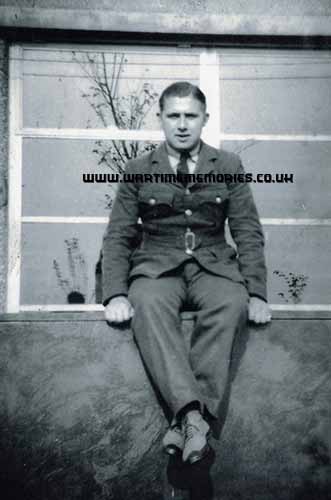

F/Lt. David Ronald Bradley DFM. 35 Squadron

The Pink Tape, by David Bradley

This is a true story of a happening over 50 years ago, and even today I remember it as if it were yesterday.

I dedicate this to Squadron Leader Wyndham Owen D.F.C. my pilot, who to me was one of the finest pilots of Bomber Command and a man of cool nerve and great courage.

Not forgetting my fellow crew members:

- Flying Officer Jock Cruickshank navigator (killed)

- Flight Sergeant Bill Martin R.C.A.F. Bomb Aimer (killed)

- Flight Sergeant Billy Young mid upper gunner (killed)

- Flight Sergeant Freddie Bourne rear gunner (killed)

- Flight Sergeant Bill Allen D.F.M. flight engineer, my fellow evader (later killed in a Mosquito in 1944).

I recall a description of the Crews of Bomber Command as 'Gentlemen of the dusk, minions of the Moon'. They were so young, so brave.

Chapter One

It was in the May of 1942 that I arrived at No.19 Operational Training Unit, Kinloss, Morayshire, having completed my Wireless Operator/Air Gunner course and sporting the chevrons of Sergeant on each arm. That course had taken place at Eveton on the Moray Firth and upon completion and with brevets awarded, posting to Kinloss followed. I was to form part of a crew that would commence operations with Bomber Command against Germany. I was twenty years of age and fulfilling an ambition to fly against the Germans who had been instrumental in starting this dreadful war against England. Like so many others, I gave not a thought to death or being maimed, it was just a matter of flying against the enemy and having a fairly exciting time. Both my elder brothers, Wilfred and Victor, called to the colours at the outbreak of hostilities, had been in the London Scottish Territorials before the war.

After completing arrival formalities at Kinloss instructions followed to attend a meeting held in a large room adjoining a hanger situated on the edge of the airfield. There were about fifty aircrew already in the room. Pilots, navigators, bomb aimers and air gunners, some already commissioned and the others of Senior NCO status. All were in their early to mid-twenties. Soon small groups of acquaintances formed chatting gaily. The main door opened and the order "Attention" rang out. Into the room stalked a Wing Commander, heavily built with a large black moustache, he also sported pilot's wings and the ribbon of the Distinguished Flying Cross.

"Gentlemen, I am Wing Commander Robinson - officer commanding this training unit. It is my task to group you into crews of six and, when that has happened, you will commence a four week training course. Upon successful completion of that course you will be ready to join an operational squadron. I will state, however, that no crew will leave here until I feel completely satisfied that they fulfill all operational requirements."

"This is just an initial talk to outline what will happen to you at Kinloss. For the first three days you will attend lectures. Following the lectures you will carry out daylight flying for one week and then a period of night flying. This entire course should take about three months, but Bomber Command is short of crews and your training has to be concentrated into a much shorter period."

"The aircraft available to you are ex-operational Whitleys. They are in very short supply and must therefore be treated with respect and not pushed too hard. I shall come down very heavily on any crew member who disregards this warning. You will be pleased to hear however that operational squadrons are now receiving deliveries of Lancasters and Halifaxes. You will not, of course, be able to familiarise yourselves with four-engined bombers until you join such squadrons. In the meanwhile you will learn to operate as crews on the twin-engined machines available."

"It is not my intention to form you into crews myself but rather to let you talk among yourselves and see if you can crew-up without outside help. You have one day in which to complete this very important task and, tomorrow when we meet again, I shall expect to find you seated in groups of six. Thank you Gentlemen."

I looked around the room. There were air gunners and wireless operators that I recognized from the gunnery school, so perhaps, there would be no difficulty in finding one or two to crew-up with, but, that would be only part of the team.

"Excuse me, but I am looking for a WOP/AG, have you crewed-up yet?" I turned to find myself confronted by a tall grey eyed Pilot Officer wearing the wings of a pilot.

"Good morning Sir" I replied, "No, I'm not fixed up yet and was just wondering how to go about it." The pilot held out his hand.

"I'm Wyn Owen by name and, if you are agreeable, that makes two of us with four more to find." Pleased to have found a billet, I immediately agreed.

"I'm David Bradley, do you mind if I call you Wyn?" The pilot smiled,

"That's fine by me David, perhaps we should find out a little more about each other. For my part there is very little to tell. I was at University until war broke out and, although already half way through my studies and twenty years of age, I decided that I would much rather be a pilot. So here I am !"

I found myself immediately liking my new found skipper and supplied my own brief history.

"Tell you what Wyn, why don't I try to find some more members over a lunch-time drink in the Sergeant's Mess. I've a pretty good idea who we shall need and, if I'm successful I could bring them back after lunch for you to vet." Wyn thought that this would be a sound way of approaching the matter and set off for lunch leaving me to see what I could do. Leaving for the Mess I caught up with another air gunner by the name of Freddie Bourne who had been with me at the gunnery school.

"Fixed up yet Freddie?" Freddie shook his head.

"No, how about you?" I outlined what had happened so far and explained the arrangement with my new skipper. "Well, how about me then David, can I join?" I already knew Freddie fairly well and quite liked him. He was of slim build, also in his early twenties, engaged to be married and lived on the eastern outskirts of London. I quickly decided,

"It's alright with me Freddie but of course the skipper has the final say." Freddie agreed that of course this was so and was quite happy to wait and see.

"Tell you what David, I met a bomb aimer on the train coming here, a Canadian and quite a likeable type. If we happen to find him in the Mess I'll introduce him and you can see what you think." The bar did not open until mid-day and we sat in the ante-room in parched anticipation. Men passed in and out but no familiar faces until Freddie called out

"Hey Bill, Bill Martin, over here."

"Hello Freddie, nice to see you again, I was beginning to think that I would never see a friendly face among all these strangers." Freddie introduced me and explained that we hoped to be in the same crew. Bill had recently completed his training in Canada and was just off the ship. There was something about his manner that appealed to me and, after all I was looking for a bomb aimer.

"Tell me Bill, have you crewed-up yet ? If not, why not come over and meet the skipper after lunch?" This idea appealed to Bill who suggested that they get better acquainted over a drink at the bar. Having managed to reach the bar through the thirsty crowd we obtained our drinks and settled down to talk about the service and flying.

Time passed quickly and, after lunch, we made our way back to the crewing-up room. There were still many men in the room but they were now in smaller groups. Crewing-up was obviously going ahead successfully. Looking around the room I eventually located Wyn Owen who was standing talking to a Flight Sergeant Air Gunner/Wireless Operator who wore the ribbon of the Distinguished Flying Medal. Indicating that Freddie and Bill should follow, I led the way across to where Wyn was standing.

"Ah, there you are David, this is Flight Sergeant Hoggins, I have asked him to join us as wireless operator." I was completely taken aback, I had expected to fill that position myself. "Flight Sergeant Hoggins has only ten more trips to do to complete his tour. If you have no real objection to flying as mid-upper gunner for our first ten trips, when he has completed his tour you then take over as wireless operator and we get a new gunner for the mid-upper turret."

This suggestion was quite reasonable, and I could find no good reason to object, after all, we were getting a seasoned crew member who would obviously be very useful during their 'shaking down' period. Agreeing to this arrangement I introduced Freddie and Bill. While Wyn was talking to the newcomers I got into conversation with the Flight Sergeant who, asking to be called 'Oggie', explained that he had completed fifty bomber trips and would shortly be grounded. Just as 'Oggie' was apologising for taking the wireless operators position Wyn turned back to us and said,

"I'd like you to meet our navigator, Jock Cruickshank". Jock was a short young Sergeant. There was only one member missing, the Flight Engineer and he apparently, would join us at the conversion unit on the squadron.

