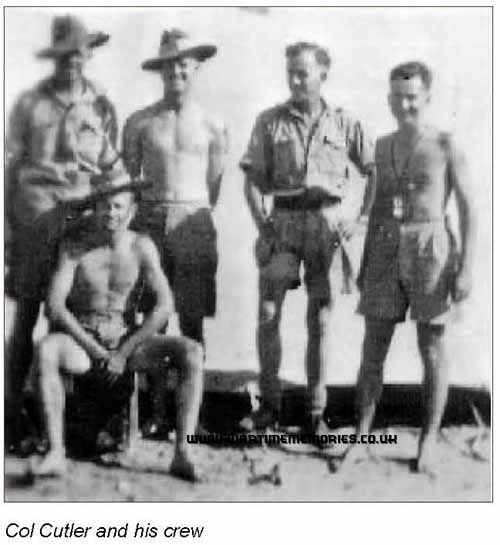

F/O. Colin Thomas Cutler

Royal Australian Airforce 104 Squadron

from:Ipswich, Qld Australia

My father , Flying Officer Colin Thomas Cutler , who serviced with the RAF 104 Squadron in Kauioron Tunisa from 1943-1944 and at RAF Foggia from 1944 - 1945 This history was recorded as a 50th Anniversary of World War 2 project, by the local historian in Ipswich Qld Australia.

My name is Colin Thomas Cutler, I was Dorn in Ipswich and grew up in Silkstone which is near Booval, went to Silkstone School then Ipswich Technical College then started work when I was 14. In those very early years, there were very many famous names in aviation reaching Australia by as reliable a means as they could in the air - which was quite often very shaky. One of them I remember was Bert Hinkler. When he was approaching Silkstone State School, we were all marched out the front and a flock of aeroclub planes from Archerfield flew up to meet him and fly back with him to Archerfield or Eagle Farm - I'm not sure which he landed at. We were all out in the parade ground, screaming our heads off and waving but I don't think he heard us. These people had a very big influence on my attitude to flying and aircraft. The next one I think was Amy Johnson and she also flew out solo from England. When she was landing down at Eagle Farm, she must have been fatigued I suppose, but she landed down wind and didn't have enough aerodrome for the plane and herself and she went through the fence and turned over on the back in a cornfield next door on a farmer's property. She got out of it alright, she wasn't harmed in any way. The next one I remember was when I was standing on the verandah of my old home in Silkstone. At that time, I could look straight out to Ebbw Vale Hill. There was very low cloud at the time and I saw the Southern Cross cut across the railway line roughly at Bundamba very low, it wouldn't have been more than 500 feet, and then turn left to go towards Brisbane, keeping the railway line in sight because if they had got up into the overcast, they probably would have been lost again. Where they were coming from I don't know, I don't know if it was Trans-pacific, Trans-Tasman or a local flight - it must have been from some long distance away for him to get lost like that.

Then we used to go down to Archerfield and sometimes I think they were taking joy-flights in the Southern Cross and they also had a Fordtree motor plane, very much like the Fokker that Sir Charles Kingsford Smith had and it did sound like a Tin Lizzie [motor car] taking off. But anyway, they flew and they got the passengers down safely. Of course there were other people like P.G. Taylor and Ulm and all these people had a very big influence on me as a child. and as I grew up, I became infatuated with flying. So when I was about 10 or 11, I got onto a book called "Flying Aces", it was a little journal that came out once a month, I think it was American originally, but in the middle centrefold they had four current planes and projected planes of that era. Of course, I soaked them up as I read the journal, and got to know them very well, so when I went later into the Air Force, aircraft recognition was very little problem to me. They even had pictures of the original Spitfires and Hurricanes and all those planes that fared so well in the Second World War. Later on, I was on about 15/- or £1 a week wages as an apprentice. As soon as I was old enough, when I had a fortnight's wages, I rode my bike down to Archerfield for an hour's dual instruction on a Piper Cub which was about the cheapest form of instruction I could get - a Tiger Moth would have cost 30/- an hour of instruction. After about eight or 10 hours, I went through the test and I got my "A" Licence in the Piper Cub.

After that, it was getting close to 1939 and I suspected that war was about to break out. I thought, well, having proved that I could fly, I wouldn't have any trouble getting in to the Air Force. But to my surprise, when I first applied down at Creek Street at that time, where the recruiting agent was - where they checked you out to see if you had got enough physically to get in - I found to my horror that, not possessing a Junior Pass through laziness, they rejected me. So about six months later on, they must have been running short of the higher educated trainees and a train came to Ipswich to enrol volunteers in the Air Force. I went down there and I must have conveniently forgotten that I had applied at Creek St , and told them I had never applied before - I don't usually tell lies but I thought I was justified in this case, having already gone to this trouble to get a licence. I thought this was banny, not being able to be inducted into the Air Force.

Anyway, this time, it was one expert's opinion against the other so they let me in. I had to go down to Creek Street to be checked again, they let me in this time. Then during the waiting period of about six months, they sent me educational journals that I lapped up like a blotting paper sopping up ink. I loved everything I studied and once I set my mind to it and it got my interest, nothing was an obstacle to me. I learned navigation, I learned engine handling, I learned aerodynamics and all this sort of thing so in a period of four months, I had gone through all the journals that would normally take 12 months. The man that was correcting my papers said he had had it, he had sat up so many nights, I was shooting them back as fast as he was shooting them to me. He said he couldn't offer me any more, I would have to wait until I went in to the Air Force - which was 3ITS Initial Training School at Sandgate when we were called up. After we had been there pounding the pavement and learning to be disciplined to a certain degree, I was then posted to Bundaberg on what they called 12 EFTS which is Elementary Flying Training School on the Tiger Moths, so we started the flying up at Bundaberg at their aerodrome. But we were only there a short time.

