|

|

|

Those known to have served at RAF Dishforth during the Second World War 1939-1945. - Curwain Harold William. Sgt.

- Grigg William Hamilton. Flt.Sgt.

- Grunsell Ernest Alfred Francis. Sgt. (d.27th March 1941)

- Gurmin Edward.

- Hoad MID. Peter John. Sub Lt. (d.27th Mar 1941)

- Jackson MBE, DFM.. Roy. LAC.

- James DFM.. William Birdsall. W/O (d.10th Nov 1944)

- Keen CGM, DFM.. Geoffrey Frank. Sqn Ldr.

- McCracken Lloyd Christie. FO.

- Mills Alan Kingsley. Sgt. (d.27th March 1941)

- Moloney Edward William John. Sqd.Ldr.

- Seager Kenneth Frank. P/O (d.27th March 1941)

- Watson DFC.. Dennis Arthur. P/O.

- White Reginald James. Sgt. (d.16th Jan 1942)

The names on this list have been submitted by relatives, friends, neighbours and others who wish to remember them, if you have any names to add or any recollections or photos of those listed,

please

Add a Name to this List

|

|

|

The Wartime Memories Project is the original WW1 and WW2 commemoration website.

Announcements

- 1st of September 2024 marks 25 years since the launch of the Wartime Memories Project. Thanks to everyone who has supported us over this time.

- The Wartime Memories Project has been running for 25 years. If you would like to support us, a donation, no matter how small, would be much appreciated, annually we need to raise enough funds to pay for our web hosting and admin or this site will vanish from the web.

- 19th Nov 2024 - Please note we currently have a huge backlog of submitted material, our volunteers are working through this as quickly as possible and all names, stories and photos will be added to the site. If you have already submitted a story to the site and your UID reference number is higher than

264989 your information is still in the queue, please do not resubmit, we are working through them as quickly as possible.

- Looking for help with Family History Research?

Please read our Family History FAQs

- The free to access section of The Wartime Memories Project website is run by volunteers and funded by donations from our visitors. If the information here has been helpful or you have enjoyed reaching the stories please conside making a donation, no matter how small, would be much appreciated, annually we need to raise enough funds to pay for our web hosting or this site will vanish from the web.

If you enjoy this site

please consider making a donation.

Want to find out more about your relative's service? Want to know what life was like during the War? Our

Library contains an ever growing number diary entries, personal letters and other documents, most transcribed into plain text. |

|

Wanted: Digital copies of Group photographs, Scrapbooks, Autograph books, photo albums, newspaper clippings, letters, postcards and ephemera relating to WW2. We would like to obtain digital copies of any documents or photographs relating to WW2 you may have at home. If you have any unwanted

photographs, documents or items from the First or Second World War, please do not destroy them.

The Wartime Memories Project will give them a good home and ensure that they are used for educational purposes. Please get in touch for the postal address, do not sent them to our PO Box as packages are not accepted.

World War 1 One ww1 wwII second 1939 1945 battalion

Did you know? We also have a section on The Great War. and a

Timecapsule to preserve stories from other conflicts for future generations.

|

|

Want to know more about RAF Dishforth? There are:35 items tagged RAF Dishforth available in our Library There are:35 items tagged RAF Dishforth available in our Library

These include information on officers, regimental histories, letters, diary entries, personal accounts and information about actions during the Second World War. |

|

Sqn Ldr. Geoffrey Frank "Chuffo" Keen CGM, DFM. 51 Sqn.  Geoffrey Frank Keen was born in Chesham, Buckinghamshire, on 26th March 1916, the youngest of five children, with a brother Jack and three sisters Doris, Gwen and Mary, born to Minnie and Percy Keen. He was never to meet his father, he was killed in action near Messines Ridge in Flanders on 4th June 1917.

At Dr. Challoners Grammar School, Amersham, he was an enthusiastic sportsman and represented the school at both cricket and football. On leaving school he served an apprenticeship in printing, working for the company which produced the local newspaper.

His enthusiasm for sport continued after he left school and became an important part of his life. He and his brother Jack both played for the Town Club, Chesham United, and Geoffrey had trials for both Stoke City and Queens Park Rangers.

On the outbreak of war the two brothers decided to join the RAF and in October 1940 Geoffrey was posted to Yatesbury for basic training then on to Penrhos for Bombing and Gunnery School and finally to Abingdon OTU for wireless training before the finished article was posted to his first operational base as wireless operator/air gunner Sergeant Keen at Dishforth and 51 Squadron, equipped with Whitleys. His log book entries include:

1941, Kiel-could not reach target,- bombed Boulogne Docks instead, Bremen, Mannheim, Hanover, Kiel-'pranged' on drome, Cologne, Dortmund, Duisburg. Wihelmshaven, Brest, Dunkirk, Emden, Frankfurt-baled out East Dereham, Berlin, Stuttgart, Nuremberg, 1942, Cologne(1000 bombers), Essen(1000 bombers), Dusseldorf.

He completed his first tour (30 ops) in November 1941 and was posted to Abingdon No.10 OTU in December. In January 1942 he was cited in the London Gazette as follows:

Distinguished Flying Medal (D.F.M.) London Gazette 30.1.42. Sergeant, No. 51 Squadron, the recommendation states:

'During the many sorties in which this wireless operator has participated, some of which have been at extreme range, he has displayed high qualities of courage and determination. His technical skill is of a high order and on one occasion, after a raid on Stuttgart, his steadiness in obtaining wireless aid was solely responsible for the return of his aircraft after bearings had been completely lost.'

Flight Sergeant Geoffrey Keen became a founder member of 427 Squadron as the wireless operator to Wing Commander Dudley Burnside when he became the squadrons C/O and it was on only their seventh operation together that the crews abilities were tested to the limit and for which four of them were decorated, including Geoffrey as cited below:

Conspicuous Gallantry Medal (C.G.M.) London Gazette 23. 4. 43 Flight Sergeant D.F.M., No.427 (Lion) Squadron, Royal Canadian Air Force.

On the night of 12th March 1943, this airman was the wireless operator of an aircraft detailed to attack Essen. Whilst over the target area the aircraft was hit by heavy anti-aircraft fire. The navigator was killed instantaneously. Flight Sergeant Keen, who was in the astro-dome, had his right foot blown off and received cuts to both legs. Disregarding his wounds, Flight Sergeant Keen regained his seat in the wireless cabin. For over two hours he laboured to repair the damaged apparatus. He could not speak to other members of the crew owing to damage to the inter-communication apparatus. Another airman spoke to him, however, on at least a dozen occasions and found him still conscious and working at his self-imposed task of directing the manipulation of various installations. He also offered assistance in navigating the aircraft and actually managed to drag himself on two occasions to the navigator's compartment to obtain essential information necessary for the aircraft's safe return. His courage and fortitude in such circumstances were of the highest order

The recommendation states: 'I consider this N.C.O.'s superb display of courage and devotion to duty whilst seriously wounded fully merits the award of the Victoria Cross' (Wing Commander D. H. Burnside, Commanding Officer, RCAF Station, Middleton St. George).

'This case is considered to be an outstanding example of coolness and tenacity of purpose on the part of this N.C.O. when seriously wounded, and demanding courage of the highest order-an award of the Victoria Cross is recommended (Air Officer Commanding 6 Group, Air Vice Marshall G.E. Brookes CB OBE )

`As was only fitting, the very fine display of courage and determination shown by all members of the crew was subsequently recognised by awards. Burnside received a Bar to his DFC, Hayhurst and Ross the DFC, and Keen, who already had the DFM, the Conspicuous Gallantry Medal.' (RCAF Overseas 1944)

As a result of his wounds part of his right foot was amputated but after a period of three months convalescence he returned to the squadron where he remained for the duration of the war, finishing as Squadron Leader responsible for training of Group 6 wireless operators.

Upon returning to civilian life he trained as a teacher before marrying Jose Barnes, the girl he met after a visit to the cinema in Oxford while training at Abingdon. In 1948 they moved to his home town Chesham, where he was to become Assistant Head and eventually Headmaster of the local village school of St Leonards in Buckinghamshire.