The weeks that followed passed in lecture rooms and on day and night flying. The crew got on well together and it became obvious that Wyn Owen could handle plane and men equally well. During training the emergency procedures we were taught included parachute drill, crash landing drill and ditching procedures. The course lasted for nine weeks and on the last day the crews gathered for a final talk by Wing Commander Robinson. He was, he said, satisfied with the results attained and wished us all well for the future. In parting he stressed that flying over Germany was not a simple task - the enemy was tough and ruthless. Attacks should be pressed home to the best of our ability and no crew should ever relax until their aircraft was safe back on the ground.

The following day Wyn Owen was able to tell us that after two weeks leave we were to meet up again at Linton-On-Ouse in Yorkshire where we were to join No.35 Squadron. I spent my leave at my parent's home in New Malden, Surrey and, with all my friends away, I quickly became bored. Saying farewell to my parents was not easy, they knew what I was about to do and in those days, losses over Germany were heavy.

Arriving at Linton-On-Ouse to join 35 Squadron and allocated a room in the Sergeants Mess I then made my way to the ante-room where Jock Cruickshank and Freddie Bourne were waiting. Greetings exchanged, each was anxious to be first in telling the others that the station was Halifax equipped. Just as we were enthusing over the four-engined machines a dark haired Sergeant of about twenty-eight approached us and said

"Either of you blokes Jock Cruickshank or David Bradley?" I made the necessary introductions and the newcomer replied "Oh good, I'm Bill Allen, I met Wyn yesterday and he told me to make myself known, I'm to be flight engineer on your crew."

Naturally we spent the remainder of the evening in the Mess bar and gradually the other members of the crew arrived. There were many operational crews in the bar that night and several wore DFM ribbons. From some of these, I learned that we were to begin our conversion onto Halifaxes the very next day.

Chapter Two

The conversion to Halifaxes lasted nearly throughout the month of August and the crew became very impressed with the aircraft that was almost twice the size of the Whitleys we had become used to. The first week of conversion consisted mainly of take-offs and landings that became all very monotonous and boring, during the second week however, a little excitement broke the monotony. All aircrews assembled in the briefing room for a very special announcement. Rumour was rife. The squadron was to be posted to the Middle East, from being on night bombing they were to change to special daylight operational duties, and many more. In all, there were about eighteen crews assembled in the briefing room when Wing Commander Marks DFC entered. He was a very impressive handsome man well over six feet tall.

"Please sit Gentlemen. Before I make any announcement I must impress upon you all the importance of what I am about to say, and stress the necessity for complete secrecy. Any person found discussing this matter off the station will be in very serious trouble. Need I say more." There was a complete hush in the room.

"The air war over Germany is gaining momentum and Bomber Command is becoming a very formidable force. Headquarters consider that we are not making the best use of the weapons to hand. Examination of photographs taken on bombing missions reveals that too many bombs fail to hit their targets. To overcome this a special corps d'elite is to be formed and will be known as 'The Pathfinders'."

"This group will consist of four heavy bomber squadrons chosen because of the very high results they have achieved during the past year. It pleases me to say that 35 Squadron is one squadron selected and this is complimentary to those of you who have already flown with the squadron in an operational capacity. The four squadrons will be based approximately fifteen miles north of Cambridge, one unit to an airfield. Group Captain Bennett DSO will be overall commander of this group."

"Every member of every crew will be more highly proficient than the average. On completion of ten trips he will take an examination on his subject and, on passing will be upgraded by one rank. He also will qualify to wear the Pathfinder wings. This emblem will be worn on the left breast pocket lapel, and will be the same eagle worn by officers on their sidecaps and will signify that the wearer is a member of the Pathfinder force."

"The task will be to light up the target area and mark it out by the aid of flares, these flares must be placed accurately as the main force following will rely on them completely. Failure by Pathfinders will cause any mission to be abortive. You now realise how important your new task is to be. Bombs will not be carried, only pyrotechnics. You must realise of course that having to lay out an aiming point in the sky is an extremely hazardous task and will attract that much higher degree of danger." He paused.

"On this aspect of extra danger, added to an already dangerous job, I am only calling for volunteers. I want pilots to discuss this with their crews and advise me tomorrow if they wish to be members of this force. Any crew not willing will be posted to another ordinary heavy bomber squadron and shall not be thought of any the lesser. That for the moment is all the news I have for you, except that tonight, there will be no operations. I shall see you here again tomorrow morning at 1000 hours."

They all stood to attention as he left the room and, immediately the door closed, the talking began.

"Wyn, do you think that we will be acceptable seeing that we haven't done any ops yet?"

"Well, we haven't put it to the vote yet and there's no point in talking further until we get that settled, so let me have your opinions."

All were in favour immediately except 'Oggie', who pondered awhile before answering.

"Well" he said, "I've risked my neck fifty times already so I suppose another ten won't make all that difference to me. O.K., count me in."

Wyn smiled.

"Well, as I happen to be keen on it as well, that makes it unanimous and, whether we will be acceptable or not, I'll put it to the Wing Commander at lunchtime and let you know later."

The crew made their way back to the Sergeants Mess discussing this new scheme. Their conversation continued in the bar, right through lunch and well into the afternoon. The over-riding query was - Would we be accepted? The topic finally dropped when Bill and myself went into York for a few pints at Betty's Bar. York was full of aircrew indulging in their favourite pastime of emptying pint glasses.

As instructed the crews assembled again the following morning where Wyn told us that we were acceptable for the Pathfinder force. Wing Commander Marks announced that every crew had volunteered and that the result delighted him. "I did not have all the available details yesterday Gentlemen, but I am now able to confirm one important aspect concerning the number of operations you will do with the Pathfinders. As you are aware, on a normal bomber squadron, you complete thirty operations and then you go on rest for six months. This followed by a further thirty operations after which you retire for good."

"With the Pathfinders the rules will be different. Owing to the very hazardous element involved, and the high degree of efficiency you will need to obtain and maintain, the requirement will be forty-five trips right off and then finish completely."

This to me was a reasonable requirement. There would be fifteen fewer trips to do, to allow for the added danger but, of course, no interim rest period.

"We shall be moving the squadron to Graveley in exactly two weeks time and, meanwhile, operations will be carried out normally. Please take great heed of my warning over secrecy."

Wyn and the crew flew the training Halifax on short, two to three hourly trips over England and became accustomed to handling the aircraft. Each crew member needed to become fully conversant with the machine and trained how to hold it on course and go through the rudiments of a landing. Wyn insisted on this so that, should anything happen to him, someone would stand a chance of getting the aeroplane down in some sort of fashion.

During the following two weeks the squadron carried out four operations with the loss of two crews. Rarely were losses mentioned as each crew convinced themselves that 'going missing' was something that only happened to others, not to them. Finally the day for moving to Graveley arrived.

Wyn and the crew had 'P' for Peter allocated as our machine. Brand new and our very own. As I remarked to Wyn while admiring the aircraft,

"I don't suppose it will be long before we have some bombs painted on the side of this kite, do you?" I was right, we were scheduled to be on the first operation to be carried out by the squadron from Graveley.

Within a week the squadron had settled at our new station. Gravely was a 'satellite' station, its parent being the station at Wyton. It did not have the comfort of Linton, like Wyton built before the war. At Linton the Sergeants living quarters formed part of the main Mess, whereas at Graveley everything was dispersed. The sleeping quarters, sited a quarter of a mile from the main Mess and the briefing room a further half mile on from that. The supply of Royal Air Force bicycles became greatly appreciated by the crews.

Naturally, the crews soon explored the area for entertainment. The village of Graveley was very small with a Post Office and one public house called 'The Eight Bells', that was very small with an old stone floor. 'The George' was also soon located, in Huntingdon. Once we found 'The Baron Of Beef' in Cambridge, twelve miles due south, we felt that we had settled in.