There was one course ahead of us which was 19 and our course was 20. Our course wasn't governed by all the rules of the Air Force or anything else - it was governed by a rule called Murphy's Law. Anything that could go wrong, did go wrong and half of the time it was just planes packing up or just plain accidents. But while we were up there, the Tiger Moths were very kind to us and no-one killed themselves, no one even bent a finger nail in spite of the cruelty we inflicted on those in achines with aerobatics. After a month or two there, we were then posted down to Mt Tarampa Aerodrome near Lowood which was just opening up from a raw paddock which had been mown for grass. The cow pats had all been picked up and put in a mountain on the next property.

The 19 course went ahead of us by train and truck and pitched all the tents, which was very good of them I thought, it saved us a lot of trouble, then 20 Course followed, flying with instructors in the Tiger Moths from Bundaberg down to Lowood. To increase the range of the Tiger Moths, which was only about two hours usually, they put kerosene tins full of petrol and a tube running down and connecting to the other tube which ran into the carburettor. This gave us over three hours flying time. On the way down, when we got near the mouth of the Mary River near Maryborough, there was a fishing schooner there with a couple of men on it. The Flying Officer who was my instructor was in the back seat behind me and said he was taking over and he did a dive on the poor old fishermen. At that time, there was a lot of scare going on with the Japanese being so close and the poor beggars dived over the side, of course the water was so clear, you couldn't tell how deep it was. Anyway he said "Oh, I shouldn't have done that! You had better tell them you did it when we get down there!" I said "Not on your life". Anyway, we eventually landed - I don't know whether we landed at Archerfield to refuel or whether we went straight through to Lowood to the Mt Tarampa Aerodrome and landed there.

We got safely bedded in a tent near the western wire fence and just the other side of the fence on the western side was this mountains. of cow dung which was about 50 feet long, about 12 feet wide and about 12 feet high, stacked in such a way that it was all they could do to stay on the sides of the steep slope.

Well, when we got there, the place was in a pretty rough state, they didn't have a Link trainer, they didn't have even the stores set up properly or anything like that, but we did get flying and to me, this was heaven, particularly on the Tiger Moths, you could have a lot of fun with them. Also you could get in some very awkward situations. A Link Trainer is machine they have in a room, it is shaped just like a box with wings on and in it are all of the instruments that are nom ally in a flying machine. You just pulled it down over your head so you couldn't see a thing outside. On the table where the instructor was seated, there was what they called a crab. It was a little machine with wheels on, it could rotate in any direction and as you climbed or dived or turned, this machine registered it all on an inked red graph on the table and they would set courses for you to fly and everything like that. You were closed off, you couldn't see anything outside the cockpit you were sitting in. Another thing, you had to bank the Link Trainer to turn, just as you would in a normal plane, but not having centrifugal force holding you on the seat, you had to learn to get used to not having the proper feel of the plane and obey your instruments instead of depending on your own feelings, which was to be a life saver to me later on because I really did apply myself to this study of instrument flying.

Well, I did practically every subject that was there, I applied myself to it except I think King's Regulations, I couldn't swallow them. Anyway, in the way of recreation, I had a little Triumph utility, it was originally 10hp but they were only about Shetland ponies by the time I got it. Sometimes if we could get leave, I wouldn't register going out the front gate and people thought I was on the drome still, but I wasn't. I went through the west fence, snuck out behind this "dung castle" I used to call it, to put it between the sentry and myself. I came to an arrangement with the farmer over the road and the old barn that I used to put my little utility in is still there, I saw it when I was up at the 50-years celebration for the Lowood Aerodrome, it is still there. Anyway, he wouldn't accept rental for it because he said "You lads are doing enough, I'll look after it free". Some of the lads had a bad habit, due to the shortage of petrol on the drome. At night the Tiger Moths would come in, they'd be serviced, refuelled and all ready for next day to take off about 5 o'clock next morning when the air was still and you'd get good flying conditions, not to upset the pupil training too much with rough air. But these sneaky types would put a tube in the overhead tank which was on the top wing and let it drain into kerosene tins and walk away. When they thought it was full, they would come back, pull the tube out and put the cap back on and walk away with four gallons of aviation fuel. They put the fuel in their cars which were parked on the aerodrome parking lot, which was silly. I said to one of the chaps who was doing it "Sooner or later you are going to get a plane that you drained the previous night and you are going to land short somewhere out in the paddock, someone out in the blue." He said "oh no, they check it again next morning." I said "I'm not so sure about that. If they notice it is part empty, they might top it up but they won't do it every time. You might get the plane that you drained." Anyway, he never did, he was the one who could get in his car and buzz off and sneak back later on and not get caught.

That's why I put my little bute in the barn across the road. It also had a dual function, if I went on leave, I would sneak out - I shouldn't do these things I suppose but after all it was nice getting a break - sneak out and go behind dung castle, across the road when I thought I was out of view of the sentry and get my little bus and I couldn't drive straight past the guard house so I'd go right up, turn right towards Coominya to the peak of the aerodrome that way and come back along the road towards Lowood. This allowed me to have four or five hours extra leave of a Saturday night. It meant I could leave the Town Hall after an Ipswich dance or St Mary's or the Memorial Hall dance and get home four or five hours after the others, because they had to leave on the last train to Lowood which was about 7 or 8 o'clock at night, pick up Ernie driving the bus at Lowood and from there, out to Mt Tarampa camp. I could leave after midnight, get back and sneak across the paddock and sneak into my tent.

I came home one night late, it must have been about 2 o'clock in the morning, did my usual routine - it was a. dark night with a little bit of cloud drifting across - and I came round the southern end of dung castle and I thought in the dark there was a shadow on the ground but I thought it was just a cloud passing over and I stepped on the neck of a horse. As you know, a horse throws up on their front haunches to get up quickly, he snorted and threw me up in the air. I landed face down on the side of dung castle, being a bit unstable it brought a cascade of cow pats down on me, the horse lunged to its feet and kicked out and I could feel the cow pats being shattered by its hoofs, it nearly got me, turned them to dust which meant I got it all in my mouth and eyes, and it went galloping up the paddock flat chat, pig rooting and snorting and breaking wind in rapid succession - at least I blame it all on the horse - I picked myself up after, I could see the sentry up further looking at the horse across the paddock instead of looking at what caused it to be frightened. I dived through the barbed wire, ripped my jacket and dived into my tent and into pyjamas as quickly as I could before he came down as far as my tent. I was spitting out dung for about three days after . I thought country life does have its disadvantages at times.

