|

|

|

Those known to have served at RAF Skellingthorpe during the Second World War 1939-1945. - Alford Bernard William. F/Sgt.

- Aston Ron. Flt.Lt

- Aston Ron. Flt.Lt

- Austin Derrick. Sergeant (d.8th Jul, 1944)

- Battersby. Ronald . Flight Sergeant

- Beresford A. G.. F/Sgt.

- Bishop James Douglas. P/O (d.8th Jul 1944)

- Blakemore E. J.. P/O

- Boakes Edward . Flight Sergeant

- Brown Frederick. Sgt.

- Buchan David McDougal. Sgt.

- Campbell Jack.

- Cole T. B.. Sqd Ldr.

- Cook Michael Arthur. F.Sgt. (d.6th Nov 1944)

- Copson D.. Sgt. (d.22nd Jun 1944)

- Corewyn. William . Flying Officer

- Craig Robert. Flt.Sgt. (d.25th July 1944)

- Craven J.. F/O.

- Cunningham Robert Norval. (d.11th May 1944)

- Dane William Frederick Selwood. WO.

- Darby William. Sgt. (d.6th Nov 1944)

- Deaville Aurther Kenneth. Flt.Sgt.

- Douglas. John . Sergeant

- Dowling Ralph Andrew. Flt.Sgt. (d.6th Nov 1944)

- Dunkelman George Amos. P/O (d.6th Nov 1944)

- Dunkleman Fred. Sgt.

- Earl. Peter . Sergeant

- Elliott Newman Walter. Flt.Sgt.

- Ferris George .

- Grantham William Edwin. F/Lt. (d.8th July 1944)

- Green Albert William. Sgt.

- Hannah N.. P/O

- Harper Robert Noel. Sergeant (d.8th Jul 1944)

- Higgins George Albert. Sgt. (d.8th Jul 1944)

- Hill Gordon Leslie. Flt.Sgt. (d.26th July 1943)

- Hopkins Frederick Randall. P/O (d.8th Jul 1944)

- Horning Fred. Sgt.

- Horning Frederick Arthur. F/O (d.6th Nov 1944)

- Ingram Kenneth Herschel Callender. F/Sgt. (d.2nd Oct 1944)

- Jackson Clifford. F/Sgt. (d.8th Jul 1944)

- James Sidney . Flight Sergeant

- Laidlaw Alain. P/O

- Lane J. F..

- Law Francis Reginald. Sgt. (d.22nd February 1942)

- Lloyd Edgar Charles Prytherch . Sgt. (d.8th Jul 1944)

- Manning . John. F/Sgt

- McCallum Robert. W/O

- McConnell Victor. F/O. (d.11th Apr 1944)

- McCray David William. F/Sgt. (d.17th Dec 1944)

- McDonald H. S.. F/Sgt.

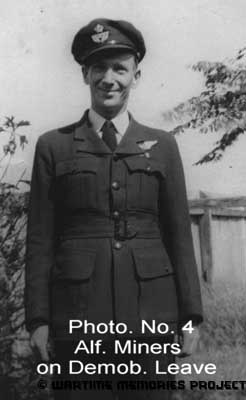

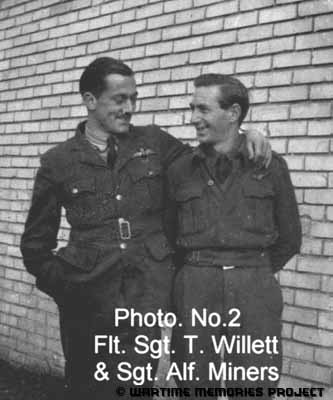

- Miners C. Alf. Sgt.

- Motriuk Stanley Arcadie. W/O (d.8th Jul 1944)

- Nash MID. Reginald Morris.

- Noren Peter Oliver Kenneth. Flt Sgt. (d.8th Jul 1944)

- O'Connor Charles Joseph. F/Sgt. (d.8th Jul 1944)

- Packard S. E.. F/Sgt.

- Poole David John. Sgt. (d.24th Dec 1943)

- Rennie Robert .

- Rennie Robert Edward. F/O (d.6th Nov 1944)

- Richardson. Richard . Sergeant

- Ross Robert John S.. Sgt.

- Scott C. J.. Sgt. (d.30th Apr 1942)

- Shorter Frederick Henry. Sgt. (d.22nd Jun 1944)

- Spencer Hubert Arthur. Flt.Lt

- Stenner Lester.

- Stirling Eric John Walter. F/Sgt. (d.8th Jul 1944)

- Terris George Thompson Gilbert. F/O (d.6th Nov 1944)

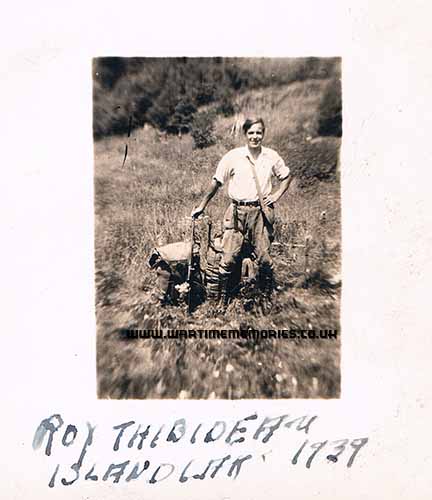

- Thibedeau Roy Frederick. P/O (d.31st Mar 1944)

- Tucker George Henry. Sgt. (d.8th Jul 1944)

- Tweedale Frederick. Sgt. (d.4th Oct 1943)

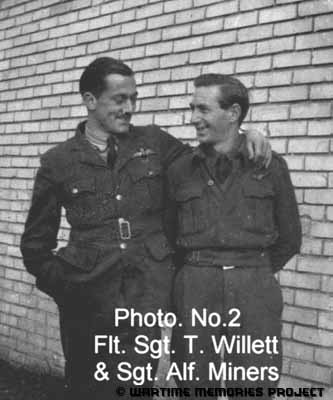

- Willett DFM.. S.. F/Sgt.

- Willett Tim. Flt. Sgt.

- Williams D. A.. Sgt. (d.30th Apr 1942)

- Wise Geoffrey Norman. F/Sgt. (d.12th Sep 1944)

The names on this list have been submitted by relatives, friends, neighbours and others who wish to remember them, if you have any names to add or any recollections or photos of those listed,

please

Add a Name to this List

|

|

|

The Wartime Memories Project is the original WW1 and WW2 commemoration website.

Announcements

- 1st of September 2024 marks 25 years since the launch of the Wartime Memories Project. Thanks to everyone who has supported us over this time.

- The Wartime Memories Project has been running for 25 years. If you would like to support us, a donation, no matter how small, would be much appreciated, annually we need to raise enough funds to pay for our web hosting and admin or this site will vanish from the web.

- 19th Nov 2024 - Please note we currently have a huge backlog of submitted material, our volunteers are working through this as quickly as possible and all names, stories and photos will be added to the site. If you have already submitted a story to the site and your UID reference number is higher than

264989 your information is still in the queue, please do not resubmit, we are working through them as quickly as possible.

- Looking for help with Family History Research?

Please read our Family History FAQs

- The free to access section of The Wartime Memories Project website is run by volunteers and funded by donations from our visitors. If the information here has been helpful or you have enjoyed reaching the stories please conside making a donation, no matter how small, would be much appreciated, annually we need to raise enough funds to pay for our web hosting or this site will vanish from the web.

If you enjoy this site

please consider making a donation.

Want to find out more about your relative's service? Want to know what life was like during the War? Our

Library contains an ever growing number diary entries, personal letters and other documents, most transcribed into plain text. |

|

Wanted: Digital copies of Group photographs, Scrapbooks, Autograph books, photo albums, newspaper clippings, letters, postcards and ephemera relating to WW2. We would like to obtain digital copies of any documents or photographs relating to WW2 you may have at home. If you have any unwanted

photographs, documents or items from the First or Second World War, please do not destroy them.

The Wartime Memories Project will give them a good home and ensure that they are used for educational purposes. Please get in touch for the postal address, do not sent them to our PO Box as packages are not accepted.