While converting to Halifaxes I learned from my parents that both my brothers had applied for, and been accepted, for transfer to the Royal Air Force as bomb aimers. I was not at all happy about this, with three brothers flying with Bomber Command, the odds were that something would happen to at least one of us!

On September 2nd 1942, the tannoy ordered all crews to report to the briefing room at 1000 hours that morning. "This is it!" We said. All the crews assembled well on time, anxious to hear what the target for that night was to be. The Wing Commander entered and instructed a Corporal to draw the curtains; a security measure to ensure that no person outside the building could look in and identify the target for that night. With the curtains drawn and the lights switched on the Meteorological Officer drew aside curtains covering a map of Europe.

"There is a provisional target for tonight Gentlemen, and there it is." He pointed to a spot on the map, "Saarbrucken, Carry on Intelligence." The Intelligence Officer took the stand and said that the industrial area of Saarbrucken was to receive attention. It was an important military target, not bombed for some time.

"The flak defences are heaviest in the eastern part of the area so you will be routed in from a southerly direction. As you can see, the route takes you directly over Norwich and then in a straight line to a point twenty-five miles south of the target area. You then change course in a northerly direction and should be over the target area at 0235 hours. Your flares are to be released at 18,000 feet, set to go off at 1,500 feet. The main bomber stream is timed to arrive exactly three minutes after dropping of the first identification flare. Further details will be given at this afternoon's briefing." Then followed a rather sketchy meteorological report followed by short talks by the leading Gunnery Officer, Signals Officer and finally the Navigation Officer. Wing Commander Marks stood up.

"Remember Gentlemen, we are still learning methods of lighting up targets and still have a long way to go. 'Accuracy' is the operative word. Under no circumstances drop your flares unless you are absolutely certain that you are over the target area. It is unusual to name the target at the first preliminary briefing but this one has been planned for some time. More details will be available at the briefing this afternoon. Thank you."

"By the way, will Pilot Officer Owen and his crew please remain behind."

"Now, Gentlemen" he began, "This is your first trip and I have given instructions for you not to carry flares on your first operation. You will be with the main bomber stream and carry high explosives. I want you to do the very best you can and may I personally wish you all the best of luck." When the Wing Commander had departed Wyn said

"Well lads, here we go at last" to which we remarked that it was not before time.

Parachutes collected, we rode out to 'P' for Peter to do a quick air test. Sergeant Russell and his ground crew were waiting for us. "Good morning Russ" said Wyn, "How's she looking?"

"Spot on Sir, absolutely in prime condition." Sergeant Russell was proud of the job he was doing.

Climbing aboard, each crew member checked his equipment. Engines revved up and 'P' for Peter taxied to the take off point at the beginning of the runway. Standing beside Wyn was Bill Martin the Bomb Aimer. With sufficient height achieved it was his job to pull the throttles back and set the engines at cruising speed. It took both hands of a pilot to hold a Halifax on take off. Wyn checked out every member of the crew and with a "Here we go!" Pushed all four throttles forward, released the brakes and set the aircraft roaring off down the runway.

Once airborne and at 500 feet he ordered "Twenty six fifty," this meant that Bill Martin had to ease back the throttles so that two thousand six hundred and fifty revolutions per minute were showing on the throttle gauges. The aircraft seemed to ease back and settle. After about twenty minutes and with all equipment checked, 'P' for Peter came into land and taxied to her dispersal point. The airfield was a hive of activity, pyrotechnics being taken out to the waiting aircraft and armourers topping up the ammunition for the Browning guns. There were not going to be many crews in Cambridge that night.

The others and I went to the Sergeants Mess for a non-alcoholic lunch and. We were not due to report for briefing until about one and a half hours before take off, so decided to spend the afternoon in our quarters. Only Jock, as navigator needed to attend the afternoon briefing with Wyn. Our sleeping quarters were in a large hut that we shared with the non-commissioned crews of two other aircraft. I kicked my boots off, lit a cigarette and stretched out on the bed. Turning onto my side I faced Bill Allen on the next bed. "Well, this is it Bill, our first operation at last, how do you feel about it now?"

"Bloody well scared," was the short reply.

"Quite frankly, so do I, here we are after all these months of training, ready for 'the off'."

Bill grunted, "Well, no good brooding over it, I'm going to try to get some sleep." He pulled a blanket over himself, settled down and I did not bother him further. He was the only married man in the crew

Stubbing out my cigarette, I lay back, thoughts drifting through my mind. How would we make out on this first operation? Would we be hit by flak? Would we be attacked by a night fighter? Would we get back to base? Forcing these fears from my mind I eventually slipped into a fitful sleep.

Waking around tea-time, I quickly washed and made my way to the Mess. It was a late summer's day, the trees just taking on early autumn tints, it just didn't seem possible that there was so much killing going on not so far away and, indeed over this beautiful country. In the Mess, I met Jock.

"From what I can gather," said Jock, "This target is a fairly easy one compared to some nasties, so I suppose that we should be grateful to get this one as our first operation." Freddie Bourne joined us.

"What time is take- off Jock?"

"Ten minutes past midnight and, if all goes well, we should be back at base about 0500 hours. Last briefing is at 2230." From tea-time until around 2200 hours seemed like an eternity and we spent the time playing cards. 'Oggie' who had joined the card game eventually suggested that we move off to the briefing room. "Come on lads, I know how you feel, it's nearly eighteen months since I did my first trip and was I scared!" Somehow this statement gave the others a little more comfort. At least one of us had been through it many times before and was still around to talk about it.

We cycled to the briefing room and made for our flying kit lockers. "Right" said 'Oggie', "Check everything carefully, parachute pack and harness, Mae Wests, gloves, helmet and flying boots. Take your time, if you hurry it you will be sure to forget something." Thoughts now concentrated on the job in hand, fears temporarily banished. Satisfied that we were equipped we made our way into the briefing room where Wyn awaited us.

"Hello chaps, come and sit over here. Nothing much to worry about, this target is a doddle." As each crew member sat he was issued with pandoras and a purse. Should we be shot down, these were part of the escape equipment. They contained silk maps, compass, a miniature box of matches, water purifying tablets, concentrated food pills and certain quantities of continental currency. The squadron commander entered the room.

"Gentlemen, the operation tonight is definitely on. There was some small doubt this afternoon concerning the weather, but this now has apparently resolved itself. I now want to introduce Group Captain Bennett who, as you know, is overall Pathfinder Commander."

A medium built dark haired officer wearing the ribbon of the Distinguished Service Order moved forward.

"Gentlemen, I have not had the pleasure of meeting you before although I have already met the crews of the other three squadrons. Tonight is your first Pathfinder show and I'll say little more at this stage. We will await results and see if this idea is really going to work. I am fully confident that it will. Our reputation stands or falls on the extent of your accuracy. Good luck to you all, and have a good trip." The briefing continued with the latest weather and intelligence reports and finished at 2300 hours. Take off time was to be at ten minutes after midnight.

Assembling our gear, the crews moved outside to await the coaches that would take us to our aircraft. Everyone was heavily laden, especially the navigators with their large green navigator bags and sextants beside their other flying gear. The coaches arrived, crews climbed aboard and were carried away to the awaiting aircraft. We arrived at the aircraft and were met by Sergeant Russell who reported that everything was in order and ready to go.

"Get your gear on board chaps" said Wyn, "Then come outside until ready for take off." Gear stowed aboard, we re-emerged and stood around talking and smoking. The ground crew arrived with tea. I left mine, my stomach not being very receptive.

The station commander drove up and chatted briefly with the crews.

"Everything alright Gentlemen?" Yes, everything was alright. "Well, have a good trip chaps and I'll see you when you get back." As Bill Allen remarked, anyone would think that they were going on a bloody trip to Margate. When it was time to get aboard I had great difficulty in climbing into the mid-upper turret. With Mae West and parachute harness worn over a thick Irving type flying jacket, there wasn't very much room. I hoped to hell that I would never have to get out in a hurried exit - I didn't exactly fancy my chances.