Always a keen sportsman and in spite of the lack of half a foot he continued to play football and cricket not only at club level for Chesham United FC and Chesham CC but also at county level winning several winners medals in the process. When his playing days were over he took up umpiring, golf and bowls. Heaven knows how he found the time to look after the garden.

|

W/O William Birdsall James DFM. 51 Squadron (d.10th Nov 1944)     This is Bill James's story, it is factual drawing on eyewitness accounts.

Dusk on 18th August 1941. At R.A.F. Dishforth in Yorkshire, Squadron Leader John Bouwens D.F.C. is leading a line of Whitley Bombers to the grass runway. The target is the German city of Cologne, an industrial and route centre occupying a key point in the German rail network. Bouwens is an experienced pilot and is leading a force of twelve bombers from 51 Squadron at a point in the war where losses are mounting. This is to be a fateful night for many of the aircrew.

With the distinctive throaty roar of the Merlin engines reverberating across the darkening landscape, Bouwens lifts his aircraft with its load of bombs and incendiaries clear of the ground and climbs away towards the target. A few minutes behind him is Whitley Bomber “Q for Queenie”, at the controls is Sergeant Bill James, a Yorkshireman from Leeds and at 20 already an experienced pilot.

The aircraft crosses the coast still climbing to the cruising level of around 11,000 feet, it is an almost moonless night and they are spared the freezing conditions so often encountered. Bill’s navigator, Pilot Officer Derek Roberts, settles down at his navigation table and checks his chart. There are no fancy electronic aids at this stage of the war, just a map, compass, slide rule and protractor. He will be navigating using time and distance with the wind vector figured in. Over a blacked out continent and little moonlight (which brings it’s own problems anyway) there isn’t much scope for map reading.

Cologne at least is easy to recognise if there is some light, the distinctive bend in the Rhine and the cathedral next to the railway yards. It is these railway yards they are to attack. The bomber drones on through the night, the other aircraft on the raid are invisible, formation flying at night is dangerous at the best of times but without navigation lights it would be suicidal. Each bomber is effectively on it’s own.

William Birdsall James was the only son of a schoolteacher and had attended West Leeds Boys High School, he had also visited Germany with his father shortly before the war. The preparations for war he saw there shocked him and encouraged him to join the R.A.F. By August 1941 at the age of just twenty he was now one of the squadron’s best pilots, greatly trusted by his crew. Over Frankfurt on 22nd July in a violent thunderstorm a “Flak” shell exploded under the bomber’s wing turning the aircraft onto its back. Not something the lumbering Whitley was designed for! Bill managed to right the aircraft and bring it under control but not before losing 8,000 feet. It was by flying like this that he gained the confidence and respect of his crew.

At about 2 AM “Queenie” arrives over the target area and begins the bombing run. The weather is good but this just helps the German gunners, heavy flak bursts around them as searchlights probe the sky. Despite this the aircraft makes it through the storm unscathed and drops it’s load of bombs. At the end of the run Bill turns steeply away from the target to shake off the searchlights and settles onto the new heading given to him by Derek for the return journey.

This return journey is not necessarily the easy bit, aircraft may have unknown damage from flak over the target, there are the usual navigational hazards, fatigue, the possibility of fog over the home airfield and of course night fighters. It was a preferred time for opening thermos flasks though, drinking early in the flight might mean using the aircraft’s primitive toilet facilities!

Derek sits down at his navigating table to open his flask of coffee when the interior of the aircraft suddenly lights up with the intense illumination of a searchlight. They are not out of the woods yet and have encountered an unexpected searchlight battery. As there is no smoke without fire, so it is with searchlights and guns. Cursing loudly Bill throws the aircraft into a series of violent manoeuvres in an attempt to shake off the light. Flak shells burst around them but despite Bill’s best efforts the searchlight remains steadfastly on target. Inevitably the flak closes in as the gunners correct their point of aim and a violent explosion shakes the bomber as it takes a direct hit.

Acrid smoke fills the cabin and the aircraft dives earthwards, Bill with shrapnel wounds in his legs struggles to control it but realising a crash is inevitable he coolly gives the order to bale out. His crew hesitate, reluctant to leave the security of the bomber and somehow believing “Queenie” will get them home as she always does. A curt, authoritative repetition of the order dismisses any such beliefs and they hastened to their parachutes. The tail gunner, Sgt Janus, one of two Canadians in the crew, drops out through his turret but the second pilot, Don Switzer struggles to get the front hatch open. With the aircraft screaming earthwards Derek Roberts assists him and soon Switzer’s lanky frame is through the hatch and plummeting into the darkness. Derek is right behind him, a quick check of his harness and through the hatch. Sgt Lowe, the wireless operator, has more to worry about. His parachute has been shredded by shrapnel and is clearly useless, he resolves therefore to stay in the aircraft.

Bill is now in a dilemma, the bomber was careering earthwards and Lowe can’t possibly fly it. He takes his own parachute and thrusts it at Lowe ordering him to jump. In any aircraft the pilot is in charge and in a situation like this his orders must be followed immediately, at 2000 feet Lowe jumps into the black void of the forward hatch. Bill despite his leg wounds manages to bring the aircraft to earth in pitch darkness, so badly damaged it cannot remain airborne, landing in an unlit field. It is another amazing piece of flying but also his last.

Struggling clear of the wreckage, Bill had the presence of mind to set fire to the aircraft to prevent the enemy from making use of it. He was then taken prisoner by the Luftwaffe, who probably treated him well, as the others were that day, but the future was bleak. He was taken to hospital to be treated for his leg injuries and from there went into the P.O.W. system.

Bill James went to Stalag Luft 3, from there he wrote home praising the coolness and discipline of his crew. From reports sent back home by them he was awarded the Distinguished Flying Medal in July 1942, cheers rang out in the camp when the news arrived over their secret radio. Soon afterwards Bill developed tuberculosis, probably aggravated by poor diet and overcrowding in the camp.

He was eventually repatriated via the Red Cross, but died about two weeks later. I have been told he held on to life long enough to return to England as he did not want to die in Germany. Bill was an only child, his parents kept in touch with his crew after the war but must have been heartbroken, as were many.

John Bouwens didn’t make it either, he was killed the following year in the Far East and four out of the twelve bombers that night failed to return. Bill James is now remembered at his old school, I have the gold pocket-watch he would have inherited from his father and been given James as my middle name.

|

FO. Lloyd Christie "Little Mac" McCracken 426 Squadron     I enlisted in the Royal Canadian Air Force June 10, 1940 and was discharged July 30, 1945. I entered as Aircraftsman Second Class and left as a Flying Officer. I was taken on Active Force June 11, 1940 and arrived overseas on November 5, 1942.

The following tale is a personal memory of my days in the Royal Canadian Air Force. It was a time of new experiences, sometimes very exciting and at other times very boring. I have been able to refresh my memory with my log book, the logs and charts of our operational trips and my letters home. I was able, in 1992 to attend a reunion in Trenton, Ontario, which helped renew memories and create a desire to record my history fifty years later. In addition I have consulted the 426 Squadron History written by Captain Ray Jacobson. I have provided commentary from authorities whenever I thought they might help clarify certain terms and concepts. I take great pride in having been a member of the Royal Canadian Air Force.

Signing Up

I cannot now remember exactly how I felt on that day, September 10, when we learned that Canada was at war. However, I can recall everyone rushing around talking of food shortages. I had taken a Motor Mechanics course in Fredericton and was employed by Herb Swan, in Harvey Station from September 1 to October 8, 1939. They were building a road and a lot of heavy trucks needed their motors overhauled, so I worked until the end of the rush period. I was then employed by Harry McCracken, who, living in Welsford at the time, managed the Service Station in Fredericton Junction, at which I became an attendant from October 10 to October 31. It then closed for the winter. During this winter period I became a cookee for Harry Brawn in back of Tracy, near the beginning of Meransey Brook. I was beginning to notice that fellows in uniforms received more attention from girls than the average guy. This made the Air Force look quite appealing, so on the 16th of April, 1940, at the age of seventeen, I completed forms on my personal history, education, parents, and work experiences for W.G. Cook, Flying Officer.