World War 1 One ww1 wwII second 1939 1945 battalion

Did you know? We also have a section on The Great War. and a

Timecapsule to preserve stories from other conflicts for future generations.

|

|

Want to know more about RAF Skellingthorpe? There are:30 items tagged RAF Skellingthorpe available in our Library There are:30 items tagged RAF Skellingthorpe available in our Library

These include information on officers, regimental histories, letters, diary entries, personal accounts and information about actions during the Second World War. |

|

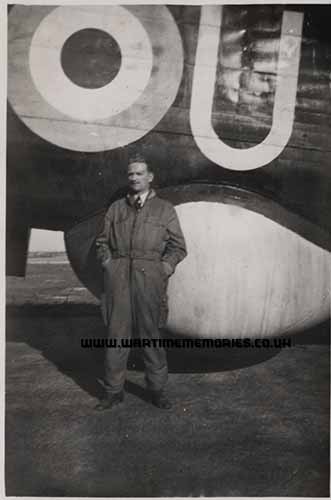

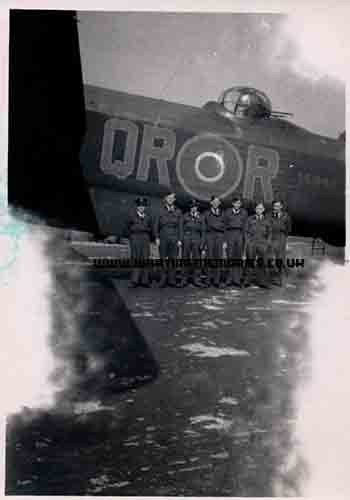

Flt. Sgt. Tim Willett pilot 50 Sqd F/S Willett was pilot of Manchester L7516 VN-N which was shot down on the 20th of April 1942 flying from RAF Skellingthorpe. They landed on tidal mudflats on the island of Sylt, Germany.

The crew were:

- F/S S.Willett DFM

- F/S S.E.Packard

- P/O N.Hannah

- F/S H.S.McDonald

- Sgt C.A.Miners

- Sgt D.A.Williams

- Sgt C.J.Scott

|

Sgt. C. Alf Miners 50 Sqd

In 1941 I trained in the Australian Empire Air Training Scheme as a Wireless Operator/Air Gunner and on completion was posted to the embarkation depot in Perth, Western Australia, where I discovered I would be posted to Singapore. A few days later we were told that a number of Lockheed Hudson aircraft which were to be sent by the British to Singapore for our use could not be spared and consequently we were to travel to England.

The first part of our travels was under first-class conditions on an American passenger liner, the Maraposa, where I was fortunate to be allotted a single, self-contained cabin on the Promenade deck, much to the envy of all the troops. This ship was, of course, travelling under peace-time conditions and the food was quite unbelievable. The ship called at several ports on the way including Auckland, Fiji, Pago Pago and Honolulu. At the last named we were met by some of the local ladies who had brought their cars in order to take us on a tour of the island.

At one of the beaches we surprised a soldier who was supposed to have made himself invisible and prepare for an invasion. I did have the opportunity to examine a Garrard semi-authomatic rifle which I had not previously seen. The American Air Force put on a show for us with a full squadron of 'Bell Air Cobra' fighter aircraft which were well in advance of those we had in Australia. I should mention that this incident happened only a few weeks before the attack on Honolulu by the Japanese.

Our first port of call in America was Los Angeles where we were taken on a tour of Warner Brothers' film studios. After touring the studios we were given drinks and cigarettes by young starlets. We watched Bette Davis at work on a picture as well as other performers whose names I have since forgotten.

We re-embarked and travelled to San Francisco where we boarded a train for Vancouver. We made a number of stops and at most of them there were local inhabitants gathered at the level crossings, apparently to cheer us on. Although conversation was carried out at high volume, it was a very friendly interlude. The reception was at all times very enthusiastic and we all felt that there was a strong bond between Americans and Australians. The journey was quite enjoyable and the type of country varied a lot, unlike our Nullabor Plain.

After arrival in Vancouver we were embarked on the Canadian National train. I was very impressed with the size of the locomotives which were designed to haul their trains across the Rocky Mountains. During this trip we travelled almost exclusively by night and we were given the days to see what we could of Canada. The highlight was in Ottawa where, to secure better photos, we entered the tallest building we could see. This building we discovered was a Government office housing the Department which dealt with the inhabitants of the northern ice-bound regions. We met a Department officer who went to a great deal of trouble to explain the difficulties and the way in which they tried to overcome them. The places at which we stopped which spring most easily to mind are Jasper and Toronto which are quite beautiful. We travelled right across Canada on the train which had the American style Pullman sleeping cars, the journey taking about a week.

At Halifax, the end of the line, we boarded a troop ship, The Warwick Castle, a vessel of 20,000 tons and which was cleared to join a 20-knot convoy. My good fortune still held for this ship had not been converted to the usual troop ship but still had four-berth cabins. We were provided with a strong escort which included a light cruiser and a number of destroyers. We saw little action on the Atlantic crossing although when we counted the ships each morning there appeared to be some missing. We saw a demonstration of the ability of these escort ships when a warning of a submarine attack was given. The sight of these ships speeding around making rapid, sharp turns and throwing depth charges was something I will never forget. On this day the swell was described as 'moderate' but I think sailors are very conservative. I did not discover whether these depth charges caused any damage to the submarine. Over one day and night we encountered a severe gale when the sea swamped the boat deck making the biggest waves I have ever seen.

On arrival in England at Greenock, we disembarked and travelled by train to Bournemouth on the south coast. On the first night a small bombing raid was mounted by the Germans and although only a small number of aircraft was involved, some damage was inflicted and particularly to one of the nicest hotels. Our training did not include instruction on what to do in an air raid so we went to an air-raid shelter which seemed to be overcrowded and, I thought, the reception was somewhat hostile so we decided to go to the nearest hotel where we spent a pleasant evening despite the 'dressing down' I received for being too slow to close the blackout covers over the door. For some reason the ARP (Air Raid Precautions) were concerned this small light could be seen from the enemy aircraft and would precipitate an enemy attack.

I was posted to the Operational Training Unit near Doncaster and then to the squadron at Lincoln which, unfortunately, was equipped with 'Manchester' aircraft. We flew operations one night and had the next day at leisure. In order to perfect the methods to be used in the planned '1000 bomber raids' it was decided to send 250 aircraft per night for two nights consecutively on each target which were the cities of Lubeck and Rostock which had a ball-bearing factory and submarine pens respectively.

On the first of these raids on 28 April, 1942, we were instructed to attack Rostock at 12,000 feet and 'glide' bomb at 10,000 feet. I should mention that the 'Manchester' bomber could not reach a higher altitude so most other aircraft were flying at twice our height. After releasing the bombs we experienced a major explosion some distance below us and we flipped over on to our back. The pilots were successful in gaining control and righting the aircraft which was quite close to the ground as most of the crew agreed they felt heat from the fires in the city. Later discussion arrived at the belief that the explosion was a shell from a demounted cannon from one of the 'pocket' battleships. After this, the trip back to base was uneventful and we reached our squadron in Lincoln. The aircraft was fairly badly damaged, especially at the rear, by light and medium anti-aircraft fire. By some miracle the rear-gunner was not hit. On touchdown, however, a 500lb bomb, which had apparently been hung up on the bomb rack came out of the bomb bay from the starboard side and ran along the ground beside us for some time before it veered away. Fortunately, it did not explode.

Two nights later, on 30th April, 1942, we were instructed to lay mines around the 'pocket' battleship bottled up in Kiel harbour. This entails flying at an altitude of 500 feet at 150 miles per hour, straight and level. As I remember, this night was lit by a full moon and everything, including our aircraft, seemed brightly illuminated, which gave an uneasy feeling of insecurity. In addition, our instructions lead us further into Germany than any other bomber on that night which meant that for several hours we were the only intruders over enemy territory. As we proceeded on our way back to base it was discovered that one of the 1600 lb mines had hung up on the bomb rack and was still with us. The normal manoeuvres did not dislodge it so it was left in the bomb bay.

As we approached Denmark we were attacked by an ME 110 night fighter from below, which meant he was not seen and the first indication was a burst of gunfire. I was flying in the mid-upper gun turret on this night and a burst of cannon fire entered the lower portion of the turret, under my left arm and out through the Perspex in the top of the turret. I then saw gunfire at the rear of the aircraft and decided it was aimed at the rear gunner and as I saw no answering fire concluded he had been hit. I then requested the wireless operator to investigate.

