A/Cpl. Reginald George Humphries

Royal Air Force 1520 BAT Flight 458 Squadron

from:Wandsworth, London

At the end of the course I was posted to Holme-upon-Spalding Moor, 458 R.A.A.F Squadron and was given a travel warrant and a packet of sandwiches, and dropped at the railway station, along with most of the chaps from the course who were all going to different stations. Some were pleased, some were disappointed with their posting. I was pleased as I was going to a Bomber station; but where it was I wasn’t sure. A visit to the R.T.O.s office soon told me - "Travel to London change to Kings Cross, get a train to Retford, change to Market Weighton and wait for transport." As it was in the afternoon before we left Hereford, I had a quick trip home and was off the next morning to Yorkshire, which I did not know at the time was to completely alter my life, for here I was to meet the only girl for me & marry her.

I arrived finally at Market Weighton station and phoned the camp for transport and after a very long wait, a small open back truck arrived. By now it was almost dark and the ride back to camp in the back of the truck didn’t give me any idea of the area. On arrival, after reporting to the orderly room, I was shown into a hut and found a bed and told to report to the section in the morning. Next day, after having found the way to the dining hall for breakfast, I found the Electrical section and was soon being shown what my duties were to be (when we had some planes to work on!)

The camp was new, and one of the hangers still hadn’t got a concrete floor, and other parts of the camp were still being worked on. The electrical section shared a small work shop with the R/T section, next door was the Accumulator charging room which came under our care, some time later we had specially trained W.A.A.F.s to run the Acc rooms. The section was made up of a Flight Sargent who had been recalled into the service, one Corporal, 2 Group 1 Electricians and six group 2 Electricians. We were split into two groups, A and B Flight. I was on B Flight and with the three Group 2s, we would be responsible for all the aircraft in B flight (when they came) as well as providing other duties like guard duty and night duty in the Acc room, which was shared with the A flight lads. After about two weeks, aircraft started to arrive, and it wasn’t long before we had our full strength of 24 Wellington Bombers spread around the airfield. The airfield had been a farm, and as a lot of the fields were still planted with crops, the farmer was often seen gathering up the carrots, turnips, swedes and other vegetables. He was helped by all the lads who could always been seen munching on carrots or turnips while carrying out their various duties on the planes. Being new aircraft there were often alterations or modifications to be made to them. Some minor, while others quite major, which required the planes being put in the hanger. One of the jobs I can remember doing was the installation of a wiring system for the release of poisonous gases, but it was never used. Eventually the Squadron was ready for operations and work started to get into a routine.

It was about this time that the main body of the Australians arrived on the camp, it seemed strange with their dark blue uniforms at first, but as we all wore dark blue boiler suits when working, we soon settled down together. There was the usual rivalry between nationalities but on the whole we got on well. We had some additions to the section, we had our own Fl/Lt Engineering Officer and six more electricians. A typical days work. began when we arrived at the section and checked on work for the day. This depended on any reports of damage, failure of parts from the previous nights raid, any damage sustained etc. This had to be sorted out and the simple tasks passed out to the Group 2s and the larger ones left to myself and the other Group 1. Although we each had a flight, we often worked together on the more difficult jobs, while the Corporal stayed in the workshop, working on parts which could be brought in for repair like starter motors, generators, magnetos, airscrew motors and regulators. Around mid-day, the number of aircraft required that night would be known, and they had to be inspected and tested. These D.I.s (daily inspections) were done by the Group 2s, who set off round the dispersal sites to check each kite. This required checking all electrical equipment on the plane. Lights internal and external, gun sights, bomb sights and bomb gear undercarriage lights, airscrew, starter motors and ensuring the accumulators were fully charged and often this required carrying two new Accs from the Acc room to the dispersal site. Each one weighed 50lb and after a mile felt like 150lbs. Sometimes you could get a lift from a passing truck or hook them on the handlebars of your bike. There was often a last minute panic when one of the kites developed a last minute snag, which require working until it was fixed; often in the dark, with the aid of a torch held in your teeth or wedged against some part of the aircraft.

As well as these duties, it was also our job to lay the telephone cable between the control tower and the end of the runway, to the mobile caravan, layout the 'Glim' lamps alongside the runway, set up the ‘Angle of Glide’ unit and the ‘Chance Light’. This was a 3kw flood light which was self powered by a V8 car engine driving an alternator, and was switched on as the aircraft were about to land so that it lit up the start of the runway and was put out as soon as they had touched down . There was also the ‘Flashing Beacon’; this was a mobile unit, again self-powered like the Chance Light, but this had a small tower about 3ft high fitted with eight neon tubes which flashed the 'Letters of the Day' and indicated to the crews which ‘drome was which. The flare path 'Glim' lamps were small individual lamps designed so that the lamps could only be seen at a low level, so that the pilots knew where the runway was. Each one had to be switched on or off manually, and was powered by a small 6volt accumulator. If it was misty or foggy, we had 'Gooseneck Flares' christened 'Bloody Duck Lamps' by one of the lads. These were like a large watering can filled with paraffin and a piece of rag pushed down the spout into the paraffin and then lit.