Engines burst into life and Wyn commenced his magneto check on all four engines. This completed, he checked out every crew member over the intercom to ensure that we were all plugged in and that there were no faults in the system. Aircraft after aircraft taxied out onto the perimeter track. 'P' for Peter finally reached the end of the runway and awaited take off.

Chapter Three

"O.K. chaps, here we go, good luck." Said Wyn. With a roar we hurtled down the runway precisely at the scheduled take-off time. With a full bomb load we climbed slowly until, at 500 feet Wyn gave the order, "Twenty six fifty." Bill Martin eased back the throttles.

"Give me a course please Jock."

"Zero nine eight."

As we climbed slowly, lights extinguished, I began to think over all the training I had been through, the people I had met, all leading to this, my first operation. I felt very scared indeed!

It was a reasonably clear night with just a few cloudy patches as we crossed the coastline and made our way over the North Sea. Half way across Wyn ordered a brief test of gunfire.

Turning the turret to one side, I pressed the trigger. The two Brownings burst into life. Freddie also fired his four Brownings. "Rear gunner reports all guns firing and O.K."

"Mid-upper gunner reports all guns firing and O.K."

The smell of cordite was very noticeable.

"We are approaching ten thousand feet, put on oxygen masks now."

Masks incorporating microphones were clipped on.

"Enemy coast ahead. We should cross it at eleven thousand feet. There is some flak out over on the port side, everyone take a look so that you will recognize it in future."

"Crossing the enemy coast now. Everyone keep their eyes open for night fighters." We had already been warned that the main fighter belt was eight to ten miles inland from the coast.

"Levelling off at eighteen thousand now."

We flew on, alone it seemed, with no other aircraft in the enormous black sky. It became very cold and I felt it particularly for, unlike the others in the forward part of the aircraft, I did not have the advantage of heating. There was some consolation in the fact however that Freddie, in the rear turret would be even colder. Poor fellow, out there on a limb, entirely on his own.

A change of course was made and we flew on until Bill Allen called out "Target area ahead." In his position on the flight engineers deck just behind the pilot he had the use of the astrodome just above him, and a complete view encompassing three hundred and sixty degrees. Bill Martin went down into the nose to prepare for the run in.

"My God, Wyn, look at those flares and fires below" called out Bill Allen.

"Bill, I can see them very well thank you, now, no unnecessary talk please." Wyn spoke in quietly composed tones.

The target had been clearly identified by the flares. Estimated time of arrival over target - one minute. "I'll follow your instructions now Bill" said Wyn.

Bill Martin guided us in. Bill Allen reported flak close on the port side.

"Target in sight now and bomb door open."

"Bombs gone."

The mighty aircraft, relieved of its burden, rose into the air.

"Bomb doors closed."

As Jock gave Wyn the course for home, we could see Saarbrucken below us clearly lit by numerous fires and by the flares in the sky, now burning out.

The target area slowly disappeared behind us, w were on our way home to a warm briefing room, hot tea, a good breakfast and to bed.

It was no time to be complacent. "Everybody keep their eyes open, we've still a long way to go and the bastards will be looking for us." Wyn was taking no unnecessary chances.

Luck had it that the return journey was completely uneventful. Gradually we lost height and crossed the English coast at seven thousand feet. Hot coffee was handed around and we all felt elated; we were on our way home, the first operation completed.

We landed at 0530 hours and taxied to the dispersal point and Sergeant Russell. Engine covers were placed over the nacelles and the crew bus took us back for de-briefing.

Many questions were asked concerning flak, sightings of aircraft, both British and German, and about the weather conditions. All this took about half an hour. The large blackboard that showed landing times of aircraft revealed two blank spaces.

De-briefing over, we walked back to the Mess and the eagerly awaited post operational breakfast - bacon and eggs! Everyone who had noticed, thought silently about those two blank spaces on the blackboard.

Breakfast over, I and the rest of the crew made our way to our sleeping quarters and, despite the excitement of the first trip, soon fell asleep.

To me, it seemed that only minutes later I was awaken by a light shaking of his shoulder.

"Sergeant Bradley" the intruder said, "There are operations today and you have to report to the briefing room at 1100 hours." I sat up and looked around the room. As I had feared, there were six empty beds. They had gone missing.

The subject of the vacant beds was not raised as we made our way across to the Mess, although there was a great deal of talk about the previous nights mission. Entering the Mess we noticed a few new crews, all young men like ourselves. From the general talk there seemed to be a bit of a flap on.

A second breakfast was disposed of before reporting to the briefing room. On arrival we were informed that there would be a further operation that night and that aircraft should now be air tested.

The air test completed, Bill Allen and myself strolled down to Graveley village and the pub. We both admitted that we had been scared the previous night and Bill stated frankly that he could not see us completing forty-five trips, the law of averages being that, after seven trips you were on borrowed time.

Though I tried to reassure him I could not but help feeling disturbed within myself. In my own mind I was sure that all would go well but nevertheless, there were forty-four more dangerous trips to complete! This gave me considerable food for thought on the way back to the airfield.

The afternoon preliminary briefing was held and, as soon as Jock returned to the Mess, we collared him.

"Right, where are we going this time?"

"Karlsruhe, and it should be a fairly easy trip. Take off is at approximately 2300 hours."

The rest of the day was occupied as before and, as drinking was forbidden, the time dragged by.

At briefing we were told that this was to be a maximum effort involving eighteen crews. The previous night mission had been a success and Group Captain Bennett was delighted with the results, This could definitely lead to new bombing tactics.

Once again 'P' for Peter carried high explosive and, although there was little opposition over the target, two aircraft did not return to base.

At the end of two weeks, Wyn and the crew had completed seven operations and began to regard ourselves as veterans. Losses continued to occur, even veteran crews. Replacements arrived promptly; new faces and new personalities. Operations were always accepted without much grumbling, but there was always an underlying tension until the target was announced.

We all became quickly accustomed to seeing flak and gave it very little thought as we approached the target, although it was so thick at times that passing through it unscathed seemed an impossibility. Often shells burst nearby and shrapnel could be heard hitting the side of the aircraft. When this happened nobody panicked, we were becoming a good crew and worked in complete harmony with each other.

On the ground we were inseparable, and this seemed to be general with most crews.

In the early October we took part in a raid on Aachen, a round trip of just under five hours. Over the North Sea we encountered heavy electrical storms and, at times, especially when descending through heavy cloud, it seemed as though the lightning had picked us out for special attention.

'P' for Peter again returned intact but three other crews went missing.

We first encountered a German night fighter in the middle of October on an operation over Kiel.

Shortly after setting course from the target, Freddie in the rear turret called out, "Skipper, enemy fighter approaching dead astern." Immediately Wyn took evasive action, throwing the aircraft from side to side.

Freddie opened fire with his Brownings and, as the fighter came up on the port side, it opened fire hitting the port outer engine which caught fire. At this stage I commenced firing but neither of us appeared to score any hits.

Wyn activated the extinguisher and feathered the propeller, thus adjusting the angle of the blades to cause the minimum amount of drag on the wing. The fire was promptly extinguished and everybody kept a sharp look-out for the rest of the journey

The return on three engines took us longer than normal but we landed safely and taxied to where an anxious Russ was waiting. He inspected the damage and told us not to worry as he would have it all ready by the time we returned from leave.

Only one crew went missing on this operation.

The following day a maximum effort against Cologne was scheduled and we were asked to delay our leave by one day to take part.

Cologne, in the Ruhr, with its heavy concentration of anti-aircraft batteries was not considered a favourite target by the crews. The only thing in its favour was that it was a comparatively short trip of about four hours.

Take off was at 1900 hours and we got away on time. Crossing the North Sea our intercommunication failed and we had no alternative but to turn back. This abortive trip lasted just over two hours and did not count as an operation, but nobody was really disappointed at the early return.