On June 10th, 1940, I boarded the train for Moncton, New Brunswick Canada; really my first time away from home on my own. After arriving,I remember asking at the post office where you go to enlist. The building was handy and there were other fellows signing up as well. I was told I needed a letter of recommendation and the only person I knew in Moncton was Doug Ball. He was working at the airport, so I called a taxi and went and looked him up. He seemed very busy, gave me his address and asked me to drop by his home later and pick up the letter. I did that and was quite pleased at what he had done for me. More forms were filled out including a Medical Form indicating I had a scar on my leg (from sharpening a knife as a young fellow. That knife was so sharp you could split a hair off a donkey.) It also mentioned a fractured nose( when I was about ten, I was playing ball and was batting. I hit the ball, then the ball hit my nose. It bled and bled but I didn’t go to a doctor). The medical form also records my height to be 5 ft. 6 1/2 in., and weighing 126 pounds. I made out a will, leaving everything to my mother. The next day we were off to Ottawa. Mother had thought I would be home before leaving. However, she didn’t hear from me until two weeks later when she received my letter. She didn’t know what had happened to me and I think she was quite sore at me for not writing earlier.

We traveled to Ottawa by train. We were young and green but we did know that we were supposed to salute officers. We got off the train and saw the Parliament Buildings. On going into a hotel, we noticed a man standing in a uniform with a hat, so we saluted, thinking this fellow was an officer. He never responded, except to give us a funny look - this was our introduction to a doorman.

Initial Training School.

We then took a bus to Rocliffe Air Station to report for I.T.S. (Initial Training School).

On the first morning names were called out to report to various messes. Upon arrival you were put to work. Some reported to Officer’s Quarters and became cleaners. Others reported to various buildings to wash and wax floors. I worked in the kitchen slicing bacon, setting tables, washing dishes - I enjoyed the dishwasher, and peeling potatoes. They had large bins that would hold 100 lbs. of potatoes. It went around and around, and as it did it took off the skins. I thought that was pretty slick!

The purpose of this was to experience service life while waiting for space at Initial Training School, (I.T.S.). While here, we also learned how to march, went on parade, and attended church. This period lasted for two or three months.

My R.C.A.F. number was R64681, which I have remembered all my life, even after I became an officer and was issued a new number J96264. Barrack life was quite different from what we were used to. However, we did have a lot of fun horsing around. After my first visit to a wet canteen I was feeling pretty good and I swung at a guy to scare him and hit the wall above his head. My fist went through the wall and I quickly covered the hole with an Air Force crest I had bought. It had been pinned on the wall so I just moved it over the hole. I didn’t want anyone to find out, and perhaps get in trouble.

We received all of our inoculations here. We lined up in the fields and stood so long waiting our turn that some guys fainted just from the thought of all those needles. Here we were supposed to sign up and go anywhere we were called. It was quite a treat to get out of the Junction.

One day a sergeant in the kitchen took some of us through Ottawa in a car with a rumble seat and the top down. We crossed the bridge to Hull. In the evenings we had a ten o’clock curfew. Another fellow and I went to the theater where there were a lot of older people and we had a great time. We laughed so hard and hated to leave. We were really enjoying ourselves. We left at ten and were late getting in but no one paid any attention to our arrival. It was a great time here and I especially enjoyed the marching.

#1 Wireless School - Montreal.

Next I was transferred to # 1 Wireless School on Queen Mary Road outside the center of Montreal. I traveled by train and became an AC1 (Air Craftsman 1st Class) on the 11th of September, 1940. The only work we did here was guard duty. I was given a rifle and was told to stand in a box. This was a picnic. We were waiting to get on course. One civilian came along and just for fun,I said "Halt!" The civilian frowned, looked at me and said "What’s your problem?" He went on in and complained to a sergeant. I was called in and told to go easy on civilians. If we stayed out too late we ended up picking dandelions. But that was all right too. We were given a stick with a V shape on the end that picked them. Well, we’d go along, picking away and then when no one was looking, we would visit with our female neighbours near the back fence. They were maids keeping children. Yes, we had a great time there.

We ate well while at #1 Wireless Training School. On the ends of the tables were big jugs of milk, of which we were always running out, and the kitchen help had to keep running in and refilling the jugs. After a while he just brought out two five gallon jugs, placed one on each end of the table, and told us to help ourselves. One fellow thought he recognized my last name. He asked me if I was related to Crowley McCracken from Ontario. I didn’t really know but I guessed I must have been. Crowley had the contract to feed all of us in the #1 Wireless School. We were just placed here as a holding unit.

#3 Training Command - Montreal.

I was next transferred to #3 Training Command, St. James Street in Montreal. Here we took a course in Shorthand and it didn’t take long to realize that some of us weren’t too good at that. I worked in the offices for the central registry where my job was to open and sort the mail for the officers in the electrical and plumbing building. They were large buildings with three or four floors of offices. Once I got in trouble for opening mail marked "Confidential".

Here I rented a room on Lagouchitere Street, along with another fellow, Gordon Gilbert whom I found in the #3 Training Command. Opposite us, men were beginning to dig the foundation for Montreal’s underground railway station. For breakfast we would have cornflakes and milk, and for lunch and supper we would go to a restaurant. You could get a good feed of liver and onions for 70 cents and they sure did a good job. This place did a big business to truck drivers as well. I ate here a lot. Another favorite spot was Mother Martins. This tavern was handy and was operated by an older lady who was interested in all of us young fellows and how we were doing.

I was approached and asked to run the canteen. I had to take money from here to a bank in Westmount. I was pleased they trusted me with this. I sold sweatshirts with the Air Force crest on them. We purchased them for 35 cents and sold them for $1.50. I sold watches and charged $10.00 less than other stores and still made a great profit.

Sometimes we were asked to be Special Police in the evenings; not often, just the odd night when the boys were rowdy. We wore a band on our arm, with S. P. on it, for Special Police, and occasionally would take it off and go to the movies. It was a great life!

While at the canteen I was on a Softball team, and occasionally enjoyed hockey games, which were free to aircrew. I bought a bike for my youngest sister Ethel, and put it together, then took it apart and put it in a crate to send it down on the train. Usually they are sent assembled. Father and my brother Larrie had an awful time getting it home and putting it together. The country was so busy making war materials, a bike was hard to get.

I was acting out and cut my finger on a bottle and was taken to the Royal Victoria Hospital and received stitches. From here I went back to #3 Training Command doing clerical work.

While living at home, my sister, Helen, had Scarlet Fever and we had all been quarantined. Therefore, I believed I had had it too. In Montreal I was hospitalized and they were uncertain as to what I had. I was very sick yet told to help myself to the fluids in the refrigerator. When I did get up to get some there wouldn’t be any there. I went days without fluid - they tried to starve me. The doctor came, saw me, and sent me by Air Force Ambulance to Montreal General. In the ambulance a boil had broken in my mouth - it tasted awful! I arrived and a doctor checked me over and I got settled in. They still wondered what I had and thought it might be Scarlet Fever. I was then taken to Alexandra Hospital, and placed in a glass cubicle. It was the only way they could quarantine me. I lay awake at night and slept all day. I couldn’t eat and was there over a week. When I broke out in a rash the doctor was almost certain that it was scarlet fever. I was put in a ward for a while, and then moved upstairs. Helen was working at a TB Hospital in St. Agathe and she would occasionally phone and come to visit. The doctor reported that on October 31, I developed strawberry tongue and was now positive that it was scarlet fever. After November 1st, I made a rapid recovery and continued to do well until my discharge, November 20. My personal address was 4450 Sherbrooke St. W. Montreal, August 2, 1941.

I also had tonsillitis and was admitted to the hospital at the Wireless Training School for three days. They were removed at the Royal Victoria Hospital and I was there a further four days, then on to St. Anne’s Military Hospital for six days. I soon became bored here and upon receiving a letter from mother, learned that my brothers Charlie and Harvey enlisted in the army and had been transferred overseas. Probably they were in Halifax waiting to go. It was a short time later I decided to remuster in the air crew and go overseas.

It was decided June 24th, 1942, that I was "good material for an air gunner, a good marksman, keen to fly, wanted to be an air gunner, some boxing, fighter type, with plenty of ambition". These comments were recorded by Flight Officer J.O. Laffoley. I had been a clerk 1 so I spoke to my officer, Laffoley and he looked into it. I had trouble passing the medical exam due to breathing problems. After treating the problem they then made arrangements for the next gunnery course which began in Mount Jolie, Quebec.

I planned to go home for Christmas, had $400 saved, but at the last moment wasn’t allowed to leave, so bought gifts at Morgans, a big department store of four or five stories. I remember buying a 5 pound box of the best chocolates they had. I can’t remember anything else I bought but I did have a good time buying and shipping the presents home.

