Pte. Thomas Philip Fisher Bage

British Army 4th Btn. Black Watch

from:South Shields

Now we are into the year 2003 there aren't many people left who grew up just prior to the Second World War, and who went through that War, whom we can talk to face to face. At 84 years of age Tommy Bage still clearly remembers what it was like. What happened to him should be recorded, as it is not something we should forget. There is a lot of archive film footage that shows the battles and the destruction that took place but nothing can quite compare to the recollection of the memories of someone who actually went through it. Many young men and women went off to war, and many of them never returned. What some of these young people went through is almost beyond the imagination of most of us today.

This is the true account of the life of that ordinary 'Geordie' bloke, Tommy Bage, who survived the difficult years of childhood like so many others who lived in the poor, industrial areas of Tyneside, but who, in his teenage years, was drawn into a terrifying and destructive war. A war that quickly made the boys into battle-hardened men, and gave those that survived chilling memories that they would never forget.

Tommy was born on the 23 July 1919 and christened Thomas Philip Fisher Bage. His father was George Heslington Bage and his mother was Sarah (nee Clasper). Tommy was the first one of twin boys, his brother Christopher Johnson following behind him into the world. They had an older sister Margaret Smart Bage who was twelve years older than they were. George was in work and Sarah kept house and looked after her family as best she could in those difficult years. They survived through those difficult years when poverty often led to disease that could so easily strike and wipe out whole families. George Bage had been through the Great War with the Durham Light Infantry and had been wounded in action. He was a very quiet, reserved sort of man, and his hearing wasn't very good, perhaps damaged in the war. Little did George and Sarah know, at the birth of Thomas and Christopher, that their twin sons would have to endure the ordeal of a long and bitter war when in the prime of their lives. The lads grew up in the poor, rundown riverside area of South Shields. They attended St. Stephens Junior School and later went on to Baring Street Seniors.

Tommy liked his school and did well in the Higher Grade Exams at St. Stephens gaining a Merit. The staff had encouraged him to go to Westoe Secondary School but his parents didn't want to split the twins up and the opportunity for a better education was missed, something he was to regret for the rest of his life. During his spare time Tommy took part in his favourite sports of football and cricket, and he joined the local Harton Cricket Club, and this led to many enjoyable outings to places like Horden Colliery, Boldon and other Tyneside places. The Harton Colliery Club had a good ground and there was often tea and cakes supplied by members' families for everyone to enjoy. Cycling was another pastime that he enjoyed and Tommy would often cycle to Boldon Colliery to meet friends there. On leaving school Tommy got a job on a building site next to Harton General Hospital where he worked with his dad and brother Chris for two years. He considered this quite a reasonable job that gave him enough money for an occasional visit to a pub, or more often a visit to the local cinema. Unfortunately there was trouble on the building site and all employees were told by the Company to leave. The cinema was where he met his wife-to-be, Peggy Morrison, whom he met there with her sister Jean and their friend Nellie. He promised to meet them again at the cinema to see stars Nelson Eddy and Jeanette McDonald in the film 'Rose Marie.'

The year was 1939 and it looked like war was imminent. Most plans made at that time would be drastically changed in the months ahead. Tommy and Chris were of eligible age for call-up to the armed forces and were very apprehensive about the situation. War was declared and shortly afterwards the air-raid sirens sounded in South Shields for the first time, causing all the people to run for cover in the newly-built Anderson Shelters.

About January 10th, 1940 Tommy was called up into the army and told to report to the Training Camp at Auchengate, Troon, Ayrshire in Scotland. He took the train to Newcastle and then another to Troon were he spent about 12 weeks in training before joining the Highland Light Infantry. He was first of all sent to Ireland to a Transit Camp to join a battalion before being posted to join the British Expeditionary Force (B.E.F.) in Rouen, France. His brother Chris had been called up to the Army Medical Corps (R.A.M.C.) in December 1939.

