|

|

|

HMS Kent

8th December 1914 Battle of the Falklands

German East Asia Squadron leaving Valparaiso, Chile. (4 Nov 1914) The Battle of the Falkland Islands took place on the 8th December 1914 during the First World War in the South Atlantic. The British, suffering a defeat at the Battle of Coronel on 1 November, had sent a large force to track down and destroy the victorious German cruiser squadron. Admiral Graf Maximilian von Spee commanded the German squadron which consisted of two armoured cruisers SMS Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, three light cruisers SMS Nürnberg, Dresden and Leipzig together with three auxiliarie.

They attempted to raid the British supply base at Stanley in the Falkland Islands.

A larger British squadron, consisting of two battlecruisers HMS Invincible and Inflexible, three armoured cruisers HMS Carnarvon, Cornwall and Kent and two light cruisers HMS Bristol and Glasgow had arrived in the port only the day before. Visibility was at its maximum, the sea was calm with a light northwesterly breeze and a bright sunny day. The German squadron had been detected early on and by nine o'clock that morning the British were in hot pursuit of the five German vessels who had taken flight to the southeast.

The only ships to escape were the light cruiser Dresden and the auxiliary Seydlitz- all the others were sunk. The British battlecruisers each mounted eight 12 inch guns, whereas Spee's heaviest ships (Scharnhorst and Gneisenau), were only equipped with eight 8.3 inch guns. Additionally, the British battlecruisers could make 29.3 mph against Spee's 25.9 mph. So the British battlecruisers could not only outrun their opponents but significantly outgun them too. The old pre-dreadnought battleship, HMS Canopus, had been grounded at Stanley to act as a makeshift defence battery for the area.

At the outbreak of hostilities in World War One, the German East Asian squadron, which Admiral Spee commanded, was heavily outnumbered by the Royal Navy and the Japanese Navy. The German High Command realised that the Asian possessions could not be defended and that the squadron might not survive. Spee therefore tried to get his ships home via the Pacific and Cape Horn, but was pessimistic of their chances. Following von Spee's success at Coronel off the coast of Valparaíso, Chile, where his squadron sank the cruisers HMS Good Hope and Monmouth, von Spee's force put into Valparaíso. As required under international law for belligerent ships in neutral countries, the ships left within 24 hours, moving to Mas Afuera, 400 miles off the Chilean coast. There they received news of the loss of the cruiser SMS Emden, which had previously detached from the squadron and had been raiding in the Indian Ocean. They also learned of the fall of the German colony at Tsingtao in China, which had been their home port. On 15 November, the squadron moved to Bahia San Quintin on the Chilean coast, where 300 Iron Crosses second class were awarded to the crew, and an Iron Cross first class to Admiral Spee. Spee was advised by his officers to return to Germany if he could. His ships had used half their ammunition at Coronel, and had difficulties obtaining coal. Intelligence reported the British ships HMS Defence, Cornwall and Carnarvon were stationed in the River Plate and that there were no British warships at Stanley. Spee had been concerned about reports of a British battleship, Canopus, but its location was unknown.

On 26 November, the squadron set sail and reached Cape Horn on the 1st December, anchoring at Picton Island for 3 days coaling from acaptured British collier, the Drummuir. On 6 December, the British vessel was scuttled and the crew transferred to the auxiliary Seydlitz. Spee proposed to raid the Falkland Islands before turning north to sail up the Atlantic back to Germany even though it was unnecessary and opposed by three of his captains.

On the 30th October, retired Admiral of the Fleet Sir John Fisher was reappointed First Sea Lord to replace Admiral Prince Louis of Battenberg.

On the 3rd November, Fisher was advised that Spee had been sighted off Valparaíso and acted to reinforce Cradock by ordering Defence,to join his squadron. On the 4th November, news of the defeat at Coronel arrived. As a result, the battlecruisers Invincible and Inflexible were detached from the Grand Fleet and sailed for Plymouth to prepare for overseas service.