It was such as beautiful area to fly over at that time, before the Lake up there was dammed, it was just a lovely big lagoon with water hens and wild ducks on it. In those days, I never stopped to think, I'd go down to shoot up a lagoon as I used to call it, but if you got tangled up with one of those wild fowl with your propeller, that could bring you down. So after a couple of flights, I kept a bit higher than necessary when I went over it. There was another little satellite `dome up towards Coominya pub, near the railway line, I think there was a railway line from memory ran parallel to it. All it had was a cleared paddock with a wind sock on it and I could see all these mounds on the ground and I thought they wouldn't be cow pats, they would be cleaned off the ground, I must go down and have a look at this.

So I went down and landed and I looked up the road and thought, "Gee, that pub's open now, it's just after 10 o'clock, I wonder if I could taxi up there and have a quick drink and come back again." But I thought it would look a bit odd with a Tiger Moth parked outside the Coominya. Hotel with all the horses and sulkies and everything else. So I just got out of the plane and went to have a look at these round mounds on the ground, I think they turned out to be where little black ants had built a soft mound of earth. I walked around to the front of the plane and kicked a few to see what they were made of, whether they would trip the plane up or anything when I was taking off again, and I felt this "tap tap" behind me. What I didn't realise when I landed on this satellite dome that the ground was a little bit spongy and when I got out of the plane, it reduced the weight on the wheel and by the time I walked around the front of the wheel to look at what they were, the plane slightly taxied forward. If I had been right in front of it, the propeller would have decapitated me. So I raced around and got back in again and took off and decided to forget the pub and the drink, so I went back to the drome.

I had another hour or so to do aerobatics so I started my usual routine of loops and rolls and stall turns and all this sort of business, and I went to do one stall turn - a stall turn consists of pulling the nose of the plane up with the engine still pulling and almost on the point of stalling, you kick the rudder over on its left wing and dive straight down and went back the other way in a sort of split circle - well, I didn't realise that the engine was fed by the tank on the top wing by gravity, not by pumps or anything like that and when I got up to a certain thing, I went over a little bit too far that way, and I was almost stopped climbing when the engine cut on me altogether. Of course I was leaning back a bit, which meant the petrol couldn't get to the carbie. It started to slip backwards and instinctively, I slammed the stick forward but going backwards, if you are flying and you push the stick forward, the elevators at the back go down which brings the tail up and nose down in non-nal flight. But going backwards doing that, made it do half an outside loop which meant I was hanging by the straps with dirt flying up my nose and in my face. Luckily I always flew with goggles on and it kept it out of my eyes but it did a half outside loop backwards and then the nose dropped and I got it in a more stable condition. But it taught me a lesson not to push things too far, just to go as far as you feel you have got control of it and stop there. And if you have got the nerve to go any farther, then go.

But with all the brutality we inflicted on these Tiger Moths, there is none of us ever got hurt. I can't understand it. Ken was flying one of these machines one morning, he started to get spluttering in the engine as he was coming in to land and he couldn't make it. He landed in a paddock on the western end of the drome. It hadn't been cleared of all these cow pats, but he managed to land it all right The CO knew that something was going on, robbing the planes of petrol the night before. This was the nearest it came to a nasty accident - and Ken was one of the blokes who hadn't been robbing them. The CO got to hear of it and he had the cars on the drome tested for the grade of petrol that was in them. Some of them were using kerosene with hotboxes on the intakes to vaporise it and all this sort of thing. They did run, but they stank as they went along the road. Others had this great gas converter units sitting on the back which didn't give much power, if you got a big hill you were in trouble. Anyway, the CO had the tanks tested and he found that quite a few of them had Air Force petrol m. them, a higher octane petrol than they normally got at garages. So he didn't just clag the blokes responsible, none of us would dob them inn. , he clagged the whole lot of us and we had to run around the aerodrome with parachutes strapped to us, right around the perimeter of the aerodrome with him in a limousine giving us every razoo he could, "Get a move on". Apparently he hadn't been getting the results from 20 Course that he had from 19, and they must have been given a bit of a ribbing by higher ups about it. He was really wild, so after that, blokes who had been scrubbed as pilots because they didn't have the necessary co-ordination approached him and said "Sir, there are some who are refusing to fly, who can fly and wont. We want to fly and you wont let us." He gave then another test and some of them got through.

We also got a bit of duty at night, in some half-dug gun pits. I had been digging enough up the road during working hours in my job and I'd had enough of that so I just put a fresh mound of dirt on top and sat down and had a rest, keep an eye over the edge of the pit, see if the CO was coming, if he was shovelfuls of dirt went flying out of the hole. Interviewer: So the Air Force men themselves had to dig the gunpits? They were partly dug, I don't know who dug them before we got there. The place wasn't in a state of completion, it was only half complete. But we could train on Tiger Moths, that was as far as we could go but we couldn't do any Link Training at first. Anyway, after that was sorted out and they stopped them using petrol - after that racket was stopped, they put a guard on the planes to stop them getting to it.