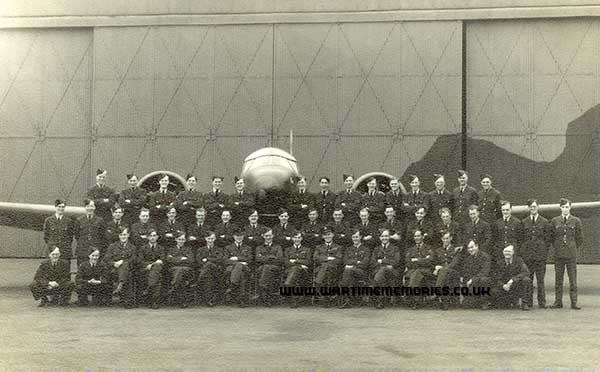

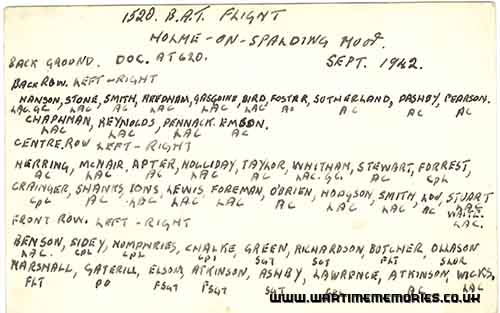

You can imagine the panic trying to put these and the Glim lamps out when a enemy plane had followed the lads home and was trying to bomb the camp. Some nights if there were no operations, there would be new crews doing 'circuits and bumps'; practice takeoffs and landings. We also had a B.A.T. flight on the station 'Beam Approach Training’ and they sometime flew at night. This was an early system for guiding the pilot onto the runway. If he was too far left he heard a series of dots, if he was too far right he heard a series of dashes, and if he was on course he heard a continuous note.

The nearest town was Goole about 15 miles away, and could be reached by a bus service which ran from the camp gates each evening about 6.30pm, and leaving Goole about 10.45pm There were two picture houses, several pubs and on Saturdays they held a dance in the Market Hall. There was also a train connection to Doncaster for the adventurous. Evenings were spent either at the pictures or drinking in one of the pubs. There were several ‘dromes in the area so the place was always full of R.A.F. and soldiers stationed in the area. Occasionally there would be some sailors from the Navy, who sometimes came into the port, but always a number of Merchant seamen, which often resulted in a number of fights.

On New Years Eve 1941 there was to be dance on camp, and everyone was going, but it started to snow in the afternoon and by the time we had to go to the dance, it was starting to get thick. We were met at the door by the Discipline Sargent, and told to report to the stores in our working clothes and a draw a shovel. As Electricians we were sent to our section, as all the station was put on clearing the runway of snow, WAAFs were told to help in the cookhouse making sandwiches, and cocoa which was laced with rum and taken out to the runway. We had to go to each aircraft dispersal and get the small Trolley Accumulator starter units, and bring them back to the section, check them and put them on charge. This was done by a small petrol driven generator on each unit. We finished up with twenty of these things all running through out the night. This system lasted for almost three months - snow clearing squads working every night to keep the runway clear. We were the only ‘drome in the area where a fully laden aircraft could get off, so planes from other stations would fly into us to be fuelled and bombed up, before they went on ops, and then returned to their own stations. We were kept pretty busy over this period, checking each kite as it landed and doing any minor snags which had turned up. At this time we were dropping a lot of sea mines off the French coast and these things were electrically fused; so this became our job to connect them up. This went on through January and into February and of course the wind wasn’t always blowing from the same direction, which meant that we had to rollup the phone cable and re-lay it on another runway. Trying to roll up a cable in two feet of snow was not the easiest of things to do! Usually we had the drum held by two men holding a piece of pipe or a crow-bar and the third man turning the drum to roll the cable onto it. Once or twice it was so cold, the Aussies would have to stop and go back to the section and send two more out to finish the job. One morning one of the Aussies said to one of our lads, “Bloody cold this morning mate”, to which the cockney replied “Cold mate? No it ain’t ..... you wait till you see the penguins flying over here, that’s when it’s really cold”. These lads from down-under didn’t like the extreme cold and couldn’t understand us Brits getting undressed for bed. They often went to bed in trousers, pullovers, balaclavas and even their great coats.

Different from the RAF they had permanent 'Room Orderlies', whose job was to keep the barrack room clean, ours was a rough and ready chap called 'Sharky'. The two pot-bellied stoves in the hut were alway red hot (where he got the coal from we never asked!) he always had a large urn of soup bubbling away on the stoves, which used to cost two or three pence for a mess-tin full, very welcome at night. We never asked where he got the ingredients from, but I am sure some of the farmers may have wondered about their chickens disappearing.