Number 9 Bombing and Gunnery School - Mont Jolie

My next transfer was to Number 9 Bombing and Gunnery School in Mount Jolie on the 19th of July, 1942.

I was now a Leading Aircraftsman with an increase in pay. At the beginning of this course we were entitled to wear a white flash on the front of our forage cap signifying that we were air crew under training. This was an eight week course beginning on July 27, and ending on September 10th. At the end we were to receive our wings and promotion to rank of sergeant. Life was looking up.

During the gunnery course we did a lot of skeet shooting which consisted of shooting clay pigeons out of the air from different angles. I became pretty good at this. In the report on skeet shooting my officers remarks report "average". Once, while home on leave, I was able to show off a little while hunting with my brother. I shot three Gorbies(Grey Jays) on the wing, one after another.

We had plenty of flying experience as well. We flew in the old Fairey Battle planes which were used in World War I. These had a single engine and we would drop smoke bombs on the St. Lawrence River, circle around, and then shoot at them. One fellow dived too low and a wing went under water. It then pulled him down into the water but he was able to get out of the plane and swim to shore.

My most memorable and nerve racking flight during training was when our pilot put down the landing gear and only one wheel came down. The Commanding Officer (C.O.) in the tower told the pilot to put our other wheel up and come in on the plane’s belly. We were told to prepare for a crash landing. We did this and it caused us to stop faster but never did much damage.

I was given a 30 day leave so went home and worked on the farm with my brothers Larrie and Arthur and told stories. I remember telling them "if I ever get hit, I hope it’s not in the stomach". I wanted a quick ending.

I returned to Mount Jolie and at the end of the course received my wings and a promotion to the rank of sergeant. My flying log tells me I had accumulated 16 hours flying time and my marks were 81%. I was awarded an Air Gunner Badge, 1942. I had my sergeant stripes and wings sewn on and removed the white flash from my hat. We knew that approximately the top third of the class would be commissioned and I learned that I had a chance for a commission but I would need $50. This posed an immediate problem as I didn’t have the funds. I wrote home asking my brother Larrie if he could loan me the cash. He was unable to help out so I ended up turning down the commission. I was given about one month leave and went home to visit my family before leaving Canada for overseas.

We were kept seven days in a holding unit for people waiting for the ship to England. This was really a sorry place. Our beds were loose straw with a blanket. The person who slept there before me had the crabs, (body lice) and I found out they were contagious. We had to stay right there the entire time.

Our ocean liner, the Queen Mary, one of the most luxurious ships ever built, was more than 1,000 feet long and would cross the Atlantic Ocean in just over five days. The rooms were jam packed with men. We were crowded in double or triple tiered steel beds closely packed with duffel bags. I shared a cabin, meant to accommodate two, with five other men.

I was on the ship writing letters home about a week before it left shore. We went to the mess hall for our meals and were served on white linen. It was beautiful. We fed like kings on the Queen Mary. I remember enjoying salmon with a twist of lemon. The weather was good and the ship was so large that no one experienced sea sickness. We spent most of our time eating, sleeping and visiting a few guys we knew. There wasn’t enough room to play card games.

Before leaving, men were taking bathroom fixtures and the like. It was all so fancy and very sad to see them do this. Some of us had bought silk stockings in Canada, for we had heard they were very rare in England. We thought we might give them to some of the girls over there. However, someone on the boat had taken my silk stockings and a new pair of air force gloves.

England.

On November 1, 1942, we docked in Greenwich, Scotland. We stayed on the boat until we got a train. It took quite a while to get the boat unloaded, as there were quite a few train loads of us. The next day I boarded a train, the "Flying Scotsman", to Bournemouth. They fed us biscuits that were as hard as bullets. The trip to Bournemouth took about a day.

In Bournemouth we were billeted in a large room in a Hall. Upon arrival, November 5, 1942, it was necessary to check with the medical officer. Bournemouth was a lovely resort town and the weather was beautiful! The whole town was a holding unit for Canadian Airmen. There was a big dining room near the beaches which served as a mess hall for NCOs,(Non Commissioned Officers). There were acres and acres of lawns and flowers, as well as water fountains, peacocks, big trees, little paths and bridges to walk on. The beach, which was seven miles long had the finest sand you ever saw. The Germans had machine gunned a group of swimmers there earlier in the war. We had little to do but enjoy ourselves while we awaited posting. The city offered plenty of entertainment; pubs, cinemas, and a music hall. From here I was posted to Instructional Training (ITU) in Wellsbourne, Warwickshire.

Instructional Training Unit - Wellsbourne.

The countryside was beautiful as I took the train to Wellsbourne. I was impressed with the beauty of the brooks, bridges and the vines growing around and over so much. Upon arrival, another class ahead of us were in the midst of a course, so we had a fair amount of leisure time on our hands. Meanwhile, we walked around, enjoyed the country side and the girls.

I was given seven days leave from the 11th of December to the 17th. and had been invited to spend Christmas with friends but chose instead to stay on the base. Between the 29th of January and the 10th of February, 1943, I enjoyed another 13 days leave. Quite often the airmen would visit London or take bicycle rides through Stratford-on-Avon. Once my course began it did not involve flying, but rather was instructional training held in classrooms. From here I was transferred to Operational Training (OTU) in Leamington.

Operational Training Unit - Leamington.

We came from Canada, just young fellows - 18 and 19 years old flying bombers and fighters. The young English boys couldn’t get over that! In England you had to be 21 to get a driver’s licence. They couldn’t even drive a car. They were allowed to wear a uniform, but not fly a plane. I think they later lowered the age. Upon arrival October 13, 1942, we were assigned to Quonset huts. The hut had a coal stove in each end and lots of beds. The first morning we all reported to a large briefing room to be addressed by the Commanding Officer (C. O.). Among us were pilots, navigators, bomb aimers, wireless operators and gunners. The C.O. advised us we would spend most of the first week in ground school and would have some free time. The big question now was who do you crew up with, and how do you go about crewing up? Usually the pilot chose the navigator and from there on they would choose their crew.

Eventually, our crew consisted of Stanley Gaunt, a pilot from Rhode Island, U.S.A.; McCormick, a navigator from Alaska; Bomb Aimer, Lloyd Fadden from Seattle, Washington; and our wireless operator, Green from England. Some were given nicknames. McCormick, being married, seemed much older than the rest of us. He was a very quiet guy and kept to himself. We called him "Big Mac" and I was known as "Little Mac". Stanley was just called Stan. He was a really nice guy and I thought the world of him. Fadden was called "Whitie" because he had naturally white hair. He was a character, always getting into fights and trouble. He would get nasty and sassy with too many drinks. In ground school the crew would start learning about the Wellington aircraft (Wimpies) that we would be using for training.

Near the end of our tour we were in a hurry to become operational. We did cross-countries, some low flying, air flying, and a height test. We did some ground and flying training, then a load test, night flying and were then ready for operations.

Our first bombing raid was at an altitude new to us, twenty thousand feet. This meant we would be using oxygen for the first time. Some people have said they found this mask somewhat unpleasant. I was just glad I had it! We did a lot of flying and shooting from the air. Some of the fellows shot at some sheep and got in trouble for that. Before finishing our flying we had one hair raising experience. We had been flying around, quite low at this point. The pilot was busy looking for girls and didn’t see a three inch thick cable until he was right in front of it. He quickly decided to go under it and in so doing went so low the wind from the plane blew the grass right over. We thought that was pretty close and tried to pay closer attention after that.

My boots were beginning to give me a problem so I took the bus to the store to see what could be done about a new pair. The Englishman at the desk looked at them and concluded they were still in pretty good shape, and therefore decided he wouldn’t give me a new pair. I responded with "I’ll get them!" So of I went to the office sergeant and asked him if I could see the C.O. He told me I couldn’t see the C.O. and asked me what my trouble was. I explained my situation and he immediately picked up the phone and called the clerk at the store and told him to give me the boots. I suppose the clerk never figured I’d go to anyone and was just taking the opportunity to show his authority. Well I was pleased as I was handed the boots right away.