Chief of Staff at the Admiralty was Vice-Admiral Doveton Sturdee with whom Fisher had a long-standing disagreement, so he took the opportunity to appoint Sturdee as Commander-in-Chief, South Atlantic and Pacific, to command the new squadron from Invincible. On 11 November, Invincible and Inflexible left Devonport. Repairs to Invincible were incomplete and she sailed with workmen still on board. The ships travelled at a reduced 12 mph as running at high speed used significantly more coal, so to complete the long journey it was necessary to travel at the most economic speed.

The two ships were also heavily loaded with supplies. Sturdee arrived at the Abrolhos Rocks on the 26th November, where Rear Admiral Stoddart awaited him with the remainder of the squadron. Sturdee announced his intention to depart for the Falkland Islands on 29 November. From there, the fast light cruisers Glasgow and Bristol would patrol seeking Spee, summoning reinforcements if they found him. Captain Luce of Glasgow, who had been at the battle of Coronel persuaded Sturdee to depart a day early.

The squadron was delayed during the journey for 12 hours when a cable towing targets became wrapped around one of Invincible's propellers, but the ships arrived on the morning of 7 December. The two light cruisers moored in to the inner part of Stanley Harbour, while the larger ships remained in the deeper outer harbour of Port William. Divers set about removing the offending cable from Invincible, Cornwall's boiler fires were extinguished to make repairs, and Bristol had one of her engines dismantled. The famous ship SS Great Britain, reduced to a coal bunker, supplied coal to Invincible and Inflexible. The armed merchant cruiser Macedonia was ordered to patrol the harbour, while Kent maintained steam ready to replace Macedonia the next day, 8th December. Spee's fleet arrived in the morning of the same day.

Two of Spee's cruisers—Gneisenau and Nürnberg—approached Stanley first and, at that time, the entire British fleet was still coaling. Some believe that, had Spee pressed the attack, Sturdee's ships would have been easy targets. Any British ship trying to leave would have faced the full firepower of the German ships and having a vessel sunk might also have blocked the rest of the British squadron inside the harbour. Fortunately for the British, the Germans were surprised by gunfire from an unexpected source as Canopus, which had been grounded as a guardship and was hidden behind a hill, opened fire. This was enough to check the Germans' advance. The sight of the distinctive tripod masts of the British battlecruisers confirmed that they were facing a better-equipped enemy. Kent was already making her way out of the harbour and had been ordered to pursue Spee's ships. Made aware of the German ships, Sturdee had ordered the crews to breakfast, knowing that Canopus had bought them time while steam was raised. To Spee, with his crew battle-weary and his ships outgunned, the outcome seemed inevitable. Realising his danger too late, and having lost any chance to attack the British ships while they were at anchor, Spee and his squadron dashed for the open sea. The British left port around 1000. Spee was ahead by 15 miles but there was a lot of daylight left for the faster battlecruisers to catch them.

It was 1300 when the British battlecruisers opened fire, but it took them half an hour to get the range of Leipzig. Realising that he could not outrun the British ships, Spee decided to engage them with his armoured cruisers to give the light cruisers a chance to escape. They turned to fight just after 1320. The German armoured cruisers had the advantage of a freshening north-west breeze which caused the funnel smoke of the British ships to obscure their targets practically throughout the action. Despite initial success by Scharnhorst and Gneisenau in striking Invincible, the British capital ships suffered little damage. Spee then turned to escape, but the battlecruisers came within extreme firing range 40 minutes later.