I was able to fire a burst at the attacker who was below us and travelling in our direction. Unfortunately, the downward angle of fire was too steep and the guns jammed. I had further opportunities later the last of which was when the enemy appeared to have broken off the attack and went under us from right to left. The German rear gunner was still firing and as my gun came to bear, I fired and his firing stopped. My assumption was that I had made a hit.

I then saw that our port engine was on fire and although the pilot took all available action, including trying to feather the propeller, nothing worked and the fire increased. Due to enemy action our landing lights were activated thus lighting up the aircraft like a beacon. These were later extinguished and the order to abandon the aircraft was given. In order to vacate the turret it was necessary for me to step on to the arms of a chair beneath me and then get out. However, my foot slipped and I fell and was caught by the release buckle of my parachute harness on the floor of the turret and was swinging in mid-air. I managed to free myself and fell, fracturing my collarbone. My parachute was packed beside the door at the rear of the fuselage but the fire had beaten me to it thus rendering it useless. I then checked that the IFF radio

(Identification "Friend or Foe") had detonated. This occurred as I looked and suffered some burning to my face.

By this time, the pilot had decided to land on the sea, which he did but was unable to pass on his decision to the rest of the crew as the intercom was not working. Following the decision to bail out, the front gunner and second pilot had attempted to open the escape hatch in the bomb aimer's position. Although it was jammed it eventually opened and the front gunner jumped. Unfortunately, the aircraft had descended to about 100ft and he was killed instantly. The second pilot then dived and swam to the side. We had landed on a sandbank but when the aircraft settled down it was found that he was trapped by the foot. The surviving crew members climbed out through the astrodome on to the starboard wing and between us we managed to free him and get him on to the wing.

As we could still see the searchlights operating on the shore it was an indication that we may be close enough to be able to walk there. The water we were in came up to my neck and when I tried to inflate my 'Mae West' lifejacket I was unsuccessful. The jacket was shown to me the next day by a German guard and had two bullet holes running parallel to my body. There was no life raft in the aircraft so our position looked a little precarious.

We started to wade and I tried to help the injured pilot but as his left leg was damaged, he had to lean on my injured right collarbone which was extremely painful. When I thought I could not continue we fell off the edge of the sandbank into deeper water and so had to return to the aircraft.

We discovered that the aircraft's force of impact on water and/or sandbank had caused both engines to be thrown forward twenty to thirty feet (about ten metres). We sat on the edge of the port wing watching the oxygen bottles and other objects exploding, one of which exploded with enough force to send the two of us from the wing into the water. The pilot then returned to the aircraft and emerged with the survival kits. There was one for each crew member, containing necessities to sustain us for one or two days. This included a small bottle of rum, which was most acceptable.

About 5.00 am an inflatable boat containing two occupants with Schmeiser submachine guns came to pick us up. When we were about half way to shore one of the petrol tanks on our aircraft exploded which looked very dramatic, particularly as we realised that if the Germans had been half an hour later we would still have been on the aircraft.

We were taken into the Sylt Luftwaffe headquarters and locked in a room. Our clothes were taken for drying and we were given hot soup. During the morning there was a loud explosion and some time later a lot of yelling. I later discovered that five German technicians went to examine our aircraft which was unfamiliar to them and while they were aboard the mine exploded killing all of them.

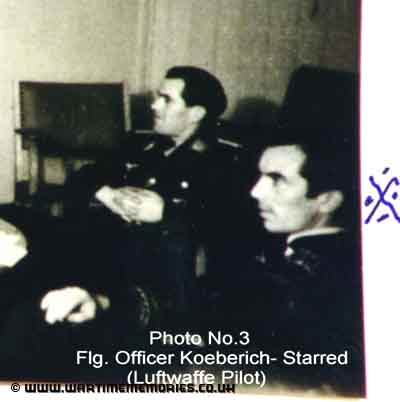

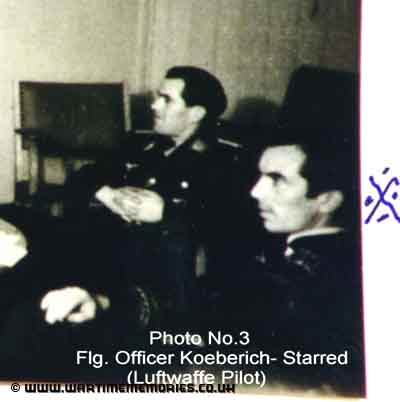

The pilot of the night fighter, Flying Officer Koeberich, came to see us during the morning and told me he had broken off his attack due to a fire in one engine and was preparing to land his aircraft when I saw him. He also advised that his gunner, Corporal Schubert, died that morning of gunshot wounds. From a report given by his replacement gunner, he was a successful pilot. When Reichsmarshall Herman Göring heard the details of the loss of the ME110 night fighter and the death of the gunner, he took the view that the Sylt Commandant had been negligent in sending assistance to his downed air crew and therefore the delay caused the gunner's death. This officer was relieved of his command at Sylt but I do not know the final result of his punishment.

Flying Officer Koeberich talked for some time in a friendly manner and described his training. He was recruited before the war and had had at least three years night fighter experience. At the end of our conversation he insisted that I receive some bandages. This was followed to the letter and I was presented with a two inch wide bandage to set a broken collarbone! Flying Officer Koeberich was later killed in a Royal Air Force air raid at Quakenbruch on Easter Sunday in 1944, when a bomb struck the air raid shelter he was in and the roof collapsed on him.

Our two injured crew members were taken to hospital but when I asked for some treatment I was ignored and this was repeated at each of the camps in which I was later interned. I cannot explain the reason for this but I was told on capture that as an Australian I had no right to be involved in this war. My injuries were not severe but treatment would have been beneficial. I had a broken collarbone, a broken nose, small fragments of shrapnel in my right thigh, Perspex splinters in my face, burns to face and hands and some damage to my knees. The two injured crew members were repatriated during 1943 in a prisoner exchange.

The pilot and I were transferred to Frankfurt for intensive interrogation and while there a bomb was dropped on the camp which destroyed some of the perimeter fencing, which caused a fair amount of excitement amongst the Germans. During the period of three days, I was locked in a room containing a bed, a table and a chair and waited for the interrogator. I was lucky enough to find a piece of a needle and a small piece of mirror. With these implements I passed the time digging out the Perspex splinters from my face.

We were then sent to Stalag Luft 3 passing through Hamburg. While on the platform, waiting for the train, we were joined by other prisoners and when the train pulled into the platform and we started to embark, the crowd on the platform which was now fairly large, started to push forward towards us which looked fairly dangerous. Our two guards pushed us into the carriage, jumped in and slammed the door behind them. They then made a great show of the fact that they were armed. Fortunately, the train left without delay.

Some distance from the station we saw evidence of airmen having been murdered. We arrived in Sagen and except for some prisoners from other camps who were to act as cooks we were the first batch in this camp. We spent about a year in this camp and were then transferred to Heyderkrug Stalag Luft 6 near the Baltic coast. After being sent to several other camps we finished up at Fallingsbostel and later were sent on a forced march, ostensibly to Lubeck. This was terminated after some weeks when we made contact with the British flying column who brought in some arms. I eventually returned to England on 7 May, 1945 in time to celebrate the end of the war.

As previously mentioned we were the first prisoners to go to Stalag Luft III but soon prisoners from other camps started to arrive and with the increased number of aircrew being shot down due to the escalating number of aircraft being used in each raid, it was not long before the camp was officially full.

At this time the camp consisted of only one compound in which prisoners were housed and a large compound for the administration block. The camp had been carved out of a pine plantation and the vorlager was still littered with stumps where the trees had been felled. Other huts were built until the maximum was reached. This left only enough room for a parade ground where the twice daily counts were conducted.

The huts were designed to hold about 100 prisoners in each and were divided into two rooms. The only furniture consisted of two-tier beds originally fitted with full sets of bed boards on which were placed mattresses filled with straw, often wet. By direct order from the Chief of the Luftwaffe, Reichsmarshal Hermann Göring, we were not permitted to leave the camp for any purpose including working on farms. The concentration, therefore, became fixed on the food we would eat when we got back home and the method we could use to accomplish this. Many harebrained schemes were put forward in all sincerity but in most cases the proponents were persuaded not to try.