The next thing that happened, I was lying in my tent in the afternoon, I heard this bang, bang, bang going on. I got up and looked out and here was a three or four ton truck coming across the drome, not towards the main buildings up the top but across all the half-dug slit trenches and it was giving an awful thumping to this load on the back, it was a big box about one and a half metres square. It was swaying from side to side and nearly overbalancing. An Officer came racing out of one of the trainer huts and made him stop. And he said "Do you know you've got a very valuable piece of equipment on there? That's a Link trainer, everything's tuned up to the limit." The bloke got out and said "Mesh Sir"- he had been sent down to get the damn thing at the Railway Station terminal and on the way out, he stopped at Littman's Pub to have a few or more beers and of course he was well under the weather by the time he drove off from the pub. When he came in, he didn't now where he was driving, he was driving over slit trenches and the Officer said "Stand to attention!" "He said I am sir, it's the drome that's moving". He got a strip torn off him about that. Not very long after that, there was a panic on at Amberley that there was a [Japanese] aircraft carrier out in the ocean and the aerodrome could be raided. The Americans were assembling their planes there, the Kittyhawks and Douglas Dauntless dive bombers and Vengeance torpedo bombers, Airocobras, there was a scatter of planes dispersed from Amberley to our satellite training drome at Mt Tarampa. When the panic started, Vern and all his mates guessed right that there would be such a shem ozzle that the training program would stop straight away. He took a gamble and left one of his mates back at the drome to ring through to a number and Vern and his mate took their sedan car and headed down to Brisbane to have a weekend off on leave, AWOL of course, that's the sweetest leave you can have. That night, we were all paraded out, the rookie trainees, to guard the planes on the dome and I got a Kittyhawk, I would have liked an Airocobra but someone else was detailed onto that one.

I went down in the afternoon to guard it. We were supposed to be relieved every two or three hours with a hot cup of tea and something like that. The American officers went up to the Officers Mess. American messes were generally a dry mess, they didn't have spirits in their messes, but the Aussie ones did. The Officers up there had a club and they had plenty of spirits and stuff. Well of course this was like water in the Sahara Desert to the Americans and the Aussie officers up there entertained them to such a degee they forgot about us poor berks guarding the planes. We didn't want to let anything happen to them, we thought they were helping defend us, we would have to look after their interests. So it looks like the ACTs had a. more responsible attitude to their duties than the officers did that night. I could her them carousing up in the top of the hill there at the Officers' Mess. Later on in the night, the wind started to get keen. I went down in. shorts and a. shirt when the heat was on, I thought this is no good to me, I thought "I can guard this sitting up in the cockpit of the plane, if the hoods not latched tight and locked, I'll sit there." So I got up and did that, I thought "This just fits me beautifully, this is for me - a fighter!' To keep the grass mowed when they first started, Thiess Brothers would come in at night on the bright nights and with a minimum of lights, would get the tractor and the mower going and cut all the long grass on the drome so the next day's flying wouldn't be interrupted. There was a foreman came on the drome and there was a chap name of Donald was on guard duty, guarding generally the whole drome. We had an individual chap on each plane but he was guarding the whole drome. Later on in the night, we heard the old mower going, cutting round the parked planes. Down towards the bottom end of the aerodrome, a foreman came in a rattletrap old utility, you could only get old one then, the Air Force and Army had grabbed all the decent ones, he came in down through the bottom end from Coominya, and started driving across the drome to see how his man was going with the mowing. Well, young McDonald gets up and says, "Who goes here?" in a loud voice, but he couldn't hear him in that rattle-trap old bute.

He called out again and no response, so "Bang, bang", two bullets, he was a good shot, he went straight through the cabin just above the driver's head. Well, the thing stopped with such a jerk it's a wonder the cabin didn't fall off. Of course when it hit, the old cabin was so full of dust and dirt, it showered down on the driver and he came out shuddering and stood still while McDonald said "Why didn't you stop when I told you?" He said "How could I with all the noise, the rattly old machine and the mower going and everything else?' I started to get sleepy during the night and when I heard about this incident with McDonald before, I started making up rhymes about him - "Old McDonald had a gun.. and with this gun he'd guard the drome.... with a bang, bang here and a bang bang there..." I kept making up verse after verse about the progress of the tractor and the poor old driver, the bullet through his cabin. I just hoped I didn't have McDonald on the fence when I was coming in AWOL because he would shoot first and ask questions after which wasn't a good idea in my opinion. I kept myself awake with this until morning and eventually they came down and changed the guard. I don't think the officer knew what he was doing really, if he relied on us ACs to treat things a bit more seriously. Those days we did some silly things.

Later on, there was a prominent Ipswich builder H. Trelour who was building a big hanger up the top of the hill to house the Tiger Moths which stood out in all weathers. He had all the walls on but he didn't have the big main doors completed. I don't know where I was, I think we were finished there and I was posted back to Bundaberg on the Aid Service Flying School on Ansons, much to my disgust because I wanted to get onto fighters. But I studied so hard on navigation and things like that, I couldn't get myself lost. I'd take off on a trip solo across country to Toowoomba or somewhere in a Tiger Moth and I'd be gawking round the beautiful scenery below me, I was really beautiful, and you'd get up towards Toowoomba and land and report in to the flight office, make sure you had enough petrol to get home and away you'd go back home again. But I'd go a different route to have another view to look over on the way back, more to the left of what I came up. All these things must have stacked up against me getting on to single-engine fighters.

Although I snuck in the office and read my report on aerobatics, it had above average and I thought, "Gee that will get me in" but it didn't, the navigation was above average and at that time, the air war in England was shifting from fighters to bombers and of course, a lot of us were exported to England, I don't know why, but I thought I was going to go across the Pacific later on. The old Link Trainer, I used to go up there for hours at a time and I again applied myself pretty diligently to that which was a lifesaver later on when I was over Europe, because I could learn to disobey what my senses were telling me and do what the artificial horizon, the air-speed indicator and the turn-and-bank indicator were telling me were right, not what I felt was right.