During one of our test flights the arrival back in England was not so good. Once one wheel came down and one didn’t. We landed and just spun around in circles, bent the propeller all up and broke off one wing. Imagine being in the tail end of a plane spinning round and round. You really felt it back there. Fire trucks, ambulances, staff and the C.O. all came out to the runway. We were alright but pretty shook up - it happened so fast.

I had entered O.T.U. on the 13th of October, 1942 and left on the 10th of February, 1943. My total day time flying hours were 11, and the total night time flying hours were 20. The remarks of my C.O. are as follows: Keen, average gunner. The deficiency in flying times is due to the fact that the previous air gunner was taken off training and Sgt. McCracken subsisted in the crew. The assessment placed me as an air gunner 5.

426 Squadron - Bomber Command, Dishforth.

On February 1st, 1943, I was posted to 426 Squadron, Canada’s’ Bomber Squadron, Group 6. We were given a special meal of ham and eggs before we left for each bombing raid and upon arrival home another great meal.

I could only just get my goon suit on over the top of my flight clothes. What a job to get into the turret, especially with the parachute pack clipped to the upper left-hand side.

My first operational of night time bombing occurred March 3, 1943. I had to ride in the top turret and observe the action. The sky was really lit up! This was definitely the most frightening time for me. I couldn’t get over how the pilot could fly the plane right in the midst of it all. You could see all the fire and fighting two hours before you reached it and yet you’d swear you were right over it all along. You couldn’t turn back until you had dropped your bombs. And all that time you just sat and watched what you were flying into.

On one occasion we were over our target and the air was heavy with flak. We saw a great big Halifax bomber coming right at us. I gave a yell. The pilot dipped the plane down and he went right over our head. That was close. On another sortie, Navigator McCormick wasn’t getting oxygen and became confused. We found ourselves flying around, apparently lost for a bit. We saw some fire below so let our bombs go. As a bomb is dropped a camera on the plane takes a picture, thereby telling us if we hit our target, or how close we came. We eventually learned we had shot at a burning haystack. The Germans must have seen us flying around so set fire to one of their haystacks.

Records of the 426 Squadron report a plane being heavily shot up. Our aircraft was the one with over a hundred flak holes. The flak hit the back of my flying jacket, leaving in it a hole about a foot long. It just missed my backbone and severed my intercom with the pilot. This was a close call. If the flak had hit an inch closer, it would have cut my backbone. It virtually nailed my flight suit to the steel door behind me, as my back had been right up against it, later forcing them to cut the steel door to free my jacket. With the intercom out, the crew was worried about me. I could hear them but they couldn’t hear me. I could hear Fadden say, "Little Mac must have got it". Then, speaking to me, they said, "If you can hear me, press your button". There was a button I could push that would cause a light to come on in the cockpit. I did this and the button lit up. Fadden came down to check on me and then reported back to the others. We made an emergency landing in southern England, off the White Cliffs of Dover. We came in for a crash landing with our hydraulics shot up and no brakes. There were large banks of sand across the runway to help us stop. The plane was sent to the factory for major repairs. I have no idea how I came out of there unscathed.

Once we landed, a girl was asked to drive us to Dishforth, which took all day. She was a great girl for when we stopped to visit a pub along the way she loaned us some money. When I arrived in Dishforth I was told my brother Charlie had been to see me, and that he was in the area awaiting my arrival. He had been told I was out on a bombing raid and that I hadn’t returned. They did tell him I had landed in southern England. It was good to see him again.

After bombing Bochum one night and on our trip back our gas was reading empty and when we called in to land we were told to go to another airport. Trying to find a place to land when you are running very low on fuel can be your biggest problem. Quite often a lot of planes would be returning at the same time and all would be very low on fuel. This night the pilot said he couldn’t go anywhere, he had been reading empty so long. They turned all the lights on and we had a safe landing. This was quite nerve racking, low on fuel and trying to find a place to land.

Our squadron returned to the Battle of the Ruhr to attack Dortmund May 23. This was my last sortie - I never returned. An interesting event - before this last bombing raid I had a funny (peculiar) feeling that something was going to go wrong. I cleaned out my locker and gave special chocolates to one of the girls just down from us. It was as though I knew I would not return. As I was leaving the mess hall I told the pilot "I’ll see you in Dulag Luft."

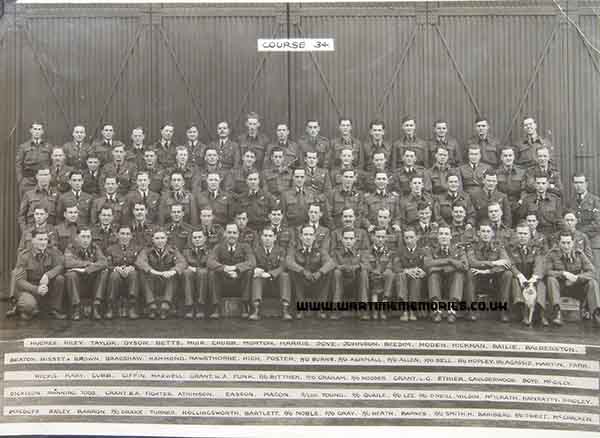

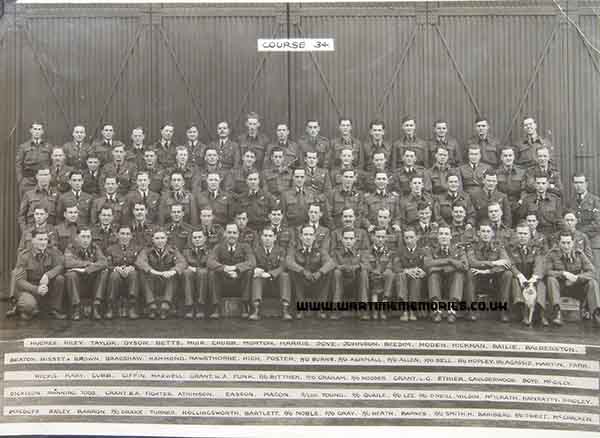

A friend, Bailey and myself signed our money over to another fellow who wasn’t flying that night, as was the custom before each air raid. Neither of us returned. Bailey’s plane was coned in search lights. The pilot took a fast nose dive to escape the lights and then tried to pull up quickly to evade the enemy. Something must have gone wrong, for the pilot gave the order to bail out. When Bailey jumped he was too close to the ground and his parachute never had a chance to open. I have a picture of him. He is located in the first row of my photo in Operational Training Unit. He was engaged so I visited southern England to speak to his fiancee regarding his death. A difficult time but I was glad to do this for them.

At the Dortmund raid, our crew, skippered by Sgt. Stanley Gaunt, had a very difficult trip. Our plane was coned by search lights and we received repeated hits by anti-aircraft guns, taking out our hydraulics, intercom and starting a fire. Whitey Fadden and I received the order to bale out. Before the rest of the crew jumped, the fire went out and Gaunt decided to try to fly the plane home. He made it and received the Distinguished Flying Medal for his heroics.

My next scheduled operation was to be in a Lancaster. However, I never made it back. The last I remember was a big gust of wind hitting me as I turned the turret around crossways, leaned backwards and fell out. My intercom cord was hooked around something and snapped in two giving me quite a jerk and knocking me unconscious. Luckily, my hand was on the rip cord and the jerk snapped my hand down opening the chute. I wasn’t conscious to bend my knees and break my fall, so all my weight came down on one leg. It was twisted pretty badly.

Prisoner of War.

It was early morning and still dark when I came to, looked up, and saw open sky and stars above me. I thought I was in PMQs back in England and that we must have been bombed and our roof blown off. I fell asleep and awoke the second time, now daylight, with my parachute spread all around me and discovered I had landed in the end of a turnip patch, close to the farm buildings. Hitting the ground with terrific force, I lost a boot. I couldn’t walk so I crawled on my hands and knees and tried to bury my parachute in a pond. This was impossible so I left it, crawled up to the barn and sat in the sun until someone came around. Finally a young fellow came from the house to feed the cattle. I called twice and when he saw me he went back into the house. The father came out and took me in, sat me at the table and gave me some bread. He couldn’t have been friendlier. I offered them my escape kit but they refused. They could get in trouble if the Germans found they had received anything from us. They asked me where my parachute was, then the old fellow took off on a bicycle and was gone for about two hours. He arrived back later with a guard.