At last the snows went and we could get back to normal working, checking the kites for ops, repairing those damaged or due for inspections. These were carried out every 40 hours of flying time. Every aircraft had its own record sheet, Form 700. This had to be signed every day by the various trades who had worked on it certifying that every thing was O.K. The Pilot would check it and sign it before take off. The inspections got more detailed as the flying time mounted up, a 40hr was relatively small and could usually be carried out at the dispersal site; whereas a 120 and 240 would require being carried out in the hanger; while a 360 would be carried out at a maintenance unit where they had bigger hangers and equipment for taking the plane apart so that certain parts could be tested. A lot of aircraft never lasted to undergo a 360 but the 120 and 240 kept us busy.

We got leave from time to time, usually a 48 hr pass once every six or eight weeks; and a 7 day leave every six months. I went off on a 48 and visited some friends of my cousin’s husband. He had been stationed in the outskirts of Sheffield on the Ack-Ack and had met up with these people who invited Gladys to go up and stay there for a while. She and Dink had married in July 1939 and Dink was a Territorial who were called up in August 1939.

I had a pleasant time and was taken around a steel mill and the man I was staying with was one of the managers and had to visit the works on the Sunday morning. When I returned to camp the hut was empty; everyone had gone - they were on embarkation leave, and I wasn’t on the list, so for a few days I was without a unit and spent time packing up the things in the section that had been left behind. After a few days I was told to work in the station workshops until a posting came through for me. So it was back to looking after the Accumulator rooms and any work on the M.T. section that might come up. By now there were WAAFs in the Acc Rooms, so I only had to keep an eye on things. After a week or so I was posted to the B.A.T. Flight on the ‘drome. We had four Airspeed Oxford aircraft and they flew from dawn to dusk doing circuit and bumps with pilots learning how to use the Beam Approach. Occasionally a strange aircraft would land either by mistake or when their ‘drome was out of action or fog bound, and would need inspecting before they took off for their home base. It was about this time that one night we had an ENSA concert and that is where I saw a very pretty WAAF walking with another girl, and I thought, “What a smasher! I must meet her”, but when the show finished I couldn’t see her, and although I looked, I didn’t see her again on the camp that night.

When the Squadron was on the station we had ordered some equipment for testing generators and voltage control units. They had arrived after the squadron had left, but knowing another would soon be filling their place, it had been set up in the Workshops in the room where they had a large lathe, One day I went into this room to test a generator, and to my great surprise, there bending over the lathe, was the very girl I had been looking for. She was using this large lathe to polish the centre electrode of a spark plug. Needless to say, we soon got talking and before long we were meeting in the evenings. She told me that she and her friend were intending to spend a leave in London, and asked if I could suggest places to see and where to stay. I suggested that my mother might put them up and wrote home straight away, and soon received a ‘Yes’ answer. I suggested that I took a 48 hr leave as well, to show them around a bit. I then changed it to a 7 day leave and as Ivy could leave camp earlier than I could, we would meet on King Cross Station. It was also the day that my name appeared in orders to be promoted to Corporal, so it was round to the tailors to get the stripe sewn on before I went on leave. When I got the Kings Cross, I was busy looking for a WAAF, when a pretty girl in civvies said “Can I help you, Corporal?” Then I realised that it was Ivy in civvies, and I have been in love with her ever since that time I saw her walk into the concert. We spent all our leave together with her friend who had been posted from Holme, seeing the sights and visiting the pictures to see ‘Gone with the Wind’; and finally going back to camp together.

We were kept pretty busy in the BAT Flight. The planes were up every day from early morning until dusk, this meant that the bigger inspections came around much quicker, it seemed that there was always one of the four in the hanger for a major inspection. We would have at least two 40 hour inspections a week, and a major inspection every month, apart from the day to day inspections and repairs. To simulate night landings, the cockpits were hooded and the pilots had to wear special goggles. The flare path was laid out with sodium lamps (Bright Yellow) which they were able to see, but nothing else; and listening to the dots and dashes of the Blind Approach system they had to land on the runway. After every Major inspection the N.C.O.s of each section had to go up on the air test. One day when we were flying, there was a new Radio corporal up for his first time, and one of the tests was to see if the plane would fly on one engine; the look of horror on his face when he noticed that the port engine had stopped...... “We’re going to crash”, he yelled and made towards the door. Someone grabbed him before he jettisoned the door and suggested that he had better put his chute on before he left. We quietened him down and persuaded him that every thing was alright. One of the pilots was a Canadian Sargent, and would let one of us handle the plane for a while. At first it was difficult keeping it level, but after a while we soon got the hang of it.

Apart from the BAT flight duties, I was still called on to keep an eye on some of the other electrics on the camp, like the bomb aimer trainer; this was a two story tower where the bomb-aimers could practice. A bomb-aimers position was on the higher level, while a film camera showed a moving picture on the floor. When they saw the target and pressed the release button, the film stopped and a pinpoint of light showed where the bombs would have fallen.

Reg Humphries