We got posted from Lowood, Mt Tarampa Aerodrome, and we went by train back up to Bundaberg. On the way up, we had six or eight of us to a compartment and we put our luggage up in the racks above as much as we could, and the rest we just left on the floor, we were going to sit alternately opposite each other sleeping sitting up. I heard a lot of noise and stamping outside and I poked my head outside the passageway door and I saw someone who looked like my younger brother Mery who was in the Militia at the time. I expected to see tough, bronzed AIF chaps, battle hardened, but they were young kids, honest if they were 18 they were stretching a point. I saw this bloke, there were so many of them, they couldn't sleep longways down the passage, they had to sleep across it. I looked down and I thought one chap was my young brother at first and I said "What are you doing Merv?" I looked again and No, it was a stranger. I said "Are you going to try and sleep like that?" and he said "What else have we got?" I said to the chaps, "Take a look outside, the poor buggers, they're sleeping across the passageway, they cant stretch out. We got all our kitbags down out of the racks, jammed them tight on the floor, left the racks vacant, put the lightest blokes up there. We had three up the top, four or five sitting one side of the set, and two soldiers sleeping down below and two on the seat. We said "What have you got for rations?' The poor young kids didn't have anything. I felt sorry for them. We had been given two great big lots of sandwiches, two slices of bread with Spam and stuff, for us to eat on our way up to Bundaberg to see us through. So we spread them around. They went on from Bundaberg, probably up to Townsville. Anything to get troops up north at that time - this was when the Coral Sea was going on and everything like that. We went back to Bundaberg and I was that keen to get back to the people - Bundaberg is a lovely town and the people in it were lovely too. They didn't let us wander around town of a Sunday night bored to tears, no way, they used to put on an evening supper at the churches and you could have a sing-song after and you didn't have to go to church if you didn't want to. And at 7 o'clock, they held a church service. That got us off the streets and you didn't get into trouble. I learned to dance at Torn Dalton's dances at an earlier age before the war broke out because I knew I was shy and backward and I had to bring myself out. Phyllis [his fiancee and later wife] and I used to go to all the dances around the place and we had a wonderful time in our day, even though we didn't have all the gadgets they have today, we socialised.

Anyway, I had no problem in Bundaberg because first thing, my stomach used to lead me everywhere, the right place I found was Lewis' Cafe, if you ordered a steak and you bit it, it mooed, it was that big you could hardly put it on a plate and beautiful and tender and up above it was a dance hall, that's where we used to go for entertainment, I didn't want to hang out around pubs all the time. I had a pretty good time, the people were so friendly I was invited put to three or four homes and got to know the people fairly well, they are lovely people up there, very friendly. At that time it was getting towards Easter, and I was so impressed with the Easter Eggs they made - Phyllis at that time was head lady at A.M. Johnson and Co's confectionery works which was near where the old Swimming baths used to be - and I sent one down to her, I don't know whether they copied it or not but they could see how good it was. Everything was good there, if you had a drink of lemonade or lemon squash, you couldn't pour it out of the bottle, it was that jammed full of fruit, you had to shake it up.

Going back to Bundaberg after the first session with the Tiger Moths I was standing on the running board of the train with the door open to see if I knew anyone there. I was over 21 at that time - an old man compared with some of the kids there, they were 18 or something like that and they got in. I had my 21st birthday down here where the old Glenville Hall used to be.

We were put on Ansons, the Ansons were a forgiving plane, and once again 20 Course was in trouble, they had Murphy's Law applying. The first thing that happened was after I had gone on my first solo flying in the Ansons, I was doing practise circuits and landings and I was sitting ready to take off when I got the green Aldus lamp from the Control Tower and I started off on the throttle to take off. All of a sudden, there was a red Aldus came and a. Very light firing off and I ground to a stop and thought "What the hell's going on now?" I looked right and left, there was nothing wrong, nothing. Then I looked down to the direction I was going to take off, just over the tops of the trees, and there was a plane. It was going up a little bit and down again and he just came over the top of the trees and cut the motor and dropped it down on the tricycle undercarriage, just cleared the trees, from there on he had the wheels locked and he skidded across just close to where I was scattering a shower of pebbles which I could hear clinking on the metal blades of the Anson's nose and he pulled up. It was Americans going up north to Townsville and their rudder, the elevators had malfunctioned and it was jinking the plane up and down. So they got down low and just tried to judge it, when it came down, they cut the motors, just dropped it in, landed downwind, that's why they landed so fast and had it pull up in a long distance and showered me with pebbles. It didn't seem to do any damage to my poor old Annie and I got off again. But shortly after when I was doing some more circuits and bumps, I was coming on the cross-wind leg to come in for a lanchng when I saw a plane well out, dragging in fairly low and I thought Well he's doing a precautionary landing which will land him on the drome just inside the fence so if you had to land in an em ergency short paddock. But also I noticed another bloke right up directly above him - or it seemed to be directly above him - coining in for a normal steeper landing. And I passed behind I thought to myself, "They're bound to see each other surely." But they didn't. I just got past and turned to the left for my approach to landing when the top plane hit the bottom one and cut the tail fuselage completely through just near the turret. It floated away in the air. The bottom plane buckled upwards, the top plane hit it with its nose and when he buckled up, he was like a brake. The top plane hit the nose down so they were again in the flying position and that way, they glided over the fields - well not glided but came down safely enough - landed on top of the other one which the combined weight was too much for the bottom undercarriage to stand, it collapsed and the bottom plane dug the engines into the soil, bringing it up short. The top plane rolled off and rolled about 50 yards and it pulled up too with the propellers all buckled, engines not working. So they more or less glided in to a landing double deck.

I was still looking to the left. When I saw that first collision, I slammed the throttle through the emergency wire, you could hear the howling noise of the motor and I was moving in the old Anson, such a sedate old plane. I corrected that and I looked out and saw the further one, the bloke Jack get out of the door behind the wing and stand and his other mate Arthur, the one that had the tail chopped off, walked straight out the back, he didn't go through the door. and they came around and scratched their head and thought "How did we do that?" I though "Oh my God, 20 Course again! Murphy's Law." That was two Ansons wiped off for a while. It wasn't very long after I was in a predicament myself through no fault of ours. After I had advanced a bit further in the flying, we had to do blind takeoffs. This consisted of having a calico hood wrapped around the back of your head and spread out and fastened to the dashboard of the plane so you couldn't see out. It had an orangey coloured sodium light on the instruments as it would be in a plane at night, you had to rely on instruments. This day, there was a howling westerly wind. We were taking off in an unusual direction, towards the west to take off into this wind, the wind was about 30 miles an hour, about half the take-off speed of the plane itself. Which meant when you took off, you were climbing fairly steeply before you even got over the edge of the drome, you were getting up a comfortable height. The Instructor taxied me out and pointed me and I set the gyro-compass to the heading I was to take off - when I took off, I had to keep on that and go by the artificial horizon and see what my altimeter said and so on. Anyway, I go bowling down there, open the throttle, must have been doing no more than 30mph as far as ground speed is concerned, but the plane became airborne and just as it got over what I thought would be the edge of the drome, I could see billows of smoke which appeared to be coming out of the right wing root of the plane. I hit the instructor and said "Look!" He said "Get back there fast, try to put it out." I couldn't find the extinguisher, but anyway I got back down. The spar of the Anson goes through above the floor about the height of a chair, only a narrow thing, about 18 inches high. I got back in, I was trying to look down the wing root to see where all the smoke was coming from in case I did get the fire extinguisher. All of a sudden I realised there is a whole lot of wires in an Anson running along the right side of the cabin and the Anson was so old that the insulation had perished and they were shorting out.