We hung about the briefing room to welcome back the returning crews and the opinion was that it was a very tough target.

Three more crews were missing.

The following day with Bill Allen and Freddie Bourne I travelled down to London on my way to my parents home in New Malden.

The leave again was dull, my friends were still away and my brothers still in training to become bomb aimers. There was little to do and even my parents remarked upon my agitation. Being completely bored I returned to Graveley a day early.

While I had been away, three more crews had gone missing.

Our tenth operation was over Hamburg, and Oggie's last trip. "Looking forward to it Oggie?" we asked.

"You bet" he replied, "It's getting too hot for me."

By this time we were dropping flares and were among the first over the target area. The dropping point identified and marked out, we saw an aircraft coned by about eight searchlights. This was a most unenviable position to be in and the anti-aircraft guns pumped everything they had into the area of coning. The aircraft went up in a ball of flame.

An easy return was made from the target and, after de-briefing, Wing Commander Marks approached us.

"Well gentlemen, you have now finished your first ten operations and perhaps in the next day or two you can have your individual tests. On passing you will be qualified to wear the Pathfinder wings." He then congratulated 'Oggie' on completing his second and final tour.

The following day 'Oggie' left to go on leave and then on to a training station as an instructor. I did not really envy him as I thought that he would probably miss the excitement of an operational squadron and would have to settle down to a much more disciplined routine.

Chapter Four

My new role was that of wireless operator and the thought of being in a warmer part of the aircraft appealed to me, nor would I have to wear the heavy flying jacket and trousers so necessary in the mid-upper turret.

Our new gunner was named Bill Young and to avoid confusion with the other two Bills we decided to call him Billy. He was of short stature, came from Bedford and seemed quite a likeable character. He had no operational experience.

Our next target was a surprise, Turin. A complete change from Germany and, apart from a trip of about seven hours, mainly over France, it was regarded as easy. The most eye-catching part of the trip was flying over the Swiss Alps at 16,000 feet with Mount Blanc covered in snow and gleaming in the moonlight.

After crossing the Alps we dropped down to 8,000 feet to lay our flares. The opposition was very light indeed and caused us no problems.

On this operation Wing Commander Marks and his crew went missing.

The following day we took our Pathfinder tests.

The new squadron commander was Wing Commander Robinson from Kinloss.

On our twelfth operation we again raided Turin. I was now enjoying being at the radio desk and, when over the target, Wyn allowed me to stand up beside him and get a much better view of what was going on.

Operation thirteen was Turin again. On this particular operation Wing Commander Robinson 'borrowed' a crew from one of the captains. While making the run to lay flares they caught fire and, thinking that they were completely on fire, he gave the crew orders to bale out. This they did. However before the Wing Commander left the aircraft, the fire died out. He climbed back into the pilot's seat and took the aircraft back to base, an incredible achievement as he had to navigate and also, at intervals, change the petrol in the tanks.

The skipper of this crew was not very pleased when he learned what had happened to them.

A few days later, I and the others but excluding Billy, were advised that we had passed the tests and were qualified to wear the Pathfinder wings. Also Wyn was promoted to Flying Officer and the Sergeants to Flight Sergeant.

Jock Cruickshank applied for a commission.

Back to Germany again and this time Frankfurt. A long flying trip of over six hours and a very tough target. Several aircraft were shot down over the target area.

Sometimes news was received of crews that had been reported missing. Some had become prisoners of war and this was a prospect that I dreaded. I felt that I just would not be able to adapt to such an existence. We had recently attended a lecture given by a Flight Lieutenant who had been shot down near the Ruhr and had made his way back to England via France, Spain and Gibralter. From that time on I decided that, should Ie ever be shot down, I would make every endeavour to avoid capture.

Operations followed against Mannheim, Turin and Duisburg. After the Duisburg trip 'P' for Peter had nineteen bombs painted on its fuselage.

Christmas 1942 came and went and, due to bad weather conditions there was a lull in operations until the middle of January 1943 when a raid was made on the submarine base at Lorient.

Twenty trips had now been completed.

Further operations were carried out against Hamburg, Turin and Lorient. Over Hamburg we were coned by searchlights and the interior of the aircraft was lit up like daylight. After about six minutes of climbing, diving, twisting and turning we managed to escape. On the way back from Turin we were engaged by a night fighter that put out the inner starboard engine before turning away. The damage to the engine caused a loss of fuel and, on making an emergency landing at Beaulieu, only enough petrol for a further five minutes flying remained in the tanks.

We were then taken off operations to adapt ourselves to new radar equipment that had been supplied. At this stage, we also lost 'P' for Peter which was now due for retirement. We had completed twenty-three operations in this aircraft and were sorry to lose her.

On the twenty-seventh of March we were placed back on operations and issued with a new aircraft - 'X' for X-Ray. Two days later we took part in a raid on the 'big one' - Berlin.

Take off was at 2330 hours with an all round trip of about seven and a half hours. Over the target it seemed that all hell had been let loose; the flak was devastating! Within two minutes we saw our old friend Sergeant Wilks' aircraft explode in a ball of flame. The two crews had been firm friends for a very long time. They would be sadly missed.

There were very heavy losses that night and I myself saw nine aircraft shot out of the sky.

Twenty-four operations completed and half way through the tour.

There were no more operations until the fourth of April during which time Jock Cruickshank received his commission and Wing Commander Robinson was awarded a bar to his D.F.C. and promoted to Group Captain.

Operations were carried out on Stuttgart and Mannheim and, with twenty-six operations completed, We were regarded as the old lags of the squadron. Wyn was very careful to constantly remind us against complacency; there was still a long way to go.

A few days leave was granted and it was then that I was reunited with my two brothers who were about to commence operations. I was still very unhappy at the thought of three brothers being operational in the same command.

My eldest brother, Wilfred, seemed somehow to envy me for the number of operations that I had completed and bemoaned the fact that he had joined what appeared to be, an unhappy crew. This I knew, was a very bad start.

"Look Wilfred, it is very important that you all pull together and set aside your differences; you must act in complete harmony as one unit."

"Yes, I'm aware that this is true David and I suppose that somehow we shall manage to muddle through."

This attitude disturbed me to a great degree and it was with some relief that I learned from my other brother, Victor, that he had more confidence in his fellow crew members and was looking forward to commencing operations.

For once, I enjoyed my leave with my two brothers and did not return early to the squadron. This was to be the last time that we would all be together.

On return to the squadron I noticed new faces in the Mess and the absence of others. There had been further losses! Despite this reminder of what could lie ahead, I was pleased to be back. This was the life I had chosen and was more exciting than anything I had ever done before. With only another eighteen trips to go nothing could happen to us now - or so I thought.

A few days passed without operations and the normal squadron life went its usual way, relax as much as possible during the day with a few drinks in Cambridge of an evening.

Then, one day, the call for all crews to report to the briefing room. The general wish was for a quick one like Lorient so that we could get back into our stride. Anything but that bastard target Berlin.

The Skoda Works at Pilsen, Czechoslovakia, had been selected, a long trip of about ten hours. Take off was scheduled for 2120 hours and there would be a full moon, ideal for night fighter pilots.

While removing my flying clothes from the locker, I noticed the sealed letter addressed to my parents, this was the last thing I always noticed before closing the door. With any luck it would still be there at the end of the forty-fifth operation. Somehow, on this occasion, I had my doubts.

The usual routine was carried out. Coach to the aircraft, best wishes from the C.O., then all aboard. "Good luck Dave" and "See you tomorrow Russ, don't worry, we'll look after your plane for you."

Right on time we climbed away into the clear moonlight. Everyone settled down as normal. The only difference was that we did not like 'X' for X-Ray, it just didn't handle as well as the old machine.

Enemy coast crossed and a course for Pilsen set, Wyn levelled off at fourteen thousand feet and engaged the automatic pilot. I pulled aside the curtain from my window, the night was bathed in brilliant moonlight with not a cloud in sight. "Damn that bloody moon," I muttered. France lay below as we flew on.