One aspect of this, however, probably had some good effect. Realising that any successful escape must involve a great deal of walking, many of us decided to exercise as much as possible and as the only method available to us was walking, we took this up. Due to the large number of men wishing to walk on the one available track which was around the perimeter fence, keeping clear of the warning rail, it was agreed that we would walk using only left-hand circuits (all turns are to the left). I should mention that to cross the warning rail was tantamount to suicide as the guards had instructions to shoot for any infraction of this regulation. We had a good respect for their ability to hit their target with either a rifle or machine gun so we did not take any chances. They had to attend weekly shooting practice on the practice range which was placed within easy earshot of our compound probably as a warning. Our ambition was to walk 30 kilometres which was considered the distance we would have to travel at least in the first day and probably on some subsequent days if we succeeded in escaping. This remained an ambition for most of our time but as the effects of restricted diet took effect it seemed more like a pipe-dream.

We were provided with personal washing facilities which consisted of a double-sided trough with a pipe in the middle holding a number of taps. It will be appreciated that a lot of water was spilt on the floor through this method and in the winter months the water froze making a hump of up to thirty centimetres in height, which made it quite difficult to use.

After some months in this camp we were attacked by hordes of fleas and it became a daily ritual to search the blankets and exterminate the pests. After some time of enduring this, we were shepherded to a formerly forbidden area of the camp and into a delousing facility. In this building were clothes racks on wheels and we quickly stripped off and placed our clothes on them. They were then wheeled into what I can only describe as an oven. We were permitted to enjoy the luxury of a hot shower - the first in a long time. We all agreed that this was the most enjoyable way of combating the attentions of fleas. Having been established, this procedure was repeated at irregular intervals.

We had little to do so boredom became a serious problem. On one occasion we were offered the chance to help remove the stumps of the pine trees displaced by the building of the camp which was, of course, due for extension. The Germans had dug out most of the sand from the stumps and our task was to lift the stumps out of the ground and onto a cart. We worked in teams of six and were provided with a tool referred to, almost reverently, as die maschine. I think it was designed by da Vinci and consisted of a pine log tripod with two lever, or handles, attached to it. A sling was attached to the stump and connected to hooks on the handles. With three of us on each handle the work was not very strenuous. We were paid for this engineering feat in what was known as lager geld, which was acceptable only in the canteen for the German troops and then only for specified articles.

One task we were to perform was to peel the vegetables for the daily soup. These were almost invariably potatoes which had spent the winter stored in the underground clamps. A great deal of the potatoes was wasted because of this which allowed the potatoes to rot. The main addition to this was mangelwurzels which are an oversize swede-turnip grown for cattle food.

Most of the ground around the huts was taken up by very small garden plots in which the owners spent a disproportionate amount of time but they still made a valuable contribution, firstly, in providing some interest and secondly, as a cover for the tunnels attempted. One of these was a garden about one and a half metres square, covered by a wooden board on which the plants were growing. The whole garden was lifted up, the operator slipped underneath and the garden replaced. Unfortunately, this was not a successful attempt. A number of such schemes were attempted but none reached more than halfway between the warning rail and the perimeter fence. If my memory is to be relied upon, this would equate to about seven metres of tunnel which, considering the difficulties faced, was quite a creditable effort. The worst feature of all this tunnelling was the fact that because the soil was impoverished sand it was vital to shore up the tunnel even over relatively short distances and the only suitable material was our bed boards. It was decided that a total of five boards would support a man's weight and from then on our beds were slightly less comfortable and this situation continued in each camp.

It may be of interest that this was the camp from which a mass escape was made and on which the American film "The Great Escape" was loosely based. A few weeks before this escape was made we were transferred to Stalag Luft VI at Heydekrug which was situated not a great distance from Königsberg which gave us all the hope that it might be possible to board one of the ferries to get to Sweden.

After a short period of settling in we were paraded and an announcement made by the Camp Commandant that the escape from Sagen had been made and that in recapturing them, some of the prisoners had been shot. This, of course, caused a strong reaction for which the guards were prepared. They had been reinforced and our demonstration was quickly stifled by some manhandling.

This camp, probably because of the more severe weather conditions, had brick buildings and even a shower block. Each building held about 50 prisoners in one room. A heating stove was provided but no fuel.

Each morning we gathered at the main gate to see the new prisoners coming in. One day I saw in the group a friend whom I made at OTU (Operational Training Unit). The new prisoner was Vic Oliver, who was an instructor when I met him, resting after completing a tour of operations in which he earned a DFM. He was a talented pianist and a keen music lover and we stayed together until the war ended and he shared my unorthodox return to Britain, which is described later.

While at Sagen I saw my first game of rugby and was later pushed into playing. I did not know the rules or objectives but received a short verbal instruction session. I do not remember the name of the position I was allotted but I do remember I was in the 'scrum', which I found very uncomfortable. Towards the end of the game all action stopped and we found that one of the players had broken his leg and was being carried off the field. This ended the game and my participation in rugby for the future. To be injured in this place was a disaster as even small wounds took a long time to heal.

One story is that of a young Polish pilot who had joined the RAF in a Polish squadron after the German occupation. He was subjected to a considerable amount of enticement and threats to encourage him to join the Luftwaffe. His parents were reputed to live about twelve miles from the camp. He was promised almost unlimited visiting privileges but did not waver in his refusal which, considering the state of hostilities was a very courageous stance.

One of the saddest stories is that of an 18 years old gunner. He had joined the regular RAF and on 3rd September, 1939 was sent on a raid on a city in France. He was shot down and spent a considerable time as a prisoner. The trauma proved too much for him and his mental control was affected. We tried to have him included in the prisoner exchange which was carried out in 1943. I am not sure whether he was included but I believe he was as I did not see him after that time.

At each of the camps in which I was held someone had managed to create a radio on which we were able to receive the BBC news. In addition, we were told the German version of the progress of the war and we were, therefore, able to put together what we thought was a reasonable assessment.

At Heydekrug we were permitted to transform one of the wooden buildings into a theatre. We all laboured hard to do this. By working on this project we were able to steal some of the wood off-cuts which we used in our "blowers" to heat water to make tea. The apparatus was really a small forge made from food tins and with a belt-driven fan they were very efficient and boiled a 'billy' with very little fuel.

The theatre, however, was intended, in part, to deflect unwanted attention from the search for the radio. Because the local Gestapo had taken over camp searches, the possession of a radio could have had dire consequences so it was decided to burn down the theatre. This occurred late at night and although the German guards tried to extinguish the fire they could not and we were called upon to join the bucket chain. The search for the radio became less intense although regular searches of barracks and personnel continued.

There was a game which was played, as in other camps, where inmates, after being counted, would move to another group to be counted a second time. One night the parade went for an extra two hours much to the chagrin of our guards. When the count exceeded the full complement of the camp we considered we were victorious. This game rebounded on us the next day when the local Gestapo took over the count. During this period the barracks were minutely searched and we spent about eight hours standing in snow waiting to be dismissed.

In order to fill in the waiting time, I engaged in conversation with one of the guards to discover his version of the state of the war. This was a complete failure but produced some humour. He was upset about the poor performance of their Italian allies and suggested that if our side would accept them as allies the Germans could win the war.

On a later search we were taken to a Gestapo colonel for interrogation and personal search and to show his authority he broke my last two cigarettes and threw them out on the pretext that I might have had a compass hidden in them. This wanton provocation made me lose my temper and I protested rather loudly for which I was hit from behind and commenced serving seven days solitary confinement in the camp "cooler".

One morning one of the guards in a postern tower heard that his family had been killed in an air raid the previous night and he opened fire with his machine gun. A number of near misses occurred but I did not hear of any casualties.

The impossible escape ideas still came up. While walking just before dusk I saw two of our number lying in a shallow creek which ran through one end of the compound. They had the intention of digging under the fence after dark, fortunately, they were persuaded to give up the attempt.

One of the English prisoners had apparently spent a considerable amount of time in pre-war Germany and could speak the language well enough to pass as one of them. I do not recall his name but he seemed to be able to go out and in at will. On one occasion he agreed to escape and gather information to help an escape bid and then return. He later vanished from the camp and enquiries elicited the statement that he had been sent to a holiday camp - a statement that left us full of foreboding.

After about twelve months at this camp we were transferred to another in Thorn in Poland. Transport was in the usual horse boxes which were always labelled '40 hommes-10 horses'. These railway vehicles were divided into three sections, the end ones for the horses and the middle for their attendants, in our case, for the guards. The wagons were built with rather heavy planks with a gap of about 75mms between them. The wagons were not sufficiently wide to allow us to lie down straight and so were rather uncomfortable.

When entering Thorn railway yards I was dismayed to see groups of women under guard and re-ballasting the tracks. This involved using picks and shovels. By the way they swung the picks they must have been in great fear.

