|

This website uses cookies. By continuing to use this site you agree to accept cookies. If you enjoy this site please consider making a donation.

Features Submissions Information World War 1 One ww1 wwII greatwar great 1914 1918 first battalion regiment |

The Wartime Memories Project - The Great War - Day by Day

30th March 1916

On this day:

- Some Shelling 6th County of London Brigade RFA at Carency report Ablain and the slopes of Lorette shelled with 5.9s and Howitzers between 1245 and 1500. About 68 shells were fired intermittently. This shelling was most active about 1500 and then died down. Three miniature balloons floated over 16th London Battery in a north easterly direction at about 1800, no doubt testing wind levels and direction. Except for some slight shelling the rest of the day was quiet. Aeroplanes were very active all day. A Flamenwerfer (flame thrower) demonstration was held at Gowry School which 28 officers & other ranks attended.

War Diaries- Schütte-Lanz Airship.

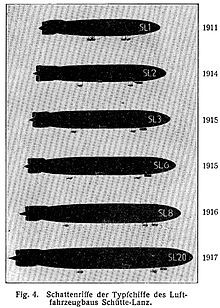

Schütte-Lanz Airship type silhouettes

Schütte-Lanz SL8

- First Flight: 30th March 1916

- Length: 174 metres (571 ft)

- Diameter: 20.1 metres (66 ft)

- Gas Capacity: 38,780 cubic meters

- Performance: 96.8 km/h

- Payload: 18.7 tonnes

- Engines: 4 Maybach 960 hp/716 kW total

Naval airship based at Seddin. Carried out 34 reconnaissance missions and three bombing raids, carrying 4,000 kg of bombs each mission. Held the record for the greatest number of combat missions of any Schütte-Lanz airship. Decommissioned due to age on the 20th November 1917.

John Doran- Schütte-Lanz Airship. Schütte-Lanz SL9

- First Flight: 30th March 1916

- Length: 174 metres (571 ft)

- Diameter: 20.1 metres (66 ft)

- Gas Capacity: 38,780 cubic meters

- Performance: 92.9 km/h

- Payload: 19.8 tonnes

- Engines: 4 Maybach 960 hp/716 kW total

Naval airship based at Seddin. Carried out 13 reconnaissance missions and four bombing raids carrying 4,230 kg of bombs each mission. Crashed in the Baltic, possibly after lightning strike on the 30th March 1917.

John Doran- Schütte-Lanz Airship. Schütte-Lanz SL10

- First Flight: 30th March 1916

- Length: 174 metres (571 ft)

- Diameter: 20.1 metres (66 ft)

- Gas Capacity: 38,800 cubic meters

- Performance: 90 km/h

- Payload: 21.5 tonnes

- Engines: 4 Maybach 960 hp/716 kW total

Army airship based at Yambol, Bulgaria.Carried out a 16 hour reconnaissance mission. Disappeared during a subsequent attack on Sevastopol, possibly due to bad weather on the 28th July 1916.

John Doran- Russian Hospital Ship

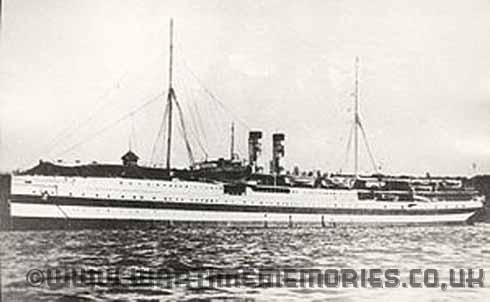

HS Portugal - Russian Hospital Ship in the Black Sea

Russian hospital ship Portugal (Russian: госпитальное судно "Португаль") was a steam ship originally built by a French shipping company, but requisitioned for use as a Russian hospital ship during the First World War. On the 30th March 1916 she was sunk by a torpedo from the German U-boat U-33.

History[edit]

She was originally built in 1886 for the Brazil and River Plate Line of the Messageries Maritimes Company. She was chartered or purchased by the Russians for use as a hospital ship in the Black Sea.

Sinking.