Suddenly, a tremendous explosion. The aircraft bucked high into the air and fire blossomed on the starboard wing.

"I think we have been hit in the starboard outer engine" said Bill in a very calm voice.

"O.K. Bill, I have pressed the extinguisher button," - this from Wyn.

Another explosion and the aircraft rolled over and onto its back. "All crew bale out" called Wyn, "We have lost almost the whole of the starboard wing. - Good luck."

I had already clipped on my parachute and as dust and dirt fell from the floor, I was pinned in my seat. The aircraft went into a rapid spin and began to drop. There was nothing I could do. "So I'm going to die after all" I thought.

As I awaited death the aircraft righted itself and went into a dive. Suddenly Bill was beside me. Pushing aside the navigators seat he wrenched open the escape hatch door in the floor. The cold night air rushed in.

"Quick Dave - out!" Grabbing me by the arm he pushed me through the hatch and followed so quickly himself that we appeared to leave the aircraft pick-a-back.

Knowing that a tremendous amount of height had already been lost, I quickly pulled the rip-cord of my parachute. Almost immediately I felt a jolt and, looking up, saw the huge white silken canopy open above me. As the cold air rushed by my face I watched 'X' for X-Ray go into a steeper dive and crash with a tremendous explosion.

The ground rushed up.

Luckily for me the ground was grassy and relatively soft. I rolled over and over until I thought that I would never stop.

When my head stopped spinning, I stood up and unhooked the parachute. Relief flooded through me. I was still alive.

"Is that you Dave?" It was Bill Owen who had landed a short distance away. "You O.K.?"

I patted myself gingerly and agreed that I was indeed O.K. There I was, at about eleven in the evening, standing in the middle of a field in German occupied France, having fallen God knows how far through the air, and feeling perfectly and unbelievably calm.

"Look Bill, there is no point in looking for the others, let's get rid of our 'chutes and harness and get the hell out of here as soon as possible."

We rolled up our parachutes and hid them under some bushes in a small copse at the edge of the field. Just to make sure that we were not carrying anything that might incriminate us, we emptied our pockets. I found an old railway ticket, and Bill, two letters. These we buried. We were wearing identical uniforms. Battledress, thick roll neck jerseys and flying boots. In addition we had our escape kits.

Quickly we agreed to move as fast as possible away from the area, running for twenty paces and then walking twenty. In our estimation, Paris was about twenty miles due West, and there we should be able to obtain help. Remembering points from the escape lecture we set off, keeping clear of roads and into the moonlit French countryside.

"God" I thought, "I wonder what lies ahead?"

Chapter Five

Keeping mainly to the hedgerows, we walked and ran. We felt quite calm and hardly spoke. There wasn't very much to say. We both knew what we wanted and that was to get as far away as possible from the scene of the crash before dawn broke.

"See that village up ahead Bill, I think that is the best place to head for. We must get under cover shortly and, anyway, I'm just about all in."

There was no sign of life as we entered the village. We were walking now at an easy pace keeping close to the walls and buildings. Just ahead, we saw a small church. "How about in there?" I asked. Bill agreed that it seemed the most likely spot and cautiously we entered the graveyard and made for the church door. Gently I turned the handle - it was locked.

"Blast! Let's get into that corner of the graveyard out of sight and wait awhile." We made our way quietly to the corner and settled down. Our clothes were soaking wet.

"What do you think happened to the rest of the lads Dave? I didn't see any other parachutes come out of the plane. Billy and Freddie could have baled out because Freddie could turn his rear turret and roll out and Billy could have got out of the entrance door quite easily."

This to me, appeared to be a reasonable assumption and I went on to speculate on the chances of Wyn and the others.

The early morning chill struck through our wet clothing. The first light of dawn appeared and we began to hear footsteps in the street outside. Hidden as we were by the high churchyard wall, we could not see out into the street, nor could we be seen ourselves. Feeling secure in our present position we dozed off until the sound of a passing vehicle bought us back to reality.

Bill looked at his watch. "Hell Dave, it's nine o'clock."

People were now walking and talking in the street. Suddenly an elderly woman appeared on the footpath from the main gate. Slowly she walked, looking neither right nor left until she reached a grave. She stood for a moment looking at the stone oblivious to her surroundings and then knelt down and began to tend the grave.

As I spoke French, I decided that I would approach her. Bill crossed his fingers. So as not to alarm her unduly, I approached her in a half circle, the dew covered grass soaking my boots. As I crossed her line of vision she stood up, fear slowly dilating her eyes.

"Good morning Madame, I wonder if you can help me?"

"You are R.A.F." She replied, seemingly horrified.

"Yes, my friend and I were shot down last night and we need help."

Quickly for her age, she bent down and started collecting the small tools she had been using. "You must go away from here, there are many Germans stationed in this village. It is very dangerous for you." Hastily she packed away her tools.

"Please, you must help us." I pleaded.

"No, no, there are many, many Germans, I can do nothing for you. I can only promise that I shall not tell anyone that I have seen you." She scurried away leaving me before I could utter another word.

Bill was not at all happy.

"She'll shop us, I know it." I thought about this and said, "No, I don't think so, not from the way that she spoke. She was just frightened, that's all."

For a while we remained crouching in the corner unsure what to do next. After what appeared to be an age, a figure, who appeared to be the local priest, entered the yard and approached the church door keys in hand. After our recent rebuff, we were reluctant to make a move, although by now, we were both weary and hungry.

"We'll wait a few moments and then go in" I decided.

Slowly, we made our way to the now open church door. At first sight the church was empty. "This way Bill, to the vestry." I led the way, gave a gentle tap on the door and, without hesitating, walked in.

The priest turned round and looked at me seemingly unperturbed.

I cleared my throat nervously. "Good morning Father" I said, "I speak French a little and I will be able to understand you if you speak to me slowly."

The priest approached hand outstretched.

"Monsieur, I see that you are both of the R.A.F. and, as you are now in the house of God, for the time being you are safe." Gently, in turn, he embraced both of us.

I recounted the happenings of the previous night and told him about the woman in the churchyard. He apparently knew of her and was able to assure us that their was no possibility of her informing the Germans. "However," he said, "It is too dangerous for you to stay here too long, there will be search parties out and I, myself have seen many R.A.F. taken by the Germans in this area. As it is, you are both wet and cold, I will leave you now and lock the door. Within one hour I will return with blankets and food. You may rest here all day but tonight you must depart." He bade us farewell for the moment and went out locking the door behind him.

The sun streamed strongly through the heavily leaded windows making the tiny room uncomfortably warm. We two fugitives removed all our clothing and placed them where the sun could dry them.

As promised, within an hour the priest returned, again locking the door behind him. "All is quiet in the village, but please keep your voices down." From one suitcase he provided blankets and from another, bottles of red wine, bread, cheese and cold chicken. "Eat now and rest my children. When I depart I will take all your clothing and dry them at home in front of the fire.

"Thank you Father, you are very kind" I said. The priest departed once more taking our clothing with him. From him we had learned that the village was 'Villiers-au-Tours' and that, when he returned in the evening he would give us directions for our next move.

Warmly wrapped in blankets and replete with good food and wine, tiredness soon overcame us. I dozed fitfully, between snatches of sleep I could not help thinking of my parents receiving the telegram telling them that I was missing. Also I thought of other members of the crew and wondered how they had fared.

Afternoon turned to evening, evening to dusk. Unable to sleep further, we discussed our chances and agreed that, provided we were careful, there was a good chance of succeeding. Closing the curtains tightly we lit an oil lamp and checked the escape kits. Everything that should be there was, indeed there, much to our delight and surprise. Carefully we examined the silk map of France and found our present location. Paris was, approximately, twenty miles away.

We formulated a plan. We would make for Paris and hope to meet the resistance along the way. We would travel by night and sleep by day. We would avoid roads and use fields as much as possible. At the moment we would have the moon to light their way.