On arrival at the camp we were ushered into a reception area which was filled with three-tier beds and wet straw mattresses. We were, however, only kept in that place for a few days and were then transferred to our new homes. We discovered that a large number of Australians (AIF members) were being held here and I even met one who was a friend of my future wife. My stay in that camp convinced me we were bringing a lot of trouble on ourselves by our actions.

We had been told in England that if we became prisoners we were to attempt to escape if possible and to cause enough trouble to ensure that as many of the German forces as possible were required as guards and I believe we all followed this course fairly successfully.

The practice of locating Prisoner of War camps next to service establishments was followed and at Sagen we must have been next to a Luftwaffe camp charged with testing new models of aircraft. One ME110 used to make an extremely low-level pass over our camp each morning until an idiot threw stones and eventually hit the aircraft. This could have resulted in a large number of casualties as most of us were out waving encouragement to the pilot. We were later privileged to see testing of other models, such as, the new two-engined super dive bomber.

At another camp (probably Fallingbostel) we were next to a rocket testing site. These were not the big ones like the V1 and V2 rockets but rather limited to about 1.0 to 1.5 metres in length. There seemed to be a problem with steering as large numbers careered wildly on the way up and crashed back to earth - fortunately not in our camp.

Events of great interest were the sight of Mosquito aircraft being pursued by German fighters and relying purely on their superior speed to escape. A similar occurrence was sighted when our first jets showed a clean pair of heels to the FW190's (Focke-Wulff 190's), which were probably the best of the German fighters.

Some time later we were transferred again, this time to Fallingbostel. The camp was not very different to others and had brick buildings. The interesting item was the small road roller used to collapse tunnels. However, the distance was too great from buildings to the fence and to my knowledge only one succeeded in reaching this distance and was collapsed. Another radio operated in this camp and our spirits soared and sank as the fortunes of war changed.

One aspect of prison life which was not too pleasant was the use of guard dogs to enforce orders. This was more prevalent after the daylight raids on Germany commenced. We were supposed to proceed to our barracks and not make any gestures which could be interpreted as signals to the aircraft. After shouted orders followed by threats with rifles, the dogs would be let loose which had an immediate effect with prisoners running madly for shelter.

The trip to Fallingbostel turned out to be an interesting interlude. We were crowded into the usual horse wagons and at one station, which had a large marshalling yard, we stopped and the guards left the train. Naturally we tried to assess the chances of getting away but as some of our members tried to open the wire doors we discovered that each wagon was guarded by a young soldier equipped with a sub-machine gun. An ambulance train carrying many Red Crosses passed us heading in the opposite direction and the inmates appeared to be very fit to our eyes.

Shortly after this we were attacked by three American Lockheed 'Lightning' aircraft. I was climbing the wall for a better view when firing started and dived for the floor. A number of nasty holes appeared in the walls but we decided we were probably not the prime target as on the second set of rails from us stood a train of fuel tankers some of which were burning.

Later that day as the temperature started to drop we stopped to cross another train heading in the opposite direction to us. As this train neared we heard the most unearthly sound, which was spine tingling. The train consisted of steel wagons covered in pig netting and the noise was made by Frenchmen being transported as slave labourers to Germany and were crying for help to relieve their sufferings. We could do nothing for them but their cries gave me nightmares for some years after the war. I cannot imagine how many were in the wagons and how many could have survived the night.

From the camp at Fallingbostel we were able to hear the sound of the canon at the time the crossing of the Rhine was being pursued. This continued day and night for some days and when we found out the attempt had been successful we were elated.

About this time the Germans apparently decided we were of some value to them and arranged an evacuation. We were to travel by train to Lubeck but when we arrived in Hamburg a large air raid was in progress which did considerable damage to buildings and railways. As our train could not proceed we were required to finish the journey on foot. Our route is now a mystery to me but I do remember passing through Schleswig-Holstein and days later crossing the river Elbe by ferry which looked like a small landing barge. During this embarkation of about 100 prisoners, two British aircraft appeared. They came down low but did not fire, much to our relief. We then walked about 30 kms per day sleeping in barns on farms each night. We did, however, have a rest day on Sundays. Our biggest fear was that of being 'strafed' by British aircraft and indeed this happened to the group which left after ours. We did, however, become adept at diving into the ditches on each side of the road.

Early in the march most of us suffered from an internal complaint which struck suddenly and left no time to seek a suitable location. The first two casualties occurred one morning and they dropped behind. Two guards stayed with them but I do not remember them ever rejoining the party.

My own case was more amusing. We had stopped in a barnyard and dug a hole. There was no cover so the hole was in plain view from the road. While I was using this convenience two girls drove up in a wagon of potatoes and waved quite vigorously. They were not in a hurry and were quite happy to stay and talk to the group.

Later in the march some of the guards left us, apparently deserting military service. The sergeant in-charge managed to obtain bread at each town except for one which gave him flour, which we could not cook and so we went hungry.

One night, while being overcome with an attack of our illness, I shot out of the tent we were using, dived underneath the bayonet of the guard and went to the hole. He followed me and when he saw what was happening he left me alone. I did not return but decided to try to escape which, considering our condition and location, was a very stupid choice. When daylight returned I found myself in another farmyard which sported an extremely large clump of what looked like rhubarb. I decided to hide in them until I planned my next move.

There was a fairly large building about 250-300 metres away with two farm wagons outside - these were drawn by the usual one horse and one cow. Soon a number of men started loading the wagons with objects brought from the building. From my position, and considering the manner in which the objects were thrown onto the wagons, I decided they were human bodies. I have not been able to confirm this conclusion but it gave me a great deal of concern at the time. I then decided to rejoin our party if I could find a way to do so without being shot. Fortunately I was successful, thanks to the cooperation of the members of our group.

My memory says we continued to walk east for some time, probably two to three weeks, when a guard to whom I was talking made the comment "Tomorrow, we will be the prisoners and you the guards". Despite my probing he would say no more. By some means which I cannot describe, we found out that a flying column was approaching and that the army would not be too far behind.

Early the next morning we took off through the 'bush' and made contact with a jeep containing a British Lieutenant and a corporal who advised us to return to camp and that they would come the next morning and bring some arms. They kept their promise and appeared with six rifles. This was sufficient as our guards were ready to surrender and no other military personnel were too close. All this occurred on 2nd May, 1945. We were not far from town and a group of five of us joined forces and walked. The name of the town eludes me.

When we arrived in town we looked for accommodation and transport but we found only the former. A large building of apartments seemed to contain only women and when we explained our situation as being escaped prisoners of war, a number of the women appeared afraid of us, which was, of course, understandable. After some talk they seemed to accept our assurance that we meant them no harm. One of them, after discussion with her neighbours moved her things to the next apartment and lent us hers for the night. These women told us they were the widows of German soldiers killed in Stalingrad. I do not know if this was correct and some other explanations for a large number of women in a building circulated.

However, they adapted to the situation and in the apartment we were actually cooked bacon and eggs. In return I gave the woman some tins of German rations that I had acquired. As we drifted into town we found that some British soldiers had set up a sort of canteen and served hot tea and white bread and butter. When I saw the white bread I thought it was sponge cake and ate half of it before I realised I could have put butter on it.

Next morning we again looked for transport and despite several attempts could not find a vehicle good enough. Then I discovered an American major who seemed to be organising traffic movements and, at my request, told me to take a German motor truck parked on the road. It was, to my eyes, a massive vehicle needing five steps to the cab and room to sit five across. The largest vehicle I had ever driven was a three-ton Bedford. When I started driving out of town I discovered a lot of other ex-prisoners looking for a way out and before long the truck was full. I did not count the number of passengers but it seemed to be a full load. At this time we discovered we had been given a ration truck which was full of edibles. Our passengers were good providers and were divided into groups to look for liquor and fuel and they were quite successful.

The road was crowded with traffic but we were impeded only at a few spots. At one of these an ambulance pulled alongside us and in starting collided with us and tore out the side of the ambulance. When the American officer, who was trying to keep traffic flowing, investigated the damage, he found that the only occupants were two high-ranking Germans trying to get away.

We eventually arrived back at the Elbe River and had to say goodbye to our truck because the original bridges had been destroyed and were temporarily replaced by Bailey Bridges, which would not carry the load. We caught a ride on a jeep and it is still a mystery how the driver could have seen his way. We had men on the bonnet and others everywhere they could find a hand-hold.

