the blow, and fell to the floor at the side of my grandfather, who crawled to one of the windows. Looking out he saw a group of officers standing huddled together in the middle of the quadrangle, heads together, discussing the deteriorating situation. Every now and again, one of the officers would turn and look apprehensively at the huts full of rioting men. Eventually the officers dispersed without attempting to approach any of the huts to remonstrate with the recruits - they were obviously afraid to do so, the men being in such an ugly mood. However, the riot had the desired effect because first thing next morning there was fresh food for breakfast - and plenty of it! No disciplinary action was taken against any of the rioters - the military authorities preferring to pretend that the riot had never happened. Doubtless they realised that the men had been pushed too far - and they wouldn't want the newspapers getting wind of the affair!

It was during this time that my grandfather's deficient eyesight was finally discovered - on the firing range! Each recruit had been given a numbered target to aim at, and the accuracy was plotted by monitors. My grandfather had been firing away for a few minutes when the Captain in command of the firing range came up behind him and demanded 'Which target number are you aiming at?'

My grandfather looked round in some surprise and replied 'I'm aiming at my designated target - No. 2.'

The Captain then said 'Well my monitors tell me that your shots are hitting target No. 4. You had better get along to the M.O. (Medical Officer) and have your eyesight tested.'

The M.O. was going to write out a medical discharge there and then, but it had to be countersigned by a second M.O. who, being a brusque, no-nonesense type said “Oh there’s no need to discharge this man, he's quite fit enough for non-combat duties.'

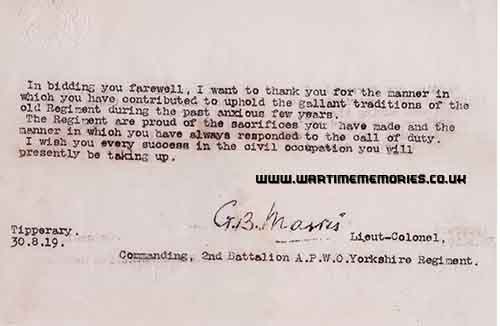

Accordingly, my grandfather's civilian record was examined and he was awarded the rank of C.Q.M.S. (Company Quatermaster Sergeant) and then posted to Alexandra, Princess of Wales's Own Yorkshire Regiment a.k.a. The Green Howards. This meant that my grandfather had to bid farewell to the other 29 comrades in his barrack hut, everyone of which, my grandfather subsequently learned after the war, had been either killed or wounded. Not one had come through the war unscathed.

As C.Q.M.S. my grandfather's duties were varied. On one occasion for instance, he was ordered to oversee a group of Conscientious Objectors who had been set to work digging latrines (toilets). On another occasion he was required to dispose of a huge quantity of discarded uniforms which were dumped on his quadrangle in large rotting heaps. This didn't please his Colonel who demanded 'What's all this bloody mess, Quarters?' My grandfather's response was to ask the Colonel to look more closely at the heaps, upon which he exclaimed 'Good Heavens, they're moving!' The heaps of rotting uniforms were so heavily infested with lice that the constant wriggling of the creatures was making each pile slowly and rhythmically rise and fall, which gives some indication of the appalling conditions in the front-line trenches. From time to time my grandfather received inducements to sell army supplies on the black market, but being a man of scrupulous honesty he always firmly rebuffed such overtures.

With the declaration of the Armistice, my grandfather looked forward to demobilisation, and to be re-united with my grandmother, whom he had married a year previously. However, his hopes were dashed when he was told he was to be posted to Dublin for several months as part of the British Forces garrisoned there, in order to counter the activities of the Irish Nationalists.

My grandfather found the atmosphere in Dublin was poisonous with hatred towards the British to such an extent that off-duty soldiers were under strict orders not to walk through the city streets in groups of less than three. Accordingly, one day he was walking along with two other sergeants when, passing two Irishmen on the pavement, one of the Irishmen made a derogatory remark about the British. Unfortunately, one of the other two sergeants had a quick temper and spontaneously lashed out with his fist, knocking the offending Irishman flat on his back. This was the signal for every Irishman in the vicinity to pounce on the three sergeants, and things would have gone very badly for them had not providence been on their side in the form of a Public House on the corner of the street which just happened to be full of off-duty Seaforth Highlanders, who liked nothing better than a good scrap, and on hearing the rumpus in the street outside, they piled out of the pub, and very soon the entire street was full of men knocking the daylights out of each other. My grandfather took this welcome intervention as an opportunity to make his escape because, although he was a good amateur boxer, he boxed at Bantam Weight, so he was no match for a burly Irishman. However, he was left with the prospect of making his own way back to the barracks along streets where every British soldier was a marked man, and he couldn't afford to hurry or look nervous - fortunately the journey passed without incident.

Although my grandfather did not enjoy his sojourn in Dublin, there was one bright note. The food in the sergeants' mess was prepared by local women, instead of the usual army cooks, and I remember my grandfather telling me that these ladies cooked some 'wonderfully tasty meals' - so at least he was well fed!

Following eventual demobilisation, my grandfather expected to get his old job back without any trouble because the Government had made it very clear to employers from the very beginning of the War that jobs of men serving in the forces were to be kept open for them on their return. However, in spite of having given exemplary service, my grandfather found his employers strangely reluctant to re-employ him. As my grandmother and baby daughter (my mother) had been living with my great-grandparents during the war, my grandfather had to find both a home and an income, and jobs at the time were hard to come by. Therefore he had to swallow his pride and turn to a Veterans' Association who were successful in applying pressure on his employers. He later learned that his job had been taken by a man who had not served in the war but was a relative of one of the Company Directors. This episode graphically illustrates the difficulties soldiers faced when returning to civilian life.

While clearing out my grandparents' bungalow after their deaths within a month of each other, I came across a momento from my grandfather's army days - the casing of a hand grenade that both my mother and myself had played with as children. When a scrap metal dealer came, I tossed the grenade on to the pile of metal objects, remarking with a smile, 'Here's an extra bit of metal for you.' I laughed at his evident alarm and reassured him, 'It's quite harmless, it's hollow inside.' He still looked very dubious, but he took it with the rest and drove away. That same evening my mother received a phone call from a police sergeant who asked her if there was any more live ammunition lying around the property. Apparently the scrap metal dealer had handed in the grenade at a local police station and the Bomb Squad had successfully detonated it. As a child I had, from time to time, considered removing the pin of the grenade in order to ascertain how the pieces of the casing fitted together. I had always been deterred from this course of action by reasoning that the pin fitted so tightly that I might not be able to restore it to its original position. Of course, if I had pulled out the pin I should not now be writing this account, and many years after the signing of the Armistice, the Great War would have claimed yet another casualty.

.jpg)

.jpg)