At almost eleven o'clock the door was again unlocked and we moved quickly behind it. Again it was the priest, this time accompanied by a very much younger man.

"Good evening gentlemen, this is Pierre who has kindly helped me carry these parcels." The parcels contained our clothing, now completely dry. We quickly changed into our uniforms and awaited instructions.

The newcomer spoke.

"English gentlemen, the Father here has been of very great assistance to you but, he is an old man and very frightened. There has been a German army search party in the village today but they have now departed. I regret that it is very necessary that you leave here as soon as possible. I have here a bottle of wine for each of you, also cheese and bread. That is all we have been able to manage."

I thanked him.

"You both have been very kind and it would be unfair of us to continue to be a danger to you, naturally we shall leave as soon as you wish." I then showed him the map and asked for his suggestions as to our next move.

Pierre studied the map intently. Pointing with his finger he said,

"Here is the village of 'La Mal Maison', there is no German garrison there and it is possible that you may be able to meet up with the resistance. Unfortunately I have no contacts in that place." He then requested that we leave at midnight and pleaded that should we be caught, we would not divulge who had helped us. Assuring him that he need have no fears in that direction, we departed with the request that all doors be closed on leaving and them expressing their hopes that all would go well for the rest of the journey. I was never to see them again.

Checking the map we found that 'La Mal Maison' was about nine miles away and we decided to move out at a walking pace in fifteen minutes time. Having rechecked our belongings, at the appointed time we turned out the oil lamp and passed into the church. Before leaving I made my way to the altar and gave thanks to God for having spared our lives and asked for strength to face what may lie ahead. We walked out of the church into a night of uncertainty.

The moon shone brightly and, following the directions given by Pierre, we soon found ourselves out on the country road. As we could see so far ahead we decided against our earlier decision and kept to the road. On and on we walked, stopping for about five minutes at the end of each hour. By four o'clock we were tired, thirsty and hungry. We decided to give it another hour and, if by then we had not reached 'La Mal Maison', we would admit defeat and rest up for the remainder of the day.

On we trudged for another hour and, in the first light of dawn, saw a wood about one mile off the road. Crossing two fields we entered the wood and selected a spot where there was a commanding view of the road.

Gathering bracken we made makeshift beds, drank some wine and hungrily attacked the bread and cheese. The inner man satisfied, we stretched out and rested. Our rest was shortly disturbed however by the sight of a German troop carrier containing six soldiers moving slowly down the road. It did not stop but it was a disturbing thought that it was the hunter and we the quarry.

There could be no sleep for us for the rest of that day and, with the food demolished, we had to make do with concentrated food tablets. These tablets made us feel as though we had partaken of a substantial meal.

We surveyed the situation.

"We'll have to get some help soon Bill" I said, "I feel so bloody tired and stiff." Bill agreed and, while idly viewing the scenery, suddenly was sure that he could see a large village about two miles away. We agreed to move out again at midnight, hide near the village until daylight, and then ask for help.

At midnight we moved slowly off in the direction of the village. After about forty-five minutes we reached the outskirts and, just off the road, saw a farmyard with a Dutch barn. Quietly we entered the farm and into the barn. Inside we were delighted to find a large quantity of hay into which we climbed and covered ourselves. The gentle warmth enfolded us and we were soon asleep.

Bill nudged me. "Wake up David, believe it or not we are still alive." I peered out from the hay, it was dawn. "Let's hope it's 'La Mal Maison'" I said. We finished the remainder of the wine.

I decided to call at the farmhouse. It was a chance I just had to take.

"If I'm carted off Bill, you are on your own old son." Bill ruefully agreed that this was so and crossed the fingers on both hands.

Wearily climbing out of the hay, I crossed the farmyard and up to the house. Gently I knocked on the door. From inside, footsteps approached and the door opened. On the threshold stood a very elderly and obviously surprised man.

I hesitated. "Good morning Monsieur, I am an R.A.F. flyer who was shot down two nights ago." It was a brief, bald statement, but I could think of nothing further to say.

The man's face lit up with a beaming smile. Very suprisingly flinging his arms around me he said,

"You are among friends dear boy, please do come in." I was led into the farm kitchen where, before a large glowing fire, sat an elderly lady in an upright chair. "This is Madame Pondin" said the man by way of introduction. I offered my hand. Taking my hand, the lady drew me towards her and gently kissed my cheek. "I know that you are Royal Air Force and that God has sent you to the right and safe place; you are amongst friends." I explained that my friend was still in the barn and was promptly sent to fetch him in for something to eat.

Bill was greatly relieved that all was well and uncrossed his fingers.

Once back inside the house we were told that there were no Germans in the village and only about once a week did they have a routine army patrol. The Pondins explained that both their sons had been in the French Air Force and were at present undergoing forced labour in Belgium.

After a substantial breakfast of hot coffee, white bread and fried eggs we were invited to wash, shave and then sleep for as long as we wished. I had to constantly tell Bill what was being said. We could not believe our good luck

Monsieur Pondin explained that they had many friends in the village who would help us on our way, but he could not be sure at that time how long we would be staying before arrangements could be made to move us on.

Having washed in warm water we were shown an enormous bed with a large quilt awaiting us. In no time we were fast asleep.

It was dark when I awoke. I gently shook Bill and asked him the time. Bill went to the window to look at his watch. It was ten o'clock at night, we had slept for twelve hours. Deciding that we were hungry, I went downstairs and, hearing voices behind the kitchen door, knocked gently.

The door was opened by Monsieur Pondin.

"Good evening David, have you and your friend slept soundly?" I replied that we had indeed and asked for permission for Bill and myself to join them. Permission was readily given and soap, towels and hot water together with new dry clothes were taken up to our room. We were also told that all was well and that there was nothing to worry about. Our uniform pockets had been emptied and the contents were safe downstairs. The uniforms had been burnt during the day.

Shortly Madame Pondin arrived carrying a small bottle in which, she explained was a liniment which, when well rubbed in, would ease away any remaining stiffness. She, and her husband then returned downstairs telling us to follow when they were ready.

Having washed, rubbed in the liniment and donned the new trousers, shirts and socks, we felt very much better. We went downstairs and entered the kitchen. There were other visitors, two elderly men who were introduced merely as Gavin and Lubeck.

As introductions were being made Madame Pondin arrived with food. An enormous omelette, a large dish of mashed potatoes, bread, butter, cheese and wine were placed upon the table. We needed very little urging before heaping our plates.

Whilst we were eating, I was asked to recount our story so far. I talked for about an hour without interruption. The story told, Monsieur Pondin said, "You have told that well David, now I will tell you of our plans. Tonight a few trusted friends will join us and we will have a little party to celebrate your arrival. It will make a change for us and I still have some decent Champagne left."

I explained to Bill that there was to be a party with Champagne in our honour and he was delighted, although he was just a little disappointed that no firm details had yet been given for our next move.

People started to arrive, they were of various age groups but all pleased at meeting us. Corks popped and the wine flowed, everyone was in a party mood. I needed to frequently lubricate my throat as it was thirsty work talking in French and then repeating everything again in English for Bill's benefit. The party went on gaily until about two in the morning by which time I began, unwillingly, to yawn. Madame Pondin noticed this and suggested that, if we wished, we should retire. With handshakes all round we made our apologies and retired.

When we awoke the next morning the sunshine was streaming through the windows and, to our delight, their stiffness was gone - the liniment had worked. Only problem was - we both had dreadful hangovers! Wincing, I knocked hard on the bedroom floor and, within minutes Madame Pondin arrived with two very large cups of steaming coffee.

She tilted her head and eyed us smilingly.

"I imagine your heads are a little sore this morning, yes?" Like two small schoolboys caught committing a minor misdemeanour, we agreed that this was so. She nodded understandingly and told us not to worry, the coffee would soon pick us up. As I said, "She ought to know - she was right about the liniment!"

After washing we both went down to a huge 'English' breakfast of bacon, eggs, home made bread and butter. With raging thirsts we drank cup after cup of coffee.