Tommy joined the 4th Battalion of the Black Watch. Arrived at Dieppe, France for transport to Rouen Transit Camp about March to join forward units. He proceeded to the forward lines to join the 4th battalion, the Black Watch but it was impossible to reach them as the German offensive was in full swing. The best plan was to return to the coast as the allies were virtually unarmed against the German tanks and planes. Allied machine guns had been over-run. An English officer and several N.C.O.'s made the decision to make for the nearest coastal port. Many brave men died trying to stop the avalanche of German forces bearing down on the Allied lines. On one occasion during the retreat stuka dive-bombers attacked fleeing French civilian refugees on a crowded road causing many casualties. The soldiers’ rifles were useless against the planes and Tommy felt completely helpless in the situation. The soldiers were unable to give much assistance, but did what they could using the supplies they had with them. Tommy thought to himself, "This isn't war, it's cold-blooded murder." On their trek to the coast many French civilians supplied what food, wine and water they could spare as the retreating soldiers made a slow march back to the coast. Tired, footsore and very weary they arrived at Dunkirk. Unfortunately the German pincer movement was cutting off their escape route, so the officer decided to try for Cherbourg. The soldiers were very relieved to reach the port, but also saddened to know that the Germans would capture many of their comrades. All remaining vehicles had to be destroyed before the remnants of the army were able to board the ships and boats waiting for them in the harbour. It was with great relief that Tommy arrived back in Bournemouth and on English soil once again. They were sent to a casualty clearing station to rest and then moved first to Perth in Scotland, and then on to Caithness for furthur training.

Tommy embarked once again mid 1940, with the Black Watch, aboard the passenger liner 'Athlone Castle' from Southampton for the Middle East. Two destroyers escorted the liner. Nearing the Spanish coast they were attacked by German long-range bombers using bombs and machine guns. The ship wasn't damaged in the attack but the Captain decided to change course, as the bomber crews would have informed their base of the course that the ship was on. A few days out from Gibraltar the ship came under attack again, this time from submarine torpedoes. The ships officer later informed them that 3 torpedoes had narrowly missed the ship. They disembarked on the Rock to boost the defences, and within a few hours were under attack from Italian planes. The date was well remembered by Tommy as the 23rd July 1940 was his 21st birthday. A convent was hit during the raid and several nuns were killed and a number of others injured. Tommy sheltered in a pillbox as yet another attack took place shortly afterwards and bombs rained down but fortunately little damage was done. At this time there was much German submarine activity in the Mediterranean and many allied ships were lost. The aircraft carrier 'Ark Royal' was one of those casualties. Tommy was on duty on the quayside helping with the casualties and the dead, and heard from those who had survived their journey from Malta as 'a journey through hell.' All this time air raids hampered the rescue operations but they had no option but to see it through.

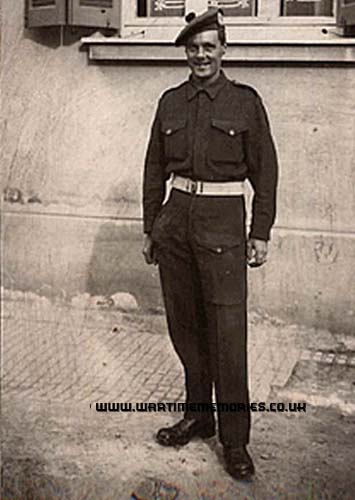

Back home in South Shields, on much needed leave; Tommy and Peggy decided to get married. So on the 25th March 1943 they 'tied the knot' at St Mary's Church, Tyne Dock in South Shields. Tommy was just 23 years of age and Peggy was 24 (see photo above). Sadly, and disappointingly for Tommy, neither of his parents attended even though they were invited. Guests were Peggy's sister Belle and her husband John Watling along with their daughter Joan. The reception was held at the Green Bar at Tyne Dock and music was provided by Isaac on piano and his wife along with others, and a tea was provided at Peggy's mother's house in Eldon Street, which was just a few minutes up the road. There wasn't to be much of a honeymoon though, as a few days later a telegram arrived from the War Office to report back for embarkation to the Middle East. Tommy delayed and eventually turned up at camp just before his unit was about to leave. He was in big trouble. He had to appear at H.Q. and was punished with 6 weeks loss of pay and 6 months confined on other tasks.