Invincible and Inflexible engaged Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, while Sturdee detached his cruisers to chase Leipzig and Nürnberg. Inflexible and Invincible turned to fire broadsides at the armoured cruisers and Spee responded by trying to close the range. His flagship Scharnhorst suffered extensive damage with funnels flattened, fires and developed a list. The list became worse at 1604, and she sank by 1617. Gneisenau continued to fire and evade until 1715, by which time her ammunition had been exhausted, and her crew allowed her to sink at 1802. During her death throes, Admiral Sturdee continued to engage Gneisenau with his two battlecruisers and the cruiser Carnarvon seemingly ignoring the escaping Dresden. 190 of Gneisenau's crew were rescued from the water. The battlecruisers had received about 40 hits, with one man killed and four injured. Meanwhile, Nürnberg and Leipzig had run from the British cruisers. Nürnberg was running at full speed while the crew of the pursuing Kent were pushing her boilers and engines to the limit. Nürnberg finally turned for battle at 1730. Kent had the advantage in shell weight and armour. Nürnberg suffered two boiler explosions around 1830, giving further advantage in speed and manoeuvrability to Kent. The German ship then rolled over at 1927 after a long chase. The cruisers Glasgow and Cornwall had chased down Leipzig. Glasgow closed to finish Leipzig which had run out of ammunition but was still flying her battle ensign. Leipzig fired two flares, so Glasgow ceased fire. At 2123, more than 80 miles southeast of the Falklands, she also rolled over, leaving only 18 survivors.

The British suffered only very light casualties and damage whereas Admiral Spee and his two sons were among the German dead. There were 215 rescued German survivors who became prisoners on the British ships. Most were from the Gneisenau, nine were from Nürnberg and 18 were from Leipzig. There were no survivors from Scharnhorst. Of the known German force of eight ships, two escaped, the auxiliary Seydlitz and the light cruiser Dresden, which roamed at large for a further three months before she was cornered by a British squadron off the Juan Fernández Islands on 14 March 1915. After fighting a short battle, Dresden's captain evacuated his ship and scuttled her by detonating the main ammunition magazine. As a consequence of the battle, German commerce raiding on the high seas by regular warships of the Kaiserliche Marine was brought to an end. However, Germany put several armed merchant vessels into service as commerce raiders until the end of the war.

John Doran

7th Mar 1915 Rendezvous at Sea

14th March 1915 Battle of Más a Tierra 1915 The Battle of Más a Tierra was a First World War sea battle fought on 14 March 1915, near the Chilean island of Más a Tierra, between a British squadron and a German light cruiser. The battle saw the last remnant of the German East Asia Squadron destroyed, when SMS Dresden was cornered and sunk in Cumberland Bay.

Background

After escaping from the Battle of the Falkland Islands, SMS Dresden and several auxiliaries retreated into the Pacific Ocean in an attempt to commence raiding operations against Allied shipping. These operations did little to stop shipping in the area, but still proved troublesome to the British, who had to expend resources to counter the cruiser. On 8 March, his ship low on supplies and in need of repairs, the captain of the Dresden decided to hide his vessel and attempt to coal in Cumberland Bay near the neutral island of Más a Tierra. By coaling in a neutral port rather than at sea, Dresden's Captain Lüdecke gained the advantage of being able to intern the ship if it was discovered by enemy vessels. British naval forces had been actively searching for the German cruiser and had intercepted coded wireless messages between German ships. Although they possessed copies of captured German code books, these also required a "key" which was changed from time to time. However, Charles Stuart, the signals officer, managed to decode a message from Dresden for a collier to meet her at Juan Fernandez on 9 March. A squadron made up of the cruisers HMS Kent and Glasgow along with the auxiliary cruiser Orama cornered the Dresden in the bay on 14 March, challenging it to battle.

Battle

Glasgow opened fire on Dresden, damaging the vessel and setting it afire.

After returning fire for a short period of time, the captain of Dresden decided the situation was hopeless as his vessel was vastly outgunned and outnumbered, while stranded in the bay with empty coal bunkers and worn out engines. Captain Lüdecke gave the order to abandon and scuttle his vessel.

The German crew fled the cruiser in open boats to reach the safety of the island, which was neutral territory. The British cruisers kept up their fire on Dresden and the fleeing boats until the light cruiser eventually exploded, but it is unclear whether the explosion was caused by the firing from the British ships or from scuttling charges set off by the Germans.

After the ship exploded, the British commander ordered his ships to capture any survivors from Dresden. Three Germans were killed in action and 15 wounded. The British suffered no casualties.