Georgian princess Aneta Andronnikova was one of the Red Cross nurses who died in the Portugal incident. On the 30th March 1916, the Portugal was towing a string of small flat-bottomed boats to ferry wounded from the shore to the ship. Off Rizeh, on the Turkish coast of the Black Sea, she had stopped as one of the small boats was sinking and repairs were being made. The ship was not carrying wounded at the time, but had a staff of Red Cross physicians and nurses on board, as well as her usual crew.

The ship's crew saw a periscope approaching the vessel but as the ship was a hospital ship and protected by the Hague conventions no evasive actions were taken. Without warning the submarine fired a torpedo which missed. The U-boat, U-33, came around again fired a torpedo from a distance of 30 feet, which hit near the engine room, breaking the ship into two pieces.

The Vperiod.

On the 8th July 1916, another Russian hospital ship, named Vperiod (Вперёд; also transcribed, French-style, as Vperiode) was sunk between Rizeh and Batum, allegedly by German U-boat U-38. The boat was not carrying wounded, as it was on its trip to the frontline. Seven people died, the rest were saved.

The Russian government claimed that Turkish forces sank the Portugal and the Vperiod. The Turkish government replied that both ships were sunk by mines.

Account of Sinking of SS Portugal.

The submarine approached the "Portugal" quietly and discharged a torpedo, which missed its aim. Then it circled round and discharged a second at the other side of the vessel, from some 30 or 40 feet away. This second torpedo struck the Portugal amidships, in the engine-room. There was a violent explosion; the hull broke in two, and most of those on board were precipitated into the whirlpool between the two halves. With a still more violent explosion the boilers blew up, and the bow and stern fragments of the "Portugal" went down simultaneously. Forty-five of the Red Cross staff were lost, twenty-one of whom were nurses. Twenty-one men were lost out of the Russian crew, and nineteen out of the French. Thus eighty-five of those on board perished altogether.

Here is an account of the outrage by one of the survivors—Nikolai Nikolaevitch Sabaev, secretary to the Russian Red Cross Society's Third Ambulance Detachment with the Army of the Caucasus:—

" At about 8 o'clock in the morning, somebody on board shouted out, 'submarine boat.' At first, this news did not produce any panic; on the contrary, everybody rushed on deck to be the first to see the submarine. It never entered anybody's head to suppose that a submarine would attack a hospital ship, sailing under the flag of the Red Cross. I went on to the upper deck, and noticed the periscope of a submarine, moving parallel with the steamer at a distance of about 170 or 200 feet. Having reached a point opposite to the middle of the 'Portugal,' the periscope disappeared for a short time, then reappeared, and the submarine discharged a torpedo. I descended from the upper deck, and ran to the stern, with the intention of jumping into the sea. When, however, I noticed that most of the people on deck had life-belts, I ran into saloon No. 5, seized a life-belt, and put it on, but then I fell down, as the 'Portugal' was sinking at the place where she was broken in two, while her stem and stern were going up higher all the time. All round me unfortunate sisters of mercy were screaming for help. They fell down, like myself, and some of them fainted. The deck became more down-sloping every minute, and I rolled off into the water between the two halves of the sinking steamer. I was drawn down deep into the whirlpool, and began to be whirled round and thrown about in every direction. While under the water, I heard a dull, rumbling noise, which was evidently the bursting of the boilers, for it threw me out of the vortex about a sazhen, or 7 feet, away from the engulfment of the wreck. The stem and stern of the steamer had gone up until they were almost at right angles with the water, and the divided steamer was settling down. At this moment I was again sucked under, but I exerted myself afresh, and once more rose to the surface. I then saw both portions of the 'Portugal' go down rapidly, and disappear beneath the flood. A terrible commotion of the water ensued, and I was dragged under, together with the 'Portugal.' I felt that I was going down deep, and for the first time I realized that I was drowning.