He was soon back into the war and arrived at the end of December 1943 for Myrna Transit camp, Port Said, Cairo via the Suez Canal with the 2nd Battalion Cameron Highlanders. By 1944 Tommy was on Italian soil and going into battle at Monte Casino. This battle was not for the faint hearted. Some divisions of allied troops were almost wiped out in the fierce fighting that took place. The death toll was estimated to be about fifty percent of the allied troops and 20,000 Germans lost their lives. The German army had fallen back to defend a line across the centre of Italy just south of Rome. The allied forces advanced up to that line in January 1944 but were held for months at Monte Casino. This was a mountain top monastery overlooking the route to Rome and it was easy for the Germans to shell anything they could see that moved in the wide valley below. There was also a fast flowing river, the Rapido, separating the two armies and many allied troops were lost in failed attempts to take the German position. Tommy can remember long before he reached this area, the smell and the silence. There was no sign of any natural life and everywhere the trees had been destroyed by the shelling. The transport lorries had to be left behind when they reached the foot of the slopes and the soldiers joined the mule supply train for the rest of their journey. From the H.Q.'s in Reserve they were moved to forward positions, sheltering in bunkers known as Sanger’s. These had been built to protect the men from the relentless mortar shells which rained down on them day and night, for weeks on end, and which caused great loss of life. Tommy and his mates were there to relieve a party of the famous Ghurkhas of the 8th Army, 4th Indian Division. Tommy realized straight away that the Ghurkhas were more used to face-to-face fighting than sitting around being shelled. The weather deteriorated and their positions were covered in thick snow and ice for four weeks. During daylight it was impossible to leave the Sanger as enemy snipers were causing a lot of casualties. Only when darkness had fallen was it possible to move about, but complete silence was important, as enemy patrols were present in the nearby area. Tommy went out under cover of darkness on one occasion when nature called. In the inky blackness he caught his tunic badly on barbed wire, and then two days later he realised he had cut his arm and it had swelled up so much that he had difficulty taking his tunic off. That night his temperature soared and he reported this to his Captain who sent him down to the casualty station to get it seen too. The conditions at the casualty station defied description. Medical orderlies were working non-stop treating the wounded and dying in very poor conditions. An orderly spotted Tommy and he got a doctor to take a look at his arm. He was given an injection that knocked him out. When he came round his arm had been seen too and was bandaged up. The surgeon told him that if he had been only a half-hour later in being attended too he would have lost his arm. He was then transferred to another hospital since he was temporarily unfit for duty.

Later his unit was moved down the mountains, to be relieved by a fresh British Regiment. Arriving back at base camp he discovered that his best friend had been killed by a direct hit on the sanger and also that his company had lost at least a third of its officers and men (45 from 120 full company). Their appearance on arrival shocked even the people there. They had grown long beards and were fatigued and hungry. They were instantly given hot showers; their clothing was destroyed and after a hot drink they were left to sleep, which must have been at least 24 hours. The aftermath of this was diarrhoea, sickness and vomiting amongst the group and some men had to be sent to a special camp in Southern Italy for treatment. After discharge from Rest Camp they went back to normal duties. The town of Casino at the foot of the mountain had been the scene of heavy fighting. Troops from England, New Zealand, France, India, Poland and the U.S. were involved. The Ghurkha Regiment 4th Indian Division made many attempts to take the monastery with heavy casualties. Heavy rain caused the ground to turn into a quagmire and the allied tanks were unable to move and heavy skies prevented the use of aircraft. The conditions for the troops were intolerable. It was cold, wet and the shelling never ceased. Food, water and other essentials were almost gone due to non-arrival of back-up supplies. When the skies did clear hundreds of allied bombers pounded the monastery into rubble. The Germans still fought on but the Monastery eventually fell to Polish troops after fierce fighting, forcing the German forces to fall back to new positions. The allies kept pushing north through the mines and booby traps.