Across the river we found a reception area where we stayed the night and embarked on a British truck for the next stage westward. At the end of the journey we saw our accommodation - there were hundreds of little tents in a paddock. Our group now consisted of only Vic Oliver and myself and we decided that as we required medical attention for some obscure stomach affliction, we would take off on our own. This we did and rode on all sorts of military vehicles including tank carriers and ate at any army establishment we could find.

The British soldiers were very hospitable and we were provided with food and beds. Although our clothes were disreputable we had no trouble in getting the army drivers to pick us up.

We eventually arrived in Brussels in the late afternoon and were too late to get clothing or money which I desperately needed to go into town. We then noticed a Douglas DC3 aircraft with its engines running and ready for take-off. We both ran as fast as possible and were lucky enough to reach it in time. We thus became the first of our group to reach England.

We arrived at Bishop Stortford (now renamed) and travelled to a RAF hanger where a reception was laid on and we were ushered from the bus to a de-lousing centre where we were pumped full of DDT. From this area we were met by a WAAF (Women's Auxiliary Air Force), dressed in her best, and ushered to a table. I found this a little daunting as I must have smelt of DDT and had on a pair of trousers which had a large tear in the bottom. This was, of course, the first female I had met for three years.

We were later taken to our accommodation for the night and travelled to Brighton the next day arriving in time to be issued with some clothing but too late for money. This was, of course, VE Day and big celebrations were expected.

As I left to go into town I met a New Zealand soldier who lent me £5, which we proceeded to spend. By this time we had been joined by some WRNS (Women's Royal Naval Service) and one or two other servicemen. We danced in the streets and drank large quantities of beer and were all very happy. The next day when entering my hotel I was confronted by my cousin whom I had not seen for some years.

We were placed on a diet guaranteed to add body weight which included a gallon (4.5 litres) of milk per day. After being on this diet for ten days I was weighed for the issue of an identity card and was amazed to find I was then 35 kilos - my normal weight was 60+kilos.

Towards the end of August 1945 we embarked on the ship 'Orion' for our return home. This ship had been completely converted to a troop ship and, therefore, provided no storage for gear and had hammocks to sleep on. This was my first experience with hammocks and I was not impressed. We travelled by way of the Panama Canal. When in mid-Pacific, the Captain announced that he had heard that the Japanese had surrendered but as he had no official orders the ship would carry on under wartime rules, which included anti-aircraft practice with rockets.

We landed in Sydney and an English officer who had been designated 'Officer Commanding Troops' issued an order that we would not be granted leave and must remain on the ship. It was later discovered that there was to be a reception at the local RAAF station, which we attended. The next day he tried to enforce his order but was unsuccessful and I met my brother for the first time in five years.

The voyage to Fremantle was quite rough but was worth the worry when we arrived to see waiting on the wharf, the welcoming party consisting of my father, mother and my future wife, Phyllis, who was still waiting for me after my absence of five years. We married in 1946, had a daughter and a son, and 56 happy years together.

My crew were:

- F/S S.Willett DFM. pilot

- F/S S.E.Packard

- P/O N.Hannah

- F/S H.S.McDonald

- Flying Officer L.T. Manser, VC.

- Sgt D.A.Williams RAAF

- Sgt C.J.Scott (d. 30 April 1942)

- Sgt C. Alf Miners. RAAF

|

Sergeant Robert Noel Harper flt eng 50 Squadron (d.8th Jul 1944) Robert Noel Harper was the Flight Engineer of Lancaster VN-J of 50 Sqd.

This young man, aged most likely 19 years old, was killed when their Lancaster crashed on the night of July 7, 1944 with 5 of the crew. The pilot, Alan Laidlaw from Winnipeg, Manitoba was ejected from their Lancaster plane. Robert Harper is burried in France, a small village called Meslin Mauger, near Roen. Their plane was one of 31 planes shot down by the German on that night. 208 Lancasters were sent, 13 mosquitos were sent to bomb at St. Lue d'Esserent the V-1 flying bomb storage depot. This fourth attack was part of the Operation Crossbow. It was a great victory. Does anyone know anything about this young man?

The crew were:

|

Sergeant Derrick Austin w/op 50 Squadron (d.8th Jul, 1944) This young man, aged most likely 20 years old, crashed on the night of August 7, 1944 with 5 of the crew. The pilot, Alan Laidlaw from Winnipeg, Manitoba was ejected from their Lancaster plane. Derrick Austin is buried in France, a small village called Meslin Mauger, near Roen. Their plane was one of 31 planes shot down by the German on that night. 208 Lancaster were sent, 13 mosquitoes were sent to bomb at St. Lue d'Esserent the V-1 flying bomb storage depot. This fourth attack was part of the Operation Crossbow. It was a great victor.

Danielle Lawrence for Alain Laidlaw now 86years old.

|

F/Sgt John Manning 61 Squadron My father, John Manning, served as a Flight Sergeant/Air Gunner on 61 Squadron, flying Lancasters based at Skellingthorpe, an airfield shared with 50 Squadron at that time.

Dad had a roll-out picture taken (he thinks) at the end of the war with aircrew of both squadrons sitting on the wings of a Lancaster. This photo was unfortunately lost when my sister died, as she had been looking after it.

Dad is, thank God, still with us and still very sharp, but he misses his photograph. Has anyone out there got a copy they can scan?

|

Flt.Lt Hubert Arthur Spencer 61 Squadron I qualified as a wireless operator for aircrew and joined 61 Sqdn in February 1945 and operated from Skellingthorpe until May 1945.

|

Flt.Lt Ron Aston 61 Squadron LANDING ON THREE! Ron Aston (a survivor) now living in Gordons Bay South Africa.

November 25th 1944 was a wet wintry day in Wigsley, Nottinghamshire. Cloud was low and it was dull grey with showers. I was there to convert from twin engined Wellingtons to Stirling four engined aircraft, prior to going on to Lancasters and thence to joining a squadron.

Today my crew and I were to undertake our first cross-country exercise. Well prepared, with four hours solo, briefed, in possession of the met forecast, we took off after lunch into the murky day. The weather didn't present any problems, we were well trained on instruments both in cloud and at night, and we knew we would have to make a night landing on our return. I had a good Navigator and was confident that this would be just another exercise... How wrong could I be?

We were climbing on course and levelled out at about 6000' in and out of cloud. I was busy sighting the two port engines to synchronise the propellers, after which I would do the same with the starboard ones. This is done by simply adjusting each pair of throttles so that the pair each side are running at exactly the same speed - this cuts out the droning associated with multi-engined piston aircraft. Whilst adjusting the throttles, the port outer throttle lever gave me a severe rap across the knuckles which, despite the gloves, hurt. I immediately asked the Fight Engineer to check the instruments for that engine. I knew that there must have been a backfire through the fuel induction system which could be caused by a broken valve or faulty ignition. Either way is wasn't good news, especially when the Engineer reported that the engine was running hot and losing oil pressure rapidly. There was no choice but to tell him to feather the prop and shut down number one engine.

Now I knew that the Stirling was underpowered, indeed, it was a very heavy and ponderous aircraft to fly. But I had no idea how it would perform on three engines... Shortly I would find out! With the remaining three engines now at full power, I now had a course to steer for a return to base, but there I was with both feet on the same rudder pedal, both hands straining the ailerons to keep the port wing up, and losing height.

Returning for an emergency landing, at about 3000' feet I was holding height. We were now in cloud and it was getting dark. I called the Wigsley tower for an emergency landing and was told to stand by. This I accepted as I knew they would want to get the emergency vehicles at the ready. Meantime the Engineer and I were recalling items from the Pilot's Notes for the Stirling. One point kept coming back - on three engines with wheels and flaps down you cannot overshoot. This meant that once these were down we were committed to land. Then another thought occurred to me; I had never been demonstrated a three engine landing or practised one with an instructor! So I assumed it was the same as a single engine landing on a twin, so it didn't worry me too much.

Continuing to call base for permission to break cloud and land, each time they came back with the same message to stand by. After half an hour of flying the crippled aircraft around in thick cloud I was beginning to sweat blood. Calling base again I told them I was breaking cloud and preparing to land at the first aerodrome I saw. Immediately they came back with the instruction to divert to Waddington. My Navigator gave me a course to steer and an ETA of eight minutes. At 1000' we broke cloud into a clear black night. In a short while I saw the runway lights and the Drem system of an airfield dead ahead and told the Navigator that I could see Waddington.