. . . My strength failed me, but I kept my mouth firmly shut, and tried not to take in the water. I knew that the moment of death from heart failure was near. It so happened, however, that the disturbance of the water somewhat abated, and I succeeded in swimming up again. I glanced round. The ' Portugal ' was no more. Nothing but broken pieces of wreck, boxes which had contained our medicaments, materials for dressing wounds, and provisions were floating about. Everywhere I could see the heads and arms of people battling with the waves, and their shrieks for help were frightful. . . . 8 or 9 sazhens (56 or 63 feet) away from where I was, I saw a life-saving raft, and I swam towards it. Although my soddened clothes greatly impeded my movements, I nevertheless reached the raft, and was taken on to it. About 20 persons were on it already, exclusively men. Amongst them was* the French mate, who assisted the captain of the ' Portugal, ' and he and I at once set about making a rudder out of two of the oars which were on the raft, and we placed an oarsman on each side of it. We had been going about 8 minutes when we saw the body of a woman floating motionless, and dressed in the garb of a sister of mercy. . . . We then raised her on to the raft. She was unconscious, quite blue, and with only feeble signs of life. . . . She at last opened her eyes and enquired where she was. I told her that she was saved. Soon, however, she turned pale, said she was dying, and gave me the address of her relatives, to inform them of her death. She began to spit blood, and was delirious, but gradually a better feeling returned, and she was soon out of danger. We went on rowing towards the shore for a considerable time. . . . At last a launch, towing a boat full of the rescued, took us also in tow, and we reached the shore in safety. The hospital ship 'Portugal' was painted white, with a red border, all around. The funnels were white with red crosses, and a Red Cross flag was on the mast. These distinguishing signs were plainly visible and there can be no doubt whatever that they could be perfectly well seen, by the men in the submarine. The conduct of the submarine itself proves that the men in it knew that they had to do with a hospital ship. The fact of the submarine having moved so slowly shows that the enemy was conscious of being quite out of danger."

John Doran- Leeds Pals suffer first casualty in action (Acting Sgt)Corporal Frank Bygott was the first Leeds Pal to be killed in Action. The battalion had arrived near Serre on 29th March. That evening he took part in a raid on German lines 250 yards to their front. During the return he received a fatal wound - from 'friendly MG fire.

- Heavy Thaw

- Under Heavy Bombardment

- Thunderstorm

- Change of Billets

- In Reserve

- Rest and Work

- Open warfare exercise

- Snipers

- Reliefs Complete

- orders

- Aircraft

- Training

- Large Shells Wanted

- Reliefs

- Quiet

- A German MG Legs It

- Postings

- Route March

- Enemy Active

- Transfers

- In Billets

- Aircraft Lost

- Aircraft Lost

- Aircraft Lost

- Aircraft Lost

- Engine Faileur

- Training

- Routine

- On the March

- Mortars Active

- Reliefs

- The bath's at Reninghelst were placed at disposal of Battalion for the day.

- Working Parties 1 Coy from 7th Buffs are employed making tramway from Bray

7th Buffs war diary WO95/2049- Flammenwerfer demonstrations

- Some Fatigues

- Platoon training.

- Enemy Artillery Active

- Into Billets

- Armourer Sgt. inspected the Arms.

Can you add to this factual information? Do you know the whereabouts of a unit on a particular day? Do you have a copy of an official war diary entry? Details of an an incident? The loss of a ship? A letter, postcard, photo or any other interesting snipts?If your information relates only to an individual, eg. enlistment, award of a medal or death, please use this form: Add a story.

Killed, Wounded, Missing, Prisoner and Patient Reports published this day.

This section is under construction.

Want to know more about 30th of March 1916?

There are:45 items tagged 30th of March 1916 available in our Library

These include information on officers, regimental histories, letters, diary entries, personal accounts and information about actions during the Great War.

Remembering those who died this day, 30th of March 1916.

Sgt. Robert Leggat. 9th Btn. Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) Read their Story. Pte. Hiram Ashford Southgate. DCM. 2nd Battalion Suffolk Regiment Read their Story. Add a name to this list.

Select another Date

The free section of The Wartime Memories Project is run by volunteers.

This website is paid for out of our own pockets, library subscriptions and from donations made by visitors. The popularity of the site means that it is far exceeding available resources and we currently have a huge backlog of submissions.

If you are enjoying the site, please consider making a donation, however small to help with the costs of keeping the site running.

Hosted by:

Copyright MCMXCIX - MMXXV

- All Rights Reserved -We do not permit the use of any content from this website for the training of LLMs or for use in Generative AI, it also may not be scraped for the purpose of creating other websites, books, magazines or any other forms of media.