As she cleared up the debris, Madame Pondin warned us only to go outside to the toilet and, on no account, wander about. We continued to sit at the table and talked of our good fortune so far. Suddenly the door burst open and Monsieur Pondin with a man from the previous night's party rushed in.

"Quick David, you and Bill must follow me, we must hide you outside. There is going to be a search of the village."

We leapt to our feet and followed him outside. Madame, quick for her years, moved swiftly up the stairs to remove all traces of occupancy from the bedroom.

Monsieur Pondin led the way to a large wood about a mile and a half away. For his age he was very agile. We moved well into the trees and to a position where we could keep watch on the road.

There we stood, backs bent, hands on knees, panting and coughing. Monsieur Pondin straightened and looked about him.

"You will be safe here, but you may have to stay for a few hours yet. If you have to stay longer I will have food bought to you." He jerked his head in the direction of the village. "Back there the local Gendarme told me that a large German patrol is on its way to search the village, house by house. We will keep a watch on their movements and, if necessary, we will move you again."

Cautioning us to stay exactly where we were, he moved off back in the direction of the village.

We sat down, knees drawn up to chins, to watch the road. This we agreed was our first fright since we had arrived in France and that we should get used to the idea that it could happen again.

From time to time villagers arrived to keep us company. They told us that the patrol had arrived and were searching the houses for two British airmen. This puzzled me. "Bill, why only two?" Bill shrugged. "The others must have been caught."

For the first time I began to have doubts about the safety of the other crew members. Whatever happened, I had no intention of being taken prisoner. The idea of being caged up was abhorrent to me.

It was not until dusk that we were taken back to the village, this time to a house of a man called Derso. We were not to see the Pondins again. Derso spoke very little, but appeared to be full of quick efficiency. He told us to rest well as we were to leave the following morning.

In the morning after breakfast, bicycles and two suitcases were produced. The cases contained soap, razors and spare clothing. In addition we still had our pandoras and escape kits. Our only instruction was to take the bicycles and cases and follow our guide.

The parting was brief, Derso merely slapped us each on the shoulder and grunted "Bon chance."

Chapter Six

For nearly two hours we cycled through the spring sunshine until arriving at a village, German soldiers were strolling about the main street enjoying the spring air. The guide wheeled over to a small house opposite the railway station and dismounted. Beckoning us to follow him, he walked round to the back of the house and in through an open door.

"Monsieur David, you are in good hands, this is the home of Monsieur Constant." Constant was a short man of about forty with very dark hair. His greeting was warm and emotional. Placing his arms about us, tears in his eyes, he said.

"You are very welcome in this house. This village has a German garrison but your safety is guaranteed, you see the German Commandant, Major Uttner, is a friend of mine and often calls here. If he calls I shall introduce you and you will have no need to be nervous, he is anti-hitler and anti-this war."

I translated this disturbing statement to Bill and we agreed that there had no choice but to trust our new host.

Our stay proved quite enjoyable, we each had our own bedroom and, after breakfast, would sit at the front window and watch the train arrivals and departures. We even formulated nicknames for the German soldiers who regularly passed by. We were pleased to see only army personal and no Gestapo. By this time my French had improved immensely and could understand everything said to me without further clarification.

After only two days, Paul Constant announced that the German Major was to pay a visit. Again he told us not to worry, everything would be alright. We had a good supply of strong French cigarettes and this announcement caused us to smoke incessantly.

That evening a chauffeur driven car drew up outside and quite shortly after Paul entered the room with a uniformed German army officer.

"Gentlemen, may I introduce Major von Uttner?"

We both stood up. The Major, hat under armpit clicked his heels and said in perfect English,

"Good evening gentlemen, what are your names please?"

I introduced myself and Bill as Bradley and Allen. The Major nodded. "Delighted, I know about you both but you have no need to fear me. I believe that it is only a matter of time before that madman Hitler destroys Germany and all of us with it. Please rest assured that your presence here is in no way an embarrassment to me. However, at all times you must avoid the Gestapo. If they catch you in those clothes you will be questioned and shot, so be very careful.

It transpired that the Major had been educated in England and had a degree from Oxford.

The Major's command of the English language was impeccable and it was a great relief to me not to have to speak French all of the time. As for Bill, he was delighted - at last he had someone to talk to!

Red wine was served and von Uttner told us something of his life. He had joined the German army as an Officer Cadet in 1937 and had taken part in the invasion of Poland, from there he had joined the occupation forces in Holland and later, France. He was convinced that Germany should have invaded England after the fall of France when there was virtually no opposition and blamed their failure to do so on Hitler. England would have been beaten but no, Hitler preferred to wait and then made the colossal blunder of invading Russia. Von Uttner confessed to being completely disillusioned about the whole business. He emphasised that he had never committed atrocities nor would he allow troops under his command to do so.

Bill had listened to all of this in complete silence. Then as the Major prepared to enlarge on military conduct in general, he leaned forward and said, "Maybe so, Major but how would you have behaved awhile back had you been in an occupation army in England?"

The Major's faced flushed and he stood as though to leave.

"I am an aristocrat and an officer of the German army. My behaviour would always have been that of a gentleman."

I stepped in to defuse this new situation.

"Major, I accept all that you say" I said, "Now may we please discuss with you our present situation?"

The Major refused to be drawn although he did resume his seat. He stated emphatically that he could be of no assistance but reassured us that their meeting with him would have no effect on our future safety. He wished us the best of luck and quickly reminded us never to mention the fact that they had met. From that moment the war was quickly forgotten and, as the wine flowed, conversation turned to other topics. The Major finally bade us farewell in the early hours of the morning.

The following day Paul told us that he had to go out to keep an appointment. After he had left and having nothing better to do, we took up their regular vigil at the window and watched the world, and the trains, go by. Shortly before mid-day, Paul returned and told us to pack at once as he was going to take us by bus to Laon.

"On the bus I will pay your fares but do not speak to me. If, for any reason the bus is stopped, do not ask questions, just ignore me. When we arrive in Laon follow me at a close distance and I shall lead you to a doorway. Once there, go in and up the stairs. At the top of the stairs you will find a door marked 'B'. Knock on the door and someone will let you in. I shall bid you farewell here and wish you good luck on your journey to England. When you are there, please tell them how we are trying to help."

Swiftly we packed our meagre belongings and returned to Paul who gave us a final embrace, again with tears in his eyes.

Past the station we walked, Paul slightly ahead, until coming upon a stationary single decker bus. We entered, sat down and pretended to sleep.

The road was bumpy and the journey seemed endless. Eventually we entered the outskirts of what seemed to be a sizeable town. Everywhere there were German troops and it looked as though it might be a garrison town. The bus stopped and Paul rose from his seat, myself and Bill quickly behind him. After a short walk we came to a building and a doorway at which Paul stopped. We knew that there would be no further farewells. Paul just smiled, nodded, and walked away.

Bill led the way in and up a rickety stairway. At the top was a door marked 'B'. He tapped quietly on the door. No answer.

He tapped again. No answer. We felt an icy feeling of fear; supposing no one answered, what would we do here in a foreign town with no friends or contacts and no papers. There was nothing to do but wait. Just as I was going to speak, the door slowly opened and a disembodied voice from within said in English, "Enter".

Slowly we edged into a sparsely furnished room equipped with only a table, four chairs and a threadbare carpet. A middle aged man stood holding the door handle with one hand and a revolver in the other. He closed the door quietly and addressed us in halting English.

"Your names please?"

"David Bradley and Bill Allen. Who are you?"

He gave a gesture of impatience.

"I am asking the questions, give me the name of the man who bought you here?"

"Paul."

"What was the name of the village before you came to Paul?"

"La Mal Maison."

He smiled and placed the revolver in his pocket. "My greetings to you both. Just call me Seraglio. Please excuse my bad manners but we have to be very careful. You will eat here now and later you will be taken by car to another place. We must keep you moving all the time. Ask no questions, just do as I tell you and you will be safe. Now please sit at the table."