Cpl. Malcolm Cyrus "Mac" Adam

British Army 5th Battalion Royal West Kent Regiment

from:Edwards Road, Bromley, Kent.

My father Malcolm Cyrus Adam (Mac) joined the T.A. on 03/05/1939. He attended a camp at Lympne in July and August 1939 (see photos), moved to Bridport in November, and went to Flanders with the BEF on 02/04/1940. He was made a corporal in the 5th battalion R.W.K. on the 15th March 1940 and put in charge of a bren gun carrier detachment. I believe he was the driver of his vehicle, having passed his driving test in Paris in 1938.

On the 26/05/1940 the unit clashed with elements of the 1st Waffen-SS Vefugungs division close to the Forest of Nieppe. Two German units were in the area, the 'Germania' and the 'Der Furher' regiments, but I'm not sure with which they engaged. The following day, the 27th, a German grenade was thrown into my father's bren gun carrier and he was badly wounded by two pieces of shrapnel: His crew, two good friends, were killed outright. I do not know if he was taken prisoner at the time but I would imagine so. (The dates listed on his discharge certificate were written several years later, and do not tally with the dates given on the doctor's description of his wounds written in Enghien)(see later scan).

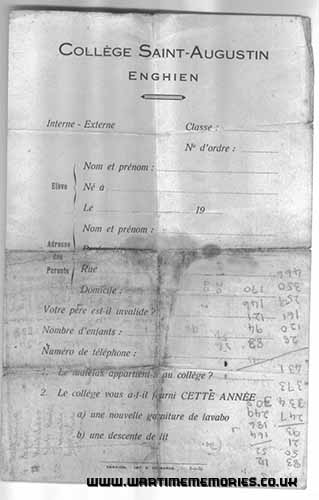

He was taken to a German military hospital, a former sanatorium for handicapped children called 'Le Preventorium' at Marcoing near Calais, known to the Germans by the id.code Kgf.Lazarett II/XI (see photos). He was treated there for his wounds and then allowed to convalesce for the next three months. He had had the good fortune to be registered as an officer and also acted as interpreter as he spoke fluent French and some German. When he was due to be moved to Germany, he decided to try to slip away and but was ill-prepared and was recaptured shortly afterwards, being lightly wounded again in the process. This time he was patched up at the College Saint-Augustin, Enghien, Belgium,(see scan) and moved to Germany three weeks later, sometime just after 03/11/1940, but I do not know where too.

A postcard from his time in Marcoing has three names and addresses recorded on the back:(see scans) Jack Sheppard, 46, Whitmore rd., Beckenham (Beck 1350); Nobby Clark, 16, Hathaway road, Croydon; Alan Cav …(unreadable),86, Southwood Road, New Eltham, S.E.9 (Elt1998). A second photo is marked ‘offizieren’ and with the ink stamped number 482. The third photo also has the pencilled notation Kgf.lazarett Frankreich mai’40 and another name and address: Tony Grafton, 53, Old Steine, Brighton (Brighton 4971)

I believe he eventually arrived in Stalag VIIIB Lamsdorf in early 1941. As far as we know, he was moved around quite a lot between different Arbeitskommandos. Certainly he spent time in E155(see photo), which I cannot find in the published lists, but he spoke (rarely and very reluctantly) about a few different jobs:

He never went into much detail about life in the camps except to repeat the constant hunger. He did mention making an alcohol from a straw mattress and then eating the straw afterwards; also from potato peelings and sawdust. He also talked about grinding acorns and how bitter they were. He also spoke of an occasion when he got away from his guards and grabbed a chicken, alive, and attempted to eat it, feathers and all. The owner of the chicken, a farmer, shot at him: He still had three shotgun pellets visible in his neck, which successive doctors had thought safer to leave in place, right up to his death in 2004.

- 1. A salt mine close to Krackow (from the verbal description I believe this may have been Wieliczka).

- 2. The building of a camp to house female Jewish prisoners in a 'forest'(part of the extended Auschwitz-Birkenau complex). He was very upset about this place.

- 3. A paper-mill (possibly E8, Krappitz). One of the 'easier' jobs.

- 4. A steel works (iron foundry)E138 Ratiborhammer (Kuźnia Raciborska, Poland). He spoke most about this place describing it as hot, dangerous work in very bad conditions and with very little food. (Wilhelm Hegenscheidt GmbH, Hoffnungshütte, making Gießerei, Schweißeisen-Werkzeug, Eisenbahn-Kleineisenzeug, Wagenachsen).

- 5. Blechammer (I. G. Farben)

- 6. Cosel camp (Kedzierzyn-Kozle). He left from here on the long march on 22/01/1945.

He attributed his overall survival to a great deal of luck, an ability to laugh at life and to a certain affinity for languages: His French had given him time for his legs to heal initially, and he had learned to speak German and Polish quite well, which was a big advantage.

He did not like to talk about his experiences other than on rare occasions when he met someone who had also been there, or who had undergone something similar. He told me that he could talk to Denholm Elliot, and he certainly discussed them with his Catalan friend Jorge who had survived the worst of Franco's camps in Spain. He avoided discussions about the march, but he did once tell me that he had twice been the 'only survivor from my group', but I do not know any more about the incidents concerned. The only time I ever overheard him refer to any details was once on the telephone in the 1970's when he was still trying to get his overdue army pay. He was talking to some government official who was still trying to give him the runaround more than 25 years later, and, in exasperation, he told the man just why he felt entitled to his money. Apparently he had done this once before, just after the war, when the British government refused him a passport on the basis that he had been born in Calcutta, India, to parents and grandparents who were Irish citizens and who had missed the date for registration under some sort of amnesty agreement. He won, eventually, after a bit of a struggle, but it left him with an abiding disgust and distrust of officialdom.

He did eventually get paid his back pay, but he was very annoyed that he had to reimburse the cost of some piece of kit that he had been issued with in 1939 and could no longer produce! The amount that he finally received was so trivial by the time he finally got it that he decided to blow the lot on a decent family meal: I think he still thought of food as a top priority and as an appropriate use for the money.

I was quite surprised to find his pencilled itinerary of the march after my mother died, and I have tried to identify some of the places by their modern names, but it still seems an illogical journey. However, knowing how he was and with his lifelong obsession for maps and routes, I'm confident that he would have recorded the names only if he felt sure of them. It is a pity that he annotated so little additional information. He lost several friends on the march, including right near the end, which he thought particularly pointless and sad. The whole experience left him with a hatred of waste, but he also had learned to live life to the full.

He taught me that it was important always to enjoy your day because you might not get another, and by living this way, you would also bring a smile to the faces of those around you. That if you were fortunate enough to have food, warmth and shelter, then you were a very rich man and could easily afford to be generous to others. That if someone asked you for help, even an enemy, you should give it without question or thought to the consequences, as this was true humanity. Above all, never to lose your sense of humour or your sense of wonder - cultivate these and you will always be a positive influence in the world.