In the meantime, the instructor, instead of doing the slow turn around and coming back into wind, he did a fast turnaround to lose height and landed with a 30mph tail wind which meant we landed almost at 100mph. In an Anson, that's fast to land. He had a job holding us down. I yelled out to him and said "It's a short in the side here." he didn't hear me. There was a battery just beside my right foot. I thought I'd disconnect the lead on that, it will break the circuit, that might stop it fizzing. So I tried to undo it, I couldn't, by this time he was on the deck and when I looked up, to my horror, here's a. petrol tanker almost one third of the way on the runway. he couldn't go any faster and get out of our way, we had to do something. When I couldn't undo the lead, I gave a terrific wrench and pulled the lead off the terminal, it stopped the fizzing which meant there was less risk of fire. By that time, I had gone flat on my back on the floor when the lead came away, my legs hooked over the main spar. He really couldn't stop the plane hitting the barricades at the end of the fence or hitting the tanker. so he kicked it around on the ground to the left. At that speed, the oldAnson was shudder, shudder, shudder and the starboard undercarriage collapsed. I was flat on my back with my knees hooked over the thing trying to stop being hurled into the turret at the back, the wheels collapsed and came up right under the plane, through the plywood floor, hit me in the back, sent me sitting upright again on the spar holding on to the metalwork of the cabin inside as it completed its turn sliding sideways. Anyway, we both got out unscathed but it could have been nasty.

I got my wings up at Bundaberg and was posted back down here to get transport down south to go overseas. While I was in Brisbane, I used to get out at Roma Street and walk down George Street to Queen St and go to the Pig and Whistle for one of my favourite passion fruit malted milk - because my stomach always led me wherever I went. General Macarthur had ensconced himself in Lennons Hotels in those years and I went past, I wondered why these trams were banked up unable to go and I looked down towards the Town Hall and here's a great big semi-trailer backed across Ann Street trying to back into the loading dock between the back of Lennons and the back of the Town Hall. He couldn't make it, of course. Instead of Mohammed going to the mountain, he was trying to bring the mountain to Mohammed - General Macarthur wanted to inspect what was on the back of this thing. I went down there. As I said before, my aircraft recognition was pretty good after all those years as a kid that I put in studying those Flying Ace magazines. I looked at the plane and wondered why they were making such a fuss over an old Wirraway for, because I saw the radial engine, but I thought no, the Wirraway is made of fabric, this is made of metal, and I looked closer and I thought "That's not our roundel, that the meatball of the Japanese Empire" so I looked closer - it was sitting on the trailer, the left wing had been twisted back and I had a look inside and it was very strong, all-metal construction and curiosity got the better of me. While he was arguing with the driver, I got up on the tray and started looking in. the cockpit, there was a fair bit of dust because it had crash landed, and I thought it looked a bit small to me and I thought This is the Jap Zero, my God, they had been telling us up at Bundaberg that they couldn't fly above 15,000 feet, that they couldn't see properly, and that the planes were made of bamboo and wire. I thought, "Some bamboo and wire!" and they had cannon mounted on them. Anyway I heard this MP say "What are you doing up there, get down." I looked out of the corner and saw some shadowy figures coming out of Lennons dock and I got down. He said "What do you think you are doing?" I said "I've just got my wings mate, I might have to face one of these one of these days and that Jap Zero is going to be a tough proposition." "Who said it is a Jap Zero?" I said "I do, I'm damned sure it's a Mitsubishi Jap Zero" and he wouldn't argue then, he knew I knew what I was talking about. I thought I might be pushing my luck a bit too much and I started walking up past the tram. A bloke on the tram yelled out "Hey mate, what is that?" I said it was a Mitsubishi Jap Zero. Well all the crowd on the tram came over to have a look at one. They had just thought it was another plane.

After that, we went to Sandgate, 3ITS where we started from, and we went down to Sydney where we were put aboard the, well I called it the hell ship, the Western Land which was a Dutch cattle boat and we went from there around the bottom of Tasmania, some ships had been blown up in bass Strait with mines. It had a cork-screwing action right across the Australian Bight with these combers coming from Antarctic crossways, and we went to Fremantle and then we got on the ship to depart and Vern and Tony hired a car and on the pretext that it had broken down, they couldn't get there before it departed. They were deserting the ship -which was sensible. We left but there was nearly a mutiny on it because they tried feeding us ghee which is an Indian butter and it is sour, stale toast and all this sort of thing, no condiments or anything like that. Anyway we got across to Durban and there was nearly a mutiny in the boat, the conditions, so they said we are going to change to the Highland Grey down at Capetown. We got there, a ship was sunk just inside after we got in, and when I went swimming, I was covered with light machine oil, a golden machine oil. From there, we went up to Freetown and half the crew of the Australian planes dived into the harbour which was loaded with sharks to cool off and they had to be ordered out. Then we went across out in the Atlantic which was glassy calm and I had bought a pair of binoculars in Durban and spotted what I thought was a Fockwell Condor that the Gennans used to spot the convoys and radio ahead to the submarine to lie in wait for us. And sure enough, about five hours later on, after dinner, destroyers came racing in, it was flat calm, and started tossing out depth charges. They felt like giant hammers, hammering the bottom of the boat. Anyway, it didn't knock the bottom of our boat in, but it must have kept the sub down. We had to go right in north of Ireland and pulled into Bristol.