Just past Rome, during an attack on an occupied village Tommy was blown off his feet by a shell. When he regained consciousness he was suffering from concussion and had lost his hearing. A medical orderly was talking to him but he couldn't hear a word. He wrote this down on a piece of paper and showed it to the medic. He was taken to a cave that was being used as a shelter where he was injected with something which knocked him out. Tommy had been in hospital for four weeks when one day he became aware that he could hear a nurse talking. After another four weeks recovering he was sent back into action and finally reached San Marino. He was given traffic duties along with an officer, a sergeant and another private. They were to control the heavy traffic moving to Northern Italy that was pursuing the retreating Tadeschi and Italian Forces. At about this time Italy capitulated and called off the war. After leaving San Marino he embarked on a tank landing craft for Patras, Greece where they were to try and restore order amongst the supporters of rival political parties. The Germans had abandoned a lot of arms in their haste to flee and the rival Greek factions had taken these up.

While Tommy was in Greece hostilities against Germany came to an end. There was much rejoicing in the Greek villages and many parties were held, and to which the 2nd Battalion of the Cameron Highlanders were invited. When he first went to one of these celebrations he was confronted with lots of food on the table but couldn't find a knife or fork by his plate. Seeing the confused look on his face one of the women asked him what was wrong. She said they didn't use knives and forks, and took a large carving knife, sliced off a huge piece of meat and handed it to him to eat with his fingers. While billeted in the barracks he contracted malaria and was removed to a Greek hospital suffering a high temperature. He was laid up for four weeks. British, Greek and other medical people staffed the hospital. Later he made his way to Athens before leaving the Cameron’s, who were heading for Palestine, to travel home to England on board the 'Dunnotter Castle'

After a short break back in England, in January 1946 Tommy was sent to Vienna, Austria for Occupation Duty with the 1st Battalion The Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders on general duties as an Assistant Store man. While there they occupied a large building for their barracks. Vienna was split into four areas, British, American, Russian and French. When off duty he toured the City to see the wonderful buildings, visited the opera, the huge ice rink and large cinemas. Much damage had been done to the City. He spent a lot of time at the NAFFI cafe and went to a local dance with two of the lads. While there he met a Hungarian girl who worked at the British Headquarters as a typist. She offered to show him round the well-known parts of the City. She told him she was married and had a little boy. Her husband was on the Russian Front but had been reported missing in action. Tommy offered to make enquiries about him but nothing was heard. After six months was up he was demobbed, and made his way through France by train to the coast.

Tommy arrived at Market Rasen in England and shortly afterwards decided to celebrate in a local pub with his mates. When they went in to the pub the landlord saw their uniforms and told them that they could have what they wanted for free. Having consumed quite a considerable quantity of free alcohol they made their way back to their huts to get freshened up. Tommy was at an open window having a shave when the sash window dropped down hitting him on the head. It knocked him out cold. He can only remember coming round with his mates asking him if he was all right. Once cleaned up they then travelled to Scotland. Could anyone really get back to normal after going through years of deprivation and horror? Anyway, Tommy returned to his native South Shields and got himself a job at a timber yard at Tyne Dock and settled down to lead a normal life with Peggy. He was later employed as a Coal Teamer at Tyne Dock Staiths.

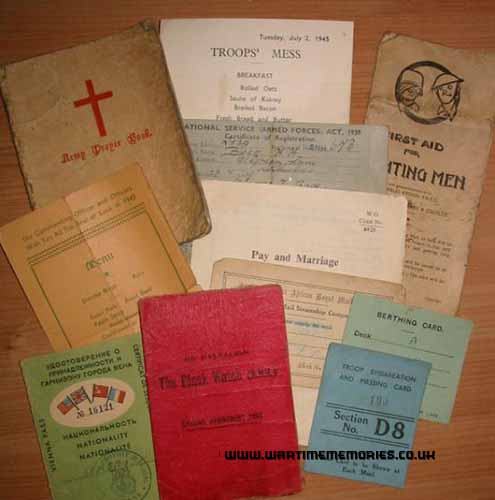

Many years later due to a query from his grandson David, Tommy decided to apply for the medals he had never received. After the war had ended he was just glad to be back home and wasn't bothered about getting the medals he was entitled too. He supplied as much information as he could in a letter to the War Office and about four weeks later a parcel arrived which contained The Italian Star, The Defence Medal, The 1939 to 1945 Star and The African Star. Tommy entrusted these to his proud grandson for safekeeping. As well as having the medals Tommy has kept all the documentation he received, such as passes, menus, ship boarding passes, prayer book & First aid booklet.