Aftermath

With the sinking of Dresden, the last remnant of the German East Asian Squadron was destroyed, as all the other ships of the squadron had been sunk or interned. The only German presence left in the Pacific Ocean was a few isolated commerce raiders, such as SMS Seeadler and Wolf. Because the island of Más a Tierra was a possession of Chile, a neutral country, the German Consulate in Chile protested that the British had broken international law by attacking an enemy combatant in neutral waters.

The wounded German sailors were taken to Valparaíso, Chile for treatment, where one later died of wounds received during the action. The 315 of Dresden's crew who remained were interned by Chile until the end of the war, when those who did not wish to remain in Chile were repatriated to Germany. One of the crew—Lieutenant Wilhelm Canaris, the future admiral and head of Abwehr — escaped internment in August 1915 and made it back to Germany, where he returned to active duty in the Imperial Navy.

John Doran

23rd Aug 1916 Kentish Gazette Sixpenny Fund

4th June 1918 Hospital ship

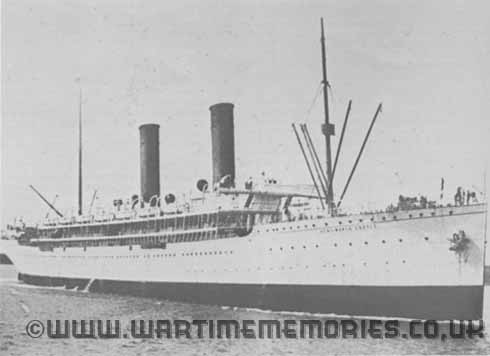

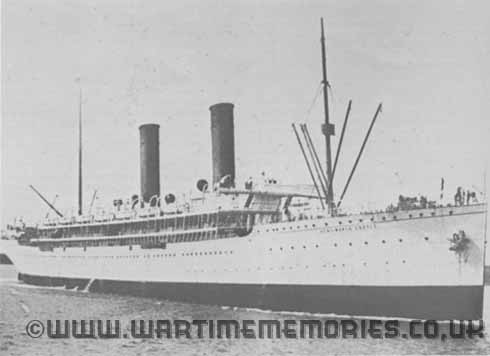

RMS Kenilworth Castle. With acknowledgement to Ships of South Africa, by Marischal Murray, (Oxford University Press and Humphrey Milford, 1933). RMS Kenilworth Castle. 1904-1936. Builders: Harland & Wolff, Belfast(yard no. 356) Order No.: 118433. Launched: 5th December 1903. Completed: May 1904, arrived Cape Town June 14th May 1904. Tonnage: 12,974 gross, 6,463 net. Dimensions: length 570.2 x beam 64.7 x depth 38.6 feet. Engines: Quadruple expansion by builder, 2,175 h.p., 12,000 i.h.p., speed 16.5 knots. Passengers:255 1st., 269 2nd., 270 3rd., Reefer Space: 17,206 cu.ft., (1921: 45,642 cu.ft. 1928: 140,982 cu.ft.).

World War 1.

- 1914, August 11th., requisitioned as a troop ship and also used as hospital ship.

- 1918, one voyage to Australia repatriating troops.

- 1918, June 4th., 35 miles off Plymouth collided with destroyer HMS Rival while zig-zagging. Depth charges of destroyer exploded under the Kenilworth's bow. (see Captain C.S.G Keen biography Ch.4). The Kenilworth Castle just managed to get to Plymouth where she sank on a mud bank.

- 1919, Returned to mail service.

The Kenilworth Castle Incident 1918.

The writer of this letter (Bracken was her surname, as the nurses were usually addressed by their surnames) addressed to Miss Helen Wrensch (now Mrs Gilfillan) was one of 36 nurses aboard the RMS Kenilworth Castle in June 1918. Homeward bound to England in company with the Durham Castle she was being convoyed up the English Channel with an escort of the cruiser Kent and five destroyers when she met with a mishap of an unusual nature.