The German guard looked at me and in English said, "For you, the war is over." This seemed to be the only English the German guards could say, for each of the prisoners got the same greeting. This later became a joke among the POWs in prison camp.

We progressed from interrogation to a holding unit and then to a Stalag or prison. I was taken just outside Dusseldorf to a farm house which had an office. I was held here for a couple of days in a building made of concrete building blocks. Inside was a bunk, a window and a guard. An older guard and a girl from the office came and stood in my doorway smiling. I must have appeared pretty down for I believe they were trying to get me to smile. Finally I did and they returned to the office.

From here I was taken to an office in Dusseldorf with seven or eight Special Service men. These fellows had grown up in the States and could pass without any trouble as American or Canadian airmen. They spoke better English than most of us. They looked like they were ready to slap me in the head but I just sat there giving my name, rank and number. I was afraid but stubborn. I remember being given three small potatoes that had been boiled with the skins on. The guard took the largest potato.

I was taken to a hospital because of my bad leg and spent about a month in a room in the basement. They didn’t want me on a regular floor with the rest of their patients. They found I had strained ligaments. Being the only prisoner there, a few of the nurses and staff came down and looked at me as though I were a pet monkey. Someone took my wrist watch and I kept complaining and finally, after a week or so, they brought it back to me.

From here I was placed on a street car carrying civilians and, accompanied by a guard, traveled up the Rhine River from Dusseldorf to Dulag Luft in Frankfurt. Scenery was beautiful. I remember grapes growing on a nearly thirty foot high bank. Half way there we stopped at a station and a woman brought me a bowl of rice - no milk or sugar, just a large bowl of rice. I had not been doing much and therefore wasn’t hungry. I tried to thank her and ate as much as I could. Then we moved on up country to Frankfurt.

Here we had huts, little shacks they put up fast, with just one man in each. This was an interrogation center - solitary confinement. They didn’t ask me questions, instead they told me who my CO was, the bomb aimer, what boat I came over on, the number of people on that boat and when I came over. They even knew how many bombing raids my CO had been on. They were just verifying what they already knew. I was amazed. We had quite a talk there. They could tell by the look on my face everything they said was true. They didn’t give me a hard time here like they did in Dusseldorf.

Fadden, who had bailed out the same time as me eventually found himself in a town and seeing a bicycle leaning against a store, proceeded to take it. A guard came out of the store and Whitey pulled a knife on him and ended up on the firing line. They gave him quite a hard time.

After being questioned, on my way back to my room, I saw Whitey making a face at me from his room, with his thumbs in his ears, waving his hands - the foolish fellow. I was glad to see him and we kind of hung out together. We were put in barracks with a group of others and waited there until they had enough prisoners for a train load. After three weeks we were moved on.

We unloaded at Stalag Luft VI, in Heydekrug, East Prussia. As far as I knew I would be here until the end of the war. As it turned out I was in this camp one and a half years. There were many of us crowding into the camp and looking for beds. We were the first fellows to settle in and the only person I knew here was Whitey Fadden. Later they brought up Americans and built an extension on the east side of our camp and kept them separate. Every four - six weeks another train load would arrive. They added another extension on the south side for British and Canadian airmen. Mother sent word that a fellow from St. John by the name of Fox was a POW and believed to be in the same camp. I called across the fence to see if they knew of a Fox. They said "Sure, Zeke Fox". Since Germany generally kept within the bounds of the Geneva Convention we were able to have a reasonable lifestyle.

We always felt hungry. I suppose after months went by your stomach shrunk up a bit. When Red Cross parcels were coming in, morale was good.

We would get up in the morning, go out and wash in cold water. Each hut was given large pitchers of ersatz coffee made from acorns and whatever else. For lunch we were given what was called turnip stew, which was more like soup and no stronger than their coffee. This was turnip and water and maybe a little salt. There were no chunks of turnip and you only received a tin full. We were given a tin cup for our coffee, lunch and anything else. We got turnips every day - even the turnip peelings were fought over by the prisoners.

One day, walking by one of the huts, I noticed a smell coming from there that would knock you down! Some prisoners had traded cigarettes with a German guard for a dog telling him they wanted it for a pet. Sure enough, they were cooking the dog and having him for their supper. The smell was awful!

You would also see fellows sprinkle crumbs of bread on the ground and set a trap for a bird with a tin can and a string attached. They would lie there for hours, perfectly still, waiting for a bird to land for the crumbs, then pull the string and trap maybe a sparrow. I imagine they got some, otherwise they wouldn’t lie there so long. Who knows?

From the Red Cross we also received cans of powdered milk about the size of a tobacco can. This was labeled Klim Tin (milk spelled backwards). Those multi purpose cans were just the greatest! Prisoners made cups from them, heated water for tea, or made porridge in them. You could also heat water and give yourself a good wash in a Klim Tin. They were even used to make blowers.

We were able to heat our food on blowers. They were little stoves we made consisting of a fan, with a little shaft leading into a fire box and you’d put little chips of wood in it and get a fire going. We mostly enjoyed coffee and porridge heated on the blowers.

Every day after dinner the fellows would wash their dishes out and throw the dirty water over a board with a warning sign posted on it demanding they not go beyond that point. I watched as one fellow threw his water over the board and the guard fired at him and hit him in the arm.

Another time, a German guard high up in a tower received word his family had been bombed. He just let his machine gun fire all around our feet. Tore the ground right up in front of us. It was just a burst. We stopped for a second but didn’t want to stand there too long - he might open up again, so we just kept walking and stuck together.

During the spring hundreds of tadpoles could be found in a small stream running along one side of the camp. Summer in the prison camp had several disadvantages such as dust and unpleasant smells. Flies were extremely annoying and dangerous, outbreaks of dysentry frequently being caused by these pests. Wasps were also really bad. Attracted by numerous Red Cross jam tins, they arrived by the thousands.

During the long winter evenings, the lights were too dim to read by. We only had two little windows in each end of the 60 foot buildings with three tier bunks on each side. The only place I did any reading was at the library which was closed in the evening.

One day a fellow arose early and with his towel thrown over his shoulder, headed to the washroom. It must have been before 7:00 for we weren’t allowed out of our huts before then. The guard shot him in the stomach and just left him there to die. We watched this and were totally unable to do anything. None of us could leave our hut or we’d get it too. He suffered there for an hour. It was just awful.

It was fantastic what the Red Cross parcels brought to us. If it hadn’t been for them I wouldn’t be here today. When they would arrive, we’d take it off to a corner and nibble on the food like a mouse. After awhile we pooled things like jars of jam. We would only open one at a time and share it. This didn’t last long for we found some guys would always take more than their share. In a prison camp on rations, behaviour like that doesn’t go over very well. Cheese would also arrive in these parcels. Some had been on ships a long time in the heat and by the time we received them, the cheese would have huge worms.

These Red Cross parcels were intended to supplement the rations provided by the enemy. One parcel was to last each man one week. But they rarely arrived that often.

There was one case of theft I remember. A fellow had been guilty of raiding the lockers of seventy-five or eighty guys while others were on parade. One fellow got angry and searched all the bunks and their kits as well. He found the culprit, marched the guy out to the washroom, tore up some of the boards, and threw him in the waste. He pushed him down under again and again, head and all, until he was good and soaked. When he finally was allowed up out of that awful mess, was he mad. Swearing and cursing and shaking that mess off him and onto people close to him! That was the only case of thieving I ever heard of.

We would get mail every four or six months. We had a little type of post card/letter. It opened up so you actually had two post cards and you could write in there. We were always happy when a mail day came, unless you were one of the fellows receiving `dear john’ letters. All letters were censored by the British government to stop people from sending information to Germany; and then the German government would censor to prevent you from getting information they thought might be useful to you. Sometimes a letter would come with just the `ands’ and the `the’s’ left. The rest blotted out.

Cigarettes were like money. You could swap or barter anything. The Red Cross supplied 50 cigarettes a week. Some Canadians received cigarettes from home. We made up trading stores. If you had cigarettes you could buy anything. There was more smoking going on there than eating, that’s for sure. I never smoked while a POW and at bedtime it would get pretty smokey in your hut with nearly everyone smoking (100 - 150 men).