Calling on the emergency frequency I requested permission to join the circuit for an emergency landing. This given, I reported in the circuit and again on downwind. As I turned onto base I lowered the undercarriage and still with plenty of height, lined up with the runway as I turned onto final. As we reduced speed it became more difficult to keep straight. At 300' I called for full flap as I was then certain of making the runway. Just as the flaps came down I was given a red from the runway caravan and a red Very light, just in time to see another four engined aircraft taxi out onto the runway for take off...

The very same runway we were now committed to! I had no time to be horrified, I knew that an overshoot was impossible, and the instinct for self preservation took over. There was no time to think; I knew I had to land and I didn't fancy landing on top of the other aircraft. So I did the only thing possible - turned 10„a to port and proceeded to land on the grass, looking out of the starboard window to judge my height from the flare path, seeing also the other aircraft take off. Fortunately there were no obstructions and we made a fair landing.

Making back for the runway I turned off left, parked and shut down, with an incredible feeling of relief! Most of the crew had no idea what was going on - just that I had landed on the grass - but those up front soon put them wise. A van arrived shortly and we all piled in. I asked to be taken to the tower and arriving there marched up the steps feeling very much put out and more than a little peeved. I opened the door with a bang and asked who the hell let the aircraft take off whilst I was coming down on an emergency landing. They all looked puzzled and said they had no knowledge that I was making an emergency landing. I was quick to remind them that I had been talking to them only minutes before on joining the circuit... this they denied all knowledge of... and then it struck me... I asked "this is Waddington isn't it?" "Oh no!" they said, "this is Swinderby!" I had landed at the wrong airfield!

24th February 1945 was my first daylight raid, the target being the Dortmund–Ems Canal Canal, Germany. I paid particular attention to the briefing to be ‘on the ball’ and to make sure of my designated position in the ‘goggle’. Unlike the US Army Air Corps, the Lancaster wasn’t designed to fly in formation; we kept position in loose groups of aircraft.

We took off with a full bomb load from our Linconshire base early afternoon, expecting a return night landing. As we went out to the dispersals I kept an eye on the other aircraft that I was to fly alongside, so I could take off as close to them as possible. There was little wind and we used the whole runway to take off. Alas, once airborne it was impossible to catch up with those in front. We were climbing at nearly full power so I did what everyone else did and slipped into the gaggle at the nearest point and held station, which wasn’t easy as the Lancs in front & on either side began to wander. daylight raids demanded more attention than keeping course at night. All went well for a couple of hours, but then the Wireless Operator announced that the op had been abandoned due to heavy cloud over the target, and that we were to return to base. I thought that we should go for an alternative target, but no, we were to return to Skellingthorpe. As we turned I could see some of the other Lancs dropping their bombs into the North Sea. As we flew back 4Flight Enenginee and myself had a discussion about the weight of the aircraft for landing. The bomb load comprised fourteen 1000 lb bombs with half-hour delay acid fuses. We had consumed fuel on the engine run-ups prior to take off, climbing to height and cruising for two hours since then.

The flight engineer gave his computed figure which showed that we were well over the maximum permitted weight for landing. Should I jettison some or all of our bombs? Hell, to come all this way and drop those precious bombs into the ocean seemed such a waste; overweight or not, I would take those bombs back. I was confident that I could handle it, as the Lancaster was the most forgiving aircraft that I had flown, so we continued back in the dark. I could see other aircraft landing as we approached Skellingthorpe, and I could already imagine the taste of the hot cup of cocoa as we entered the crewroom. I called up on the radio and we joined the circuit. Suddenly the whole world lit up. A huge explosion had taken place on the airfield, and even at 1000 ft we felt the shock wave. Immediately I turned off the navigation lights as I thought German night fighters had come back with us in the bomber stream, as sometimes happened. After a few minutes I was diverted to Woddington, just a short hop away from our own base, and was soon on the approach to landing there. In the meantime, with all the excitement, I had other things on my mind and had forgotten about our weight. However, all this came rushing back to me as we were about to land, but thankfully all went well. However, I was surprised when the groundcrew directed us to the far side of the airfield, where we began a long wait in the dark.

Eventually, after we had tucked the aircraft down for the night, a ~n from Skellingthorpe picked us up. The driver told us that another LAnc with bombs on board had exploded, killing its crew as well as seven ground crew, and destroyed other planes and hangars.

It was a very sad journey home, and we got to bed in the early hours of the morning. Early that same morning I was woken with the news that I was to return to Waddington to collect our aircraft, as it was required for a sortie that same night. A little piece of RAP St Mowgan’s 42 Squadron History: Flown by squadron CO Wg Cdr Carson, on 2nd Auciust 1965, Mk III SF~ack WR958 dropped supplies at a rendezvous 400 miles out into the Atlantic.

Robert Manry, sailing a 14 ft dinghy from Falmouth, Connecticut USA to Falmouth, Cornwall was making the British National press headlines at the time and, of course, someone at Mob thought it great PR to drop mail and fresh fruit to sailor Manry. The skill in finding this tiny boat in the middle of the ocean didn’t occur to anyone, except the aircrew who had to find it - pre-GPSI. The Press were in the accompanying shack to witness and photograph the event, and this is the photo syndicated at the time.

I can only tell you how relieved the navigator in ‘b’ was when the aircraft landed - the crew also had an AVM on board, a future AOC for 18 Group! Waddington knew of the tragic accident at Skellingthorpe before we landed, and didn’t want a repeat performance with another of our aircraft. Last night there had been seven aircraft lined up with ours, but this morning mine was the only plane there and all the other crews were back in bed - where I wanted to be as I expected to fly an op again that night. Meanwhile, there was not a soul in sight by our aircraft - everyone knew that my bomb-bay was full of bombs! On entering the aircraft we were staggered to see the fuselage aft of the tail door stocked with the fins from our 1000 lb bombs, each standing chest-high. There were also ammunition boxes containing the bomb fuses. With so much weight in the rear of the aircraft it was impossible to take off, so something had to be off-loaded. I then contacted control and asked if the armourers could take off some of the bombs. But we waited and waited, and nobody came. After two hours I had had enough, so I sent the bomb aimer to see if the bombs were safe. He did just that and reported that all was well. I started the engines, did the proof light checks, switched off the radio, and then told the bomb aimer to release the entire bomb load on the grass. We felt a jolt as the bombs left the aircraft, and I could feel the Lanc breathing a sigh of relief, just like me. To clear the tail wheel around the bombs I locked one main wheel and pivoted the Lanc around. Fortunately this manoeuvre worked, and as I headed for the runway I glimpsed our 14 large bombs laid out neatly on the grass. I then took off and landed at Skellingthorpe a few minutes later. Believe it or not, I never heard another word about the incident. Thankfully I also didn’t have to fly that night, but I did return to Dortman Elms Canal several times.

Ron is alive but not too well, in Gordons Bay South Africa.

|

Flt.Lt Ron Aston 61 Squadron Skellingthorp

By Ron Aston

Old War Stories: l3Bombs AwayITM

Shack Drops a Welcome

Ron Aston,.

Serving in the Royal Air Force during WW2 as a F14’ht Lieutenant Pilot flying 61 Squadron’s Lancasters~ from RAF Skellingthorpe, Lincolnshire. Ron hasn’t been too well recently. 30/05/2010

24th February 1945 was my first daylight raid, the target being the Dortmund–Ems Canal Canal, Germany. I paid particular attention to the briefing to be ‘on the ball’ and to make sure of my designated position in the ‘goggle’. Unlike the US Army Air Corps, the Lancaster wasn’t

designed to fly in formation; we kept position in loose groups of aircraft.

We took off with a full bomb load from our Linconshire base early afternoon, expecting a return night landing. As we went out to the dispersals I kept an eye on the other aircraft that I was to fly

alongside, so I could take off as close to them as possible. There was little wind and we used the whole runway to take off. Alas, once

airborne it was impossible to catch up with those in front. We were climbing at nearly full power so I did what everyone else did and slipped into the gaggle at the nearest point and held station, which wasn’t easy as the Lancs in front & on either side began to wander. daylight raids demanded more attention than keeping course at night.

All went well for a couple of hours, but then the Wireless Operator

announced that the op had been abandoned due to heavy cloud over

the target, and that we were to return to base. I thought that we should go for an alternative target, but no, we were to return to Skellingthorpe. As we turned I could see some of the other Lancs dropping their bombs into the North Sea.