Marischal Murray reported the incident in Ships and South Africa (OUP, London, 1933). 'At 0030 am on the morning of June 4th the Kent was due to leave the convoy, Plymouth being some 35 miles distant. In the darkness of the night - all ships, of course, were sailing without lights - the Kent changed her course according to plan, but some misunderstanding arose, and within a few minutes she was bearing down on the Kenilworth Castle. In order to avoid a collision, the helm of the mail steamer was rapidly put over and she swung clear of the Kent only to collide with the destroyer Rival cutting off that vessel's stern. Unfortunately, on the stern of the Rival, were several depth charges which were meant for the discomfort of German submarines. These, however, exploded with terrific force underneath the Kenilworth Castle, causing a gaping hole in the hull. The water rushed in forward, and before long the mail steamer was well down by her bows.

On board there was a certain amount of confusion. Everyone believed that the Kenilworth Castle had been torpedoed. As the bulkheads were holding it was not thought necessary to put the passengers in the boats. Through some misunderstanding, however, a few boats were lowered. Two of these were swamped, and, as a result, 15 persons were drowned, including some of the nurses on board. One of the nurses lost was named Black and is the 'poor little Black' referred to by the writer.

'The Kenilworth Castle, meanwhile, limped towards port, and by 8 am she had reached Plymouth where her passengers were put ashore. She herself was sent to the dockyards for repairs, and it was only after a considerable time had elapsed that she was able once again to put to sea.

Letter.

29th June 1918

Dear old Wrensch,

I just loved you for writing so soon - your letter came on the Kenilworth in a sloppy condition and marked 'Damaged by sea'. The same description applies to myself, I feel very much damaged by sea. Of course you know all about the accident to the Kenilworth and that poor little Black is drowned. I expect you all felt horrid when you read of the affair and I should think girls will not be quite so anxious to go overseas and certainly parents will not consent so readily. Of course we are soldiers in a way and soldiers must take risks. I'm sending you one of our newspaper accounts of the affair because it describes what happened to the lifeboat in which Black, Bolus, a Wynberg girl called Zondendyk, and myself were. When the boat capsized I managed to hang on to the side and hung and hung until the boat righted itself but it was the most ghastly few minutes I ever lived through. I remember a big dark wave washing right over me and something - an oar, I think, pressed against my throat until I thought I should choke and something else crushed my eye against the boat's edge and I saw stars and felt my eyeball must burst. My corsets were torn right off me and my legs were bruised and bleeding. Then the boat righted itself and I found myself inside. There were just two of us left, the other a fellow passenger named Dawson and his pyjamas were simply torn to rags! Our boat was quite full of water and we had lost our oars and rudder. We didn't see or hear anything of the others then and were drifting right away until the Kenilworth turned and her wash brought us rushing back. I really thought that was the very end but we did a surprising turn and instead of crashing into her we rushed along her side and crossed her stern so close that Mr Dawson was struck in the mouth and his teeth knocked out. Then we got out on the other side and that was the last we saw of the Kenilworth. It was horribly dark and we could hear the dreadful calls for help from men and women in the water but could not get near to them. Two women drifted right up to the boat and these were saved. One was the young wife of a Colonel of Marines - the other Nurse Zondendyk. I found a bucket and a scoop tied to the boat and these were used to bale out the water - Mr Dawson and I baled and baled until we were too tired to do any more but the boat felt almost respectable again so we all sat huddled together shivering and taking turns at being sea sick!