In the morning and evening, for about an hour or more, we would walk around the rows and rows of huts just inside the warning line. The Red Cross supplied us with a library and you had to wait your turn for books. I had received word from home that father had bought a farm for me (the Davis place for which I paid upon my return) and it had a few apple trees. I sent for a book from the Red Cross on pruning apple trees. It took six to eight months to arrive but I finally received it and made many notes. I still have the notes on farming I made in the prison camp.

We received seeds as well. Most men didn’t want theirs. I tried growing a little garden no bigger than a kitchen table. I had lettuce and radish planted and a sunflower seed in each corner. Not much came of it. Some fellow would tear them out each night, though I did get to enjoy some of it.

We had a billet for entertaining or holding meetings in. About once a month we would find a notice on the bulletin board for the opportunity to go and enjoy some records a fellow would play for us. Those records really sounded like home and made you lonesome. I was only there four or five times. Only one evening I remember well. In the warm weather I became quite creative and turned an old blue shirt into a pair of shorts. I had a great tan that summer. Sure was cool and nice.

Aunt Jessie sent me a blanket from home. It was white with pink stripes across the ends of it, and was far superior to the regular ones we were given. One day I hung my blanket on the fence to let the wind blow it out. I forgot it and asked the guard for permission to go and get it. He told me I’d be fine. You couldn’t really be sure of the guard in the tower so I decided to leave it there and get it the next day.

Some fellows tried making a rink by flooding from the washroom, but the ground was slanted and the water went down hill. It didn’t quite work. We were able to play cards a lot, also rugby and baseball. Some of the boys were digging tunnels and would put sand under their shirts and pants and would gradually drop the sand out of their clothes while running around the bases playing ball.

In March, 1944, 76 men made a great but brief escape from Stalag Luft III at Sagan in occupied Poland. Three escaped, the others were rounded up and 50 were shot, including six Canadians. We were made aware of this and upon hearing of the shooting, everyone booed the German officer who informed us. The tunnel in our camp didn’t get out in the woods far enough. They kept a stove over the entrance to the tunnel but the Germans found it. They took some of the boards from our beds and our mattresses as well, so we couldn’t build tunnels with the boards. We were left with only three boards to lie on. One under our head, another under our rears and one under our feet. A friend and I decided to sleep together and share our boards. Many fellows did that.

The German authorities used to parade us twice a day on a head count, in the morning and then again around 4:30 in the afternoon. We were lined up in six rows and were all counted. The Germans would find that they would be eight men short. As we were standing in rows, some fellows would step back and ahead from different lines causing the guards to come up short each time. They would count and count. Sometimes we’d be standing there till dark getting a great kick out of this. The guards would get quite worked up

One day, as a guard came to get us out for parade, a prisoner lying in bed said he was too sick to be counted. The guard poked him with his gun, swore and told him to get out there. The prisoner grabbed the guard’s gun. I got right out of there. I don’t think they bothered with him. I think he’d let them shoot him before he’d get up.

The Germans were beginning to hear how their men who were held as prisoners in Canada were pleased with how they were being treated. This made the Germans happy and so they decided to give Canadian POWs preferential treatment for treating their people so well. One morning they came to take us out for a walk outside the camp but our camp leader said "They’re doing this to cause hard feelings between us in the camp". So we decided not to accept the offer. I did get out with a couple of prisoners and two guards for a walk in the country. I can’t remember how that came to be.

One Christmas the boys got hold of some women’s clothing and they put on a great show for the men. They played some records, wore wigs, silk stockings and painted themselves up with rouge. They had a great time and the show was enjoyed by all.

Another Christmas I tried to make a cake. Some of the boys and I saved up some big thick white crackers and crushed them up with water or something to make a dough. I decorated it on top with jam. It was quite a good size.

Death March.

(Although this was not the historic "Death March", we prisoners commonly referred to it as the Death March.)

One day in January, 1945, without explanation we were put on a boxcar headed south. We had tied up some of our belongings before moving on. I had to leave the blanket Aunt Jessie sent me, but I did take a thinner one. The train was really long and we were crammed in like sardines. If you had to go to the bathroom, there was a pail in the corner of the boxcar with sand in it. No one used it much. It was degrading. Everyone was in a sort of stupor - just sat there and stared. It took a long time to get anywhere.

We were put in a vacant prison camp, Stalag XX A in Thorne, Poland. We all had showers and the stink was something awful. We knew the Jews had been killed there and had been buried in a trench with dirt bulldozed over them. After awhile you got used to that smell. You sure knew it was death.

The guards were mostly older men. One German told me "We don’t want this war". I knew they would be shot if they didn’t do their job. We marched to Fallingbostel, Stalag XI B.

I had over 1,000 cigarettes on me during the march, and I traded them with a fellow for a pair of pyjamas. He came back later and told me they were too damp to smoke. We had been sleeping on the ground and it was pretty hard to keep things dry. I told him I’d trade them back, but he decided he’d keep them instead. We stayed here about two weeks.

We marched on to Germany, from seven in the morning until seven at night. We found that in parts of Germany they would harvest their crops and pile and cover them with straw and dirt. So when we’d stop for a rest, somebody would investigate, and then some would help themselves to this food. We would get potatoes and onions that way. If caught, the Germans would open machine guns on you.

A lot of fellows became sick along the way. We had nothing to eat. At one farm we found a big bin with crushed oats in it for the pigs. Some fellows had a screen and sifted the hulls out. I didn’t have a screen so I cooked up the oats and ate them hulls and all. That nearly ruined my stomach. I suffered a lot from that. I was so sick that I wished I’d die. I had ulcers for a long time after I was home. I did receive bottles of medicine from the DVA Hospital in St. John for quite awhile, at no charge.

My friend went to a house and asked to borrow a needle and thread. They gave him something to eat. Meanwhile, I was out behind a shed and found onions they had thrown out. They had been frozen and were starting to spoil. I cut the spoiled parts out, cooked them up and ate them.

There was an army doctor in prison with us. Everyone went to him telling their problems. All he had were little white pills which he gave to everyone. They never really helped. I was sick for two or three days.

We usually slept out in the fields or by the side of the road. Occasionally we would stop by a barn overnight. Some fellows may have slept in the barn. I only slept in a barn twice. Our physical condition was worsening. Some started breaking out in boils. Sometimes the guards would poke you with a rifle butt to push you on. Some were bayonetted in the rear for not moving fast enough.

We ended up in Fallingbostel, Stalag XI B. This camp had tents so we slept on the ground. Here, some fellows drew scenes from prison camp. They were making a book of sketches on life as a POW. A paper was posted and if anyone wanted a copy of the book they were to sign up and it would be mailed to you later. I am happy to have a copy, entitled ‘Handle with Care’.

Near the end we were in groups of about 500 men. Whenever we saw any of our planes flying above, we’d jump and wave at them. One day we prisoners were sitting on one side of the road and the guards were on the other having their lunch. Ahead we saw men running. I looked up and saw an American fighter, a Mustang maybe, flying low coming right at us. We knew they were going to open fire, so I ran for about eight feet through bushes, dropped right down on my belly and buried my face in the dirt. Seven planes came at us, one at a time, circled and came back again, thinking, of course, that we were German troops. They fired, I got up again and ran further into the field watching for the next group. I hit the dirt again, my face ploughed into the sod. They were dropping torpedoes and firing machine guns. I got up and ran again, and so on. Someone’s foot was blown off at the ankle and it landed right in front of me. No blood, just blown right off. There were thirty men killed and well over 100 injured. Some of the men gathered up the dead and laid them in a barn. In walking through the barn I saw they had laid the bodies in two rows. The wounded were transported to a hospital. After that, anytime we saw a plane we’d head for the woods.

Some fellows took food off the dead bodies but I couldn’t bring myself to do that. We stopped at a house, knocked on the door and asked the woman for some bread. She couldn’t understand us so the man of the house came and asked her to give us some food. The next day we marched ahead to a barn. Names of the men who had been shot were posted on the outside of the barn. If we knew any of these people, we were asked to put our names down by the deceased. I recognized a couple of people so I wrote my name by theirs. Zeke Fox, we called him, was one of the fellows and my name was sent to his family. I was later contacted by his uncle for some information or details.

Along the way we arrived in a small town and it was said that Red Cross parcels were being stored in a vacant building here. Because of fuel shortages they couldn’t transport these parcels. The German guards found the building and we were issued a box a piece. We left a lot there for we were down in number to about 300 now.