We had to go to train in England, we converted over to Wellington 10s. We flew out to Morocco near Fez and then across to Kairoan in Tunisia where the squadrons were operating. They pinched our plane, they pinched my good leather coat, they gave me a clapped out one to get down to Cairo and we waited in a transit camp there for some time before I was posted back all the way I had come down to Kairoan again and started operating from there. Well at that time, Italy was still in the war. My first operation was against Taranto which was a naval base in the heel of Italy. After that, Italy withdrew from the war. Then I got about 15 ops in when my plane blew up from a hang-up bomb that I couldn't locate, I couldn't see. After I had been in hospital for a while and a short time on communications flight, I then went back to Foggia in Italy near Mt Tidonia, that spur that sticks out on the heel of the Adriatic. It was much harder than what I had been doing over the sea which is fairly free of flack. In one instance, they had an unusual form of defence. Instead of the searchlight probing and trying to find you and bring you down, and the night fighters getting onto you, they just put a sheet of light across this valley and you were silhouetted against it like a big bumble bee on a white tablecloth. And of course, everything had a shot at you then. But we survived that alright and along came Ploesti and I saw these four white hot roundels of something above me. I thought, "Oh oh, there's a Liberator with its turbo-superchargers uncovered - perhaps they couldn't cover them - for letting their gas escape. And I got away from it and a short minute after, there was the lights of exploding cannon shells under the starboard wing and I could se by it and by the retracted wheel, it was a Liberator. Anyway, it flew on, it's surprising how much the old Liberators could take. There were quite a few other places where we tried to get over the Alps in my plane, but I had outsmarted myself. The one I had, where you normally cruise at 1700 revs, I had to use 1800 because they put the fabric a bit too loosely on the plane and it caused extra drag; but it was a new plane, I still got the same miles per gallon out of it so I wasn't running short of petrol or anything like that, I was just flogging the engine a bit harder. But when it came to getting over the Alps, it simply couldn't climb over them so we had to go through them, which meant picking out by starlight where the peaks were and following the snowfield up, almost stalling the plane trying to drag over them and the abyss just beyond them, the blackness just beyond, you dropped the plane's nose. What we were aiming at was very heavily defended and to escape the searchlights, the heavy flack, because I was the bottom plane of the inverted pyramid - you'd have the four-engine stuff up around 15, 18,000 feet and me down around 10 - and of course everyone was picking on us. I dived over this cloud thinking I could get away from the searchlights that had zeroed in on me and everything was letting loose on us and all they did was put the searchlights under the cloud which again made it like a white tablecloth and you were a big bumble bee crawling - you seemed to be standing still actually, you didn't seem to be flying at all. And everything they could, they let fly.. But there was one avenue they didn't put all the flack into and I thought, That's where the night fighters are going to come through, they are not going to shoot down their own. They've got the IFF like we used to have on our plane, that was identification, friend or foe box, that we switched on, our blokes know not to shoot us down (they did sometimes!)

Anyway, I managed to go out this laneway they had left clear but the fighter must have been getting ready to come in at me and we passed that quickly , he didn't have a chance to get a shot at me. I got clear and I said I wouldn't wait for the photo flash picture which we used to let a big photo flash, so many million candlepower, drop the same time as the bombs, we held steady for about 10 seconds, it went off when the camera lens was open and took a picture of what you were bombing, just before the bombs hit. But if it was a very bad situation, I would not wait for that, I would say well, they are going to send a reconnaissance plane over tomorrow, up around 30 or 40,000 feet as nippy as anything, like a Mosquito or a Spitfire stripped down, take the photo of what we have done, a photo tonight won't make much difference and if I thought they had zeroed in on me with the radar, their radar which was pretty good, the Germans were very good with their radar and guns and things like that, you knew when you were over their targets because there were different calibre of defence altogether. Anyway, we got away with that one again so once the bombs had gone and I had used up more than two-thirds of the petrol, I could climb to a height where I could get back over between the peaks [of the Alps] and I could get everything tuned down to the minimum revs and boost and throttle openings to glide more or less downhill back to base. which gave us enough petrol to fill a cigarette lighter after we had landed! There were quite a few near misses. I was getting all stray bomb aimers and odd crews – they were partly finished and perhaps something had gone wrong, perhaps a pilot packed up or got sick or his nerves had gone or something like that and they would have all these odd hods. One time I had a Canadian bomb aim er and after a while, he transferred back to a Canadian crew to make an all-Canadian crew and I got an Australian bomb au'ner Dave. and he flew with me until my ops number was up - the 40 ops was up.

Pete came back one day and he was still shaking and he said "We nearly bought it last night Tom" and I said "Why". He said "We were coming past Maribore and nothing - not a searchlight - nothing! Then all of a sudden, this bracket of four heavy anti-aircraft and one on the middle nearly nailed us, of course some shrapnel through the wing -another split second and we'd been a bit further forward, they'd have got us. " I said "What, did they keep shooting?" and he said "No, just the one salvo, that was it, they shut down". I said "Well, they must have a radar-control geared to the anti-aircraft battery, that's probably what it is. Watch your step near Maribore." I never forgot about it and it just occurred to me as I got near it, I think Maribore was in Jugoslavia and I just got near enough and I thought "By gee, I'll watch for this in case it appeared. I told the rear gunners 'The minute you see a flash of gunfire on the ground - we were round about 8000 feet - yell "Go!" in case I miss it." Anyway, all of a sudden, he yelled GO! the same time as I saw this Brmmm of the gunflash - of course they give you a few seconds for the shells to reach you and down I went. Well, there was one, two, three and the one in the middle, four. The fifth one, I felt the thud on the wing, the geodetics of a Wellington are like a coarse-weave basket and they were sort of diamond-shaped, they crossed each other and below and on top were covered with fabric and this shell must have hit - it don't hit the fuselage hard enough to set it off but it scraped the side of the geodetics, went through the top one and must have malfunctioned. We were lucky. But quite often there were things like that. All our targets were military targets - a lot of people think all we did was terror raids - we didn't. The only terror raid they ever did, they nearly had a mutiny , the crews didn't want to do it. They said pick out a military target and we'll do it, no matter how hard, we don't want to just kill for the sake of killing, we do enough of it accidentally when we can't pinpoint the target, or overshoot or undershoot.