When morning dawned we made the ghastly discovery that our barrel of drinking water had been lost when the boat capsized and though there were plenty of ship's biscuits we only ate a few mouthfuls as they were such thirst provoking things. My veil was hoisted as a flag of distress and then there was nothing to do but look at the sea and wonder what fate had in store for us. I don't wonder people go mad in lifeboats, the monotony is terrible but it seemed more terrible still when a seaplane and a destroyer passed without seeing us. We had no idea where we were drifting; far away we heard the sound of guns but we only saw sea and sea and sea. Such a rough sea too, one moment we were down in a valley the next high on a wave. We had to hold on sometimes and waves would keep coming in. Take my advice dear Wrensch, and keep away from lifeboats - they are not pleasant things. There didn't seem much chance of being rescued and we didn't like the idea of dying of thirst so we had a calm discussion on the quickest way to die. I wanted Mr Dawson to promise to choke us when our thirst became unbearable but he refused. My throat was dry then and my tongue felt like a piece of leather but I found a tin of varnish - whitish watery stuff, which I tasted and felt much better. Then we made preparations for the night. We found some red flares, signals of distress, which we decided to use that night. We knew it was risky and might bring a German submarine down upon us but something had got to happen we didn't much care what. Then we sighted 'it'. 'It' was the finest destroyer that ever was built for His Majesty's Navy. It was going away from us but it saw us and it turned and came towards us and we realised we were saved. Oh, the relief, for I really didn't want to be choked by Mr Dawson. We were soon safely on board the destroyer and were simply overwhelmed with kindness. The officers told us we were the first women who had ever been on their ship. We were washed and fed and put to bed in the Officers' beds and I quite enjoyed that part of the venture. They sent a wireless message to Plymouth saying we were alive and coming, for, of course, by this time everyone supposed we were drowned. As soon as we touched Plymouth Colonel Jones rushed on board and kissed us all twice. Perhaps had he seen me hauling his wife into the lifeboat by her legs he might not have been so affectionate! And so ended the great adventure.

Love from

Bracken.

John Doran

If you can provide any additional information, please add it here.

|

Want to know more about HMS Kent?

There are:5 articles tagged HMS Kent available in our Library There are:5 articles tagged HMS Kent available in our Library  |

Those known to have served in HMS Kent during the Great War 1914-1918. - Ash Charlie. Private (d.25 May 1919)

- Munro A.. Ord.Sea. (d.25th August 1915)

The names on this list have been submitted by relatives, friends, neighbours and others who wish to remember them, if you have any names to add or any recollections or photos of those listed,

please Add a Name to this List

Records of HMS Kent from other sources.

|

|

The Wartime Memories Project is the original WW1 and WW2 commemoration website.

- 1st of September 2024 marks 25 years since the launch of the Wartime Memories Project. Thanks to everyone who has supported us over this time.

|

Want to find out more about your relative's service? Want to know what life was like during the Great War? Our

Library contains many many diary entries, personal letters and other documents, most transcribed into plain text.

|

Looking for help with Family History Research?

Please see Family History FAQ's

Please note: We are unable to provide individual research.

|

|

Can you help?

The free to access section of The Wartime Memories Project website is run by volunteers and funded by donations from our visitors.

If the information here has been helpful or you have enjoyed reaching the stories please conside making a donation, no matter how small, would be much appreciated, annually we need to raise enough funds to pay for our web hosting or this site will vanish from the web.

If you enjoy this site

please consider making a donation.

Announcements

- 26th Mar 2025

Please note we currently have a massive backlog of submitted material, our volunteers are working through this as quickly as possible and all names, stories and photos will be added to the site. If you have already submitted a story to the site and your UID reference number is higher than

265607 your submission is still in the queue, please do not resubmit.

Wanted: Digital copies of Group photographs, Scrapbooks, Autograph books, photo albums, newspaper clippings, letters, postcards and ephemera relating to the Great War. If you have any unwanted

photographs, documents or items from the First or Second World War, please do not destroy them. The Wartime Memories Project will give them a good home and ensure that they are used for educational purposes. Please get in touch for the postal address, do not sent them to our PO Box as packages are not accepted.

|

World War 1 One ww1 wwII greatwar great battalion regiment artillery

Did you know? We also have a section on World War Two. and a

Timecapsule to preserve stories from other conflicts for future generations.

|

|

|

Want to know more about HMS Kent? There are:5 items tagged HMS Kent available in our Library There are:5 items tagged HMS Kent available in our Library

These include information on officers, regimental histories, letters, diary entries, personal accounts and information about actions during the Great War.

|

|

Recomended Reading.Available at discounted prices.

|

|

|