One of the POW leaders on the death march had a little radio and would sneak the news to the men about once a week. We knew the end was near. Some fellows just took off on their own for Brussels or other places. The American and English troops were coming our way so many left on their own to meet up with them and be flown back to England. German guards were leaving as well. During the last month one or two would drop out at a time. Finally, only one German officer was left with us. Our group was now down to about 30 men.

Once, while on a country road, we caught some chickens, gathered poles, and right there made a fire and cooked them. The next day an Englishman appeared on a motor bike. The German officer wanted to get rid of his hand gun so I asked him for it.

The Englishman told us there was a plane ahead that would take us to Brussels. This was where we were liberated. I tried to get a halter on a horse. The Polish fellow tending the horse for the Germans tried to warn me not to take it - the horse wasn’t safe. I couldn’t understand the language so kept on. The horse kicked me in the stomach with both hind feet. Down I went with the wind knocked out of me.

There was another fellow nearby trying to hot wire an old car with a folded down top and big seats. Eight of us jumped in and away we went until we found the airport. We met Allies coming on APCs (Armoured Personnel Carriers) and asked them for gas. They threw us some white bread. We took big bites, it was just like cake. The German bread we had been given all along was so dark, nearly black. They flew us to Brussels.

We spent the night in Brussels and the Red Cross looked after us. We showered, deloused and had supper. In the evening we walked along the streets. The Allies had taken over. I can’t quite explain how I felt, except that my stomach was bad. There was so much happening all at once.

I was able to take home some needle nose pliers which I had taken from an old truck, and some German money I got from going through some German officers clothes hanging up in some empty buildings. I still carried with me my note book on farming, my Prisoner of War book and the little German hand gun.

We arrived in England, were taken to London and my stomach was really bad. There was lots of room here. We showered and deloused again, were given fresh clothes, and went down to a lovely dining hall. There were lots of young girls waiting tables and plenty of rich food, ham, eggs - everything. With my stomach so bad I ate very little while others just wolfed it down. We were here only one night and were sent on to Bournemouth the next day to be rehabilitated.

Going Home.

Our stay in Bournemouth lasted about a month. What a switch after being in the prison camp for two years to the month! We were put on special diets to build us up and about every two feet on the tables were large bowls of vitamins. I began eating light and could gradually eat more. I gained thirty pounds in one month. When I arrived I weighed about 98 pounds. Here we just laid on the beach, watched girls and walked in the parks and walkways. It was just beautiful. In the evenings we visited the pubs.

After two weeks we were given money and were told to go by train to South Hampton and buy a uniform, trench coat, club bag and cap. All of these I still have today.

A French boat, the Louis Pasteur, came in to transport us back to Canada. It just had hammocks hanging everywhere to sleep on. Whitey took one look at the boat and said he wasn’t going on that thing! I took advantage of the opportunity and when we landed in Halifax were instructed to go on to Montreal. We traveled by train through Bathurst and the lower Gaspe. The countryside here was quite a let-down after all the beautiful scenery I had seen. We stayed in Montreal a couple of days with doctors checking us, listening to our concerns and caring for our wounds. We went through commissions. I went from a Chief Warrant Officer Badge to a Flying Officers Badge.

I sent a wire home to tell the folks I was on my way. The wire simply read "Coming Home". I neglected to say what time and which train I would be on. Father walked to meet the train morning, noon and evening. I arrived the next morning at 9:00 all excited and worked up. Father met me and I thrust my hand out to shake his. I had forgotten his hands were crippled from the burns he had received while working for the Hydro Co. wiring an airport in Pennfield. We walked home and after all my travels I really didn’t think the Jct. looked like much. If it hadn’t been for mother and father I’d have been off again. I enjoyed a month home with pay - then back to Montreal to get discharged.

|

Edward Gurmin 78 Sqd From Dishforth I went up to Middleton St. George which was a brand new drome, now Teeside airport, they were just building it then. We went up there on Whitleys and I was flying with Chris Cheshire, who was the brother of Leonard Cheshire VC…he was my skipper. I did 23 trips on Whitleys and then they were bringing out the first of Halifaxs and they were forming a second Halifax squadron at Middleton St. George. It was similar to the Lancaster… we went on to the Halifaxs…in those days you had to do 30 trips over Germany and then you were taken off. We were briefed on 12th August, for Berlin. When we got to the outer defences of Berlin we found the petrol consumption had gone for a real burton. We didn’t have enough petrol left to get back to England…we thought wed try to get into the North Sea somewhere. We hadn’t dropped a bomb then, so we decided to drop the bombs on the secondary target which was Hamburg. So we did a deviation …dropped the bombs on Hamburg.I was on the wireless that night. The observer dropped the bombs. He gave me the thumbs up the bombs had gone. I sent a message back to Middleton St. George saying “operation completed” I got a message back from them saying “message received and understood” and just then there was one Hell of a bang. So I was on the wireless and had two switches, one for the wireless and one for the intercom. I was still on the wireless and I thought I’d better find out what’s happening here. So I pulled my plug out of the wireless, pushed it into the intercom just in time to hear Cheshire saying “Jump for it boys” and I couldnt believe my ears. I said “What do you mean…bale out?” and he said “Yes, and bloody quick”. We’d had this bump - he had the stick and moved the stick and just had nothing at all there. When we baled out we realised wed had a direct hit with an ack ack shell in the fuselage. The whole of the fuselage had gone. All that was left was two wings and four engines. The rear gunner, of course, hed fallen 15000 feet, he was dead. At the same time we were attacked by a night fighter and he killed the front gunner, as I say luckily I was on the wireless that night. Five of us managed to bale out…and of the five who managed to bale out four have since died, including Chris Cheshire ..so I m the only one left. We jumped out at 15000 feet – of course when I hit the deck it was one oclock in the morning and I didnt know where the rest of the crew were…they could have been ten feet away or ten miles away. I was hanging up there and the plane crashed below me. So I got out of my parachute. I actually fell into a bog and I couldnt get out of this bog. Everytime I tried to move out of it I was sinking in the bog. And that night another plane from our squadron was shot down and the whole seven of the crew baled out safely and five of them dropped into these bogs and drowned…so there was only two survived. Five of them drowned in the bogs that I was actually in. Anyway in the moonlight I thought I could see a bit of a path so I took a deep breath and ran like hell towards this path… I managed to get onto this little path and get out of these bogs. I was walking down the road and I was whistling “There ll Always be an England” thinking there may be some of my mates around…so Im whistling this and suddenly a Luftwaffe officer and ten squaddies came round the corner and grabbed me and took me to this ack ack post, that had actually shot us down.

|

Sgt. Reginald James White 51 Squadron (d.16th Jan 1942) I know very little of my Uncle Sgt. Reginald White, he was my mother's elder brother, he served with the RAF in 51 Squadron and died at the age of 19 when his Whitley bomber was shot down. He was a rear gunner.

Members of my family have visited his grave at Rottevale in Holland. Recently his younger step brother visited, and was very surprised at the welcome and hospitality shown by the villagers, who still hold an annual service for the war graves in their local parish church.

All the facts I know are below, and were gathered from this site, where there are details of the two other brave young men who lost their lives that night.

The bravery of young men such as my Uncle are an inspiration to me.

He is buried in the cemetery of the Protestant Church in Rottevalle along with two of his fellow crewmen who also lost theirs lives that night

However there is a mystery in that the graves state that they were killed on 23rd October 1942, yet records show that it was 15th January 1942 at 1758 they took off from RAF Dishforth.

Their aircraft was a Whitley, number Z9424 of No. 51 Squadron RAF.

There are rumours that the crew were injured, and locals hid them, but unfortunately they died of their injuries and were buried much later in secret.

His last mission was a bombing raid at the port of Emden. The aircraft was shot down over the Netherlands by the German night-fighter Unteroffizier Kurt Zipperlein, 4./NJG1 and crashed down at 0330 in Rottevalle. Three of the six crew members died in the crash, they are buried here. The other three crew members were taken prisoner of war by the Germans.

The graves are for:

- Flt. Sgt. (Air Ob.) Sydney Clarence Camp, R/71752, RCAF, age 23

- Sgt. (Pilot) Eric John Richards, 1162205, RAF, age unknown

- Sgt. (Air Gnr.) Reginald James White, 624058, RAF, age 19 (my uncle)