As we flew back 4Flight Enenginee and myself had a discussion about the weight of the aircraft for landing. The bomb load comprised fourteen 1000 lb bombs with half-hour delay acid fuses. We had consumed fuel on the engine run-ups prior to take off, climbing to height and cruising for two hours since then. The flight engineer gave his computed figure which showed that we were well over the maximum permitted weight for landing. Should I jettison some or all of our bombs? Hell, to come all this way and drop those precious bombs into the ocean seemed such a waste; overweight or not, I would take those bombs back. I was confident that I could handle it, as the Lancaster was the most forgiving aircraft that I had flown, so we continued back in the dark.

I could see other aircraft landing as we approached Skellingthorpe, and I could already imagine the taste of the hot cup of cocoa as we entered the crewroom. I called up on the radio and we joined the circuit. Suddenly the whole world lit up. A huge explosion had taken place on the airfield, and even at 1000 ft we felt the shock wave. Immediately I turned off the navigation lights as I thought German night fighters had come back with us in the bomber stream, as sometimes happened.

After a few minutes I was diverted to Woddington, just a short hop away from our own base, and was soon on the approach to landing there. In the meantime, with all the excitement, I had other things on my mind and had forgotten about our weight. However, all this came rushing back to me as we were about to land, but thankfully all went well. However, I was surprised when the groundcrew directed us to the far side of the airfield, where we began a long wait in the dark. Eventually, after we had tucked the aircraft down for the night, a ~n from Skellingthorpe picked us up. The driver told us that another LAnc with bombs on board had exploded, killing its crew as well as seven ground crew, and destroyed other planes and hangars. It was a very sad journey home, and we got to bed in the early hours of the morning. Early that same morning I was woken with the news that I was to return to Waddington to collect our aircraft, as it was required for a sortie that same night.

A little piece of RAP St Mowgan’s 42 Squadron History: Flown by squadron CO Wg Cdr Carson, on 2nd Auciust 1965, Mk III SF~ack WR958 dropped supplies at a rendezvous 400 miles out into the Atlantic.

Robert Manry, sailing a 14 ft dinghy from Falmouth, Connecticut USA to Falmouth, Cornwall was making the British National press headlines at the time and, of course, someone at Mob thought it great PR to drop mail and fresh fruit to sailor Manry. The skill in finding this tiny boat in the middle of the ocean didn’t occur to anyone, except the aircrew who had to find it - pre-GPSI. The Press were in the accompanying shack to witness and photograph the event, and this is the photo syndicated at the time. I can only tell you how relieved the navigator in ‘b’ was when the aircraft landed - the crew also had an AVM on board, a future AOC for 18 Group!

Waddington knew of the tragic accident at Skellingthorpe before we landed, and didn’t want a repeat performance with another of our aircraft. Last night there had been seven aircraft lined up with ours, but this morning mine was the only plane there and all the other crews were back in bed - where I wanted to be as I expected to fly an op again that night. Meanwhile, there was not a soul in sight by our aircraft - everyone knew that my bomb-bay was full of bombs!

On entering the aircraft we were staggered to see the fuselage aft of the tail door stocked with the fins from our 1000 lb bombs, each standing chest-high. There were also ammunition boxes containing the bomb fuses. With so much weight in the rear of the aircraft it was impossible to take off, so something had to be off-loaded. I then contacted control and asked if the armourers could take off some of the bombs. But we waited and waited, and nobody came. After two hours I had had enough, so I sent the bomb aimer to see if the bombs were safe. He did just that and reported that all was well.

I started the engines, did the proof light checks, switched off the radio, and then told the bomb aimer to release the entire bomb load on the grass. We felt a jolt as the bombs left the aircraft, and I could feel the Lanc breathing a sigh of relief, just like me. To clear the tail wheel around the bombs I locked one main wheel and pivoted the Lanc around. Fortunately this manoeuvre worked, and as I headed for the runway I glimpsed our 14 large bombs laid out neatly on the grass. I then took off and landed at Skellingthorpe a few minutes later.

Believe it or not, I never heard another word about the incident. Thankfully I also didn’t have to fly that night, but I did return to Dortman Elms Canal several times.

Ron is alive but not too well, in Gordons Bay South Africa.

|

Sgt. David McDougal Buchan 50 Squadron My Uncle, Sgt David McDougal Buchan, was a Navigator serving with 50 Squadron at Skellingthorpe.

David and his crew.

Scan of a letter received from Skellingthorpe

|

Jack Campbell 463 Squadron My Grandfather, Jack Campbell, is a Canadian Second World War veteran who served as a mid-upper gunner in 463 Squadron, RAAF, 61 Squadron RAF. At my grandfather's request, I have recently transcribed his memoirs where he details his wartime experience, and his time spent at Skellingthorpe, from 1942 to 1944.

The Airbourne Years

|

F/Sgt. David William McCray 50 Squadron. (d.17th Dec 1944) I have been researching F/Sgt McCray for my Australian relatives as they believe that his name may be spelt wrongly in the memorial books in Lincoln Cathedral which I will return to in a moment. My distant cousin, David McCray, was a member of 50 Sqd in 1944. He was Navigator on Lancaster LM676, VN-W. which took off from Skellingthorpe at 1615 hrs on the night of 17/18th December 1944.

The Crew was

- P/O R E Amey DFC (Pilot)

- Sgt F Livesey (Flight eng)

- F/Sgt D W McCray (Navigator)

- F/O D R Kennedy (Air Bomber)

- F/Sgt G W Lane DFM (Wireless opp air)

- Sgt M J Cook (Mid Upper Gunner)

- Sgt R Shackelton (Rear Gunner)

The RAAR records show that the Lancaster was detailed to bomb Munich. Nothing was heard from the aircraft after take off and it failed to return to base. It was later established that the aircraft crashed at 2200hrs on the 17th December 1944 at Freimann Barracks Munich. Five of the crew, including David, were killed in the crash and two P/O Amey and Sgt Livesey survived the crash and were POWs. The five who lost there lives are buried in the Durnbach War Cemetery 48 km south of Munich. P/O Amey was wounded and sadly died of his wounds in hospital on 31st December 1944.

Sgt Livesey stated in a report that the aircraft crashed near to the target and both he and P/O Amey were blown out by the explosion.

Now we come to the spelling bit. On a trip by John McCray (David's Brother) to the War Grave in Durnbach it was noted that David’s surname had been spelt wrongly as "Mcgray" this has now been rectified. John also attended the unveiling ceremony of the memorial in Skellingthorpe with his wife Eva and learned of the memorial books at Lincoln Cathedral but they were unable to go there to see. Now John is unable to travel and he has asked me to try to find out if David’s name has been spelt correctly in the memorial books. I would be very grateful if anyone could give me any info regarding F/Sgt David McCray or Sgt Livesey.

|

F/O. Victor McConnell 83 Squadron (d.11th Apr 1944) I would like to tell the story of the crew of Lancaster ND389, my connection is slim, although I have spent many years researching the crew but I would like to add this in remebrance of the crew.

- P/O V. McConnell

- Sgt T/Powell

- F/O A.J.S.Watts

- Sgt H.S.Vickers

- Sgt W.Surgey

- Sgt G.H.Bradshaw

- Sgt W.J.Throsby

The first mention of the crew I have found is 13 October 1943 where they were identified as having been at 1660 Conversion unit at RAF Swinderby. Here they were learning to fly four engined bombers, having first been together as a crew on two engined aircraft, most probably a Wellington but possibly a Whitley.

On the 13/10/43 they left Swinderby to join 61 Squadron who were based at RAF Skellingthorpe outside of Lincoln. This squadron was part of 5 Group. They flew their first Operation 03/11/43 to Dusseldorf. They remained with the squadron until 30/04/44 and flew Operations to Modan, flew on operations to Berlin 5 times, plus Frankfurt, Stettin and Brunswick - so they were very much a part of what came to be known as 'The Battle of Berlin'. If they had stayed with 61 Squadron and completed 30 Operations then they would have completed a 'tour', however during this period Bomber Command was experiencing very heavy losses and the chances of a crew completing their tour was very slim - and all crews were all volunteers.

At some point whilst they were with 61 Squadron they must have volunteered to join a Pathfinder Squadron, this would have meant even more operations before they were considered to have completed their tour and as such the chance of survival became even less. They would probably have been considered as an 'above average' crew in terms of competence.