Claude, I met him again on the way home, I hadn't seen him for a while, he said they put him on this thing, he said "I picked out the railway marshalling yards, full of gear to stop the oncoming Russians advancing up the Balkans. He said we got hit just as we got lined up over the target, we all had to bail out. What they did was hold us all together, put us on a truck and run us round the city, with people throwing rocks and everything at us and I thought we were finished, I thought we were going to be lynched. But when the Russians advanced through Sofia I think, the capital city, he said when they advanced through there they released them and let them get back from the internment camp. I met him on the boat coming home and he was a different chap from what I met going over. He was a more or less fun-loving extroverted chap, but he was very quiet when he came back from that episode. He said it was a terrible experience, knowing that they were blaming you for a terror raid which some of them did - but he said we didn't, we tried to get that marshalling yard.

There were quite a few chaps that their nerves went on them. You could tell their character changing - from a quite well-mannered withdrawn chap, he had become aggressive and abusive. The best thing they could have done was ground them because he risked four or five other m en's lives. It don't only happen on a squadron that was in the Ops, it happened as after effects, after they got onto training establishments too. You could do little or nothing for them except try to take some of the load off them, that's all I could do. But I often used to wonder "Is it happening to me, the same thing? Am I imagining people persecuting me, am I doing something stupid in my flying?" I found I wasn't but it did alarm me to see these young people change and actually become, sort of schizophrenic I suppose you'd call it.

One night, we had been training near Ishmalia on Oxfords as instructors, I had been instructing for a month and didn't know how to put myself across to transmit my knowledge to the pupil with what they called patter. I had Jack as a co-pilot with me in the Oxfords and he was as calm as a cucumber, I thought "Gee I wish I was like that". I said to him "I wish I had a voice as clear as yours and as calm as you did instead of swearing when things go wrong, getting het up about it". Anyway, I went up and waited and waited at the control tower and said "Can you find out where Jack is, I was supposed to have taken off an hour ago." and they looked for him and eventually found him in his hut, huddled under his bed. There had been a party going on in the hut across the way and a lot of laughing and joking and he thought they were laughing at him, he had a persecution complex and when I went down to see the dentist the next day, I had to go past his hut and he came around and sidled up and said "Hey, Tom, did you hear the way they went for me last night? and I said "How was that Jack?" I knew there was something wrong by his demeanour and he said "They were laughing at me" and I said "No they are not, Jack, they were just having a party, you know how we are". Anyway, I got a Scots chap later on, Jock, he was quite a nice bloke and a damn good flyer too. But while we were there, they transferred and let us fly on the Sinai Peninsula to get away from the cluttered canal zone and there came in a report that a Boston had gone in with I think a wing commander, squadron leader, a flight lieutenant, a flying officer - they had been shooting up, of all things, just being silly as rookies do, and they asked us to keep an eye out to see where it went in. Well we flew out and we spotted it straight away, the tail floating in the Red Sea and we could see an Air-Sea Rescue away in the distance and radioed it, They could hear us but couldn't talk to us. there was a parachute floating on the water so we circled around that for a while and they came over and picked it up, there was nothing on it, and they never got the men that were in that plane. Interviewer: It must have been a strain doing all those operations? Well, it was, I found towards the end of it, I was glad to see Number 40 come up, it was actually 41, they didn't count the one we got completed and blown up on. They missed that one. It was a strain and we had to do the 40 Operations.

Some of the sights we saw un-nerved a lot of them. One night another nice bloke, a warrant officer, and like myself an Australian, came up to me. I could see the look in his eyes when he got up to about 20 Ops and there was an appeal in his eyes - "Tom help me, do something" - his nerve was going, Well I tried to explain to him what flak to watch out and what to do this and what to do that, what I'd found had been effective in bombing runs. I said not to worry about waiting for the photo flash when it's too dangerous - get out and don't worry about the damn photo and all that sort of business, I said your crew and plane's more important than a photograph, I said they'll get that tomorrow anyway. I was standing this morning, taking off down the runway and we were on a slight rise where our mess tent was, I was standing outside drinking a mug of tea after finishing the evening meal and it was still daylight, I could see the top half of the plane and I didn't realise he had a 4000-pounder bomb on because it couldn't be carried in the long bomb bays, where the normal 250 - 500 pounds were put into, it had to be carried completely out of the body of the plane and it was more or less exposed to view. A 4000-pounder bomb was just like a huge black boiler filled with explosive, it just gave a blast effect more than penetrating.

Anyway that was the plane I'd had the previous night and I found nothing wrong with it and he went barrelling down the runway and as I saw him lift off, I could then see it was a 4000-pounder. Then there was a shudder as the starboard engine faltered with a full load of petrol and a 4000-pounder on and simply couldn't maintain the height and of course it went in and there was an enormous explosion. I was standing about half a kilometre away from where it hit and it was just like two great big sledge hammers hit me on the chest and the back at the same time, the concussion. Of course they didn't find much of them or the plane, it just disappeared in pieces.

The next night, one pilot refused to fly, I knew he was going to pack up because his nerves were going, and he was a big strapping chap, I thought he could go anywhere. He got up as far as nearly getting in the seat of the pilot in the plane, and he fainted and fell back down through the hatch. After that, he had to give it away too so there were two crews unmobilised because of that one accident, because they could actually see what could happen and this upset quite a few of them, they didn't go the full distance, they went to about 30 ops, some of them just flatly refused to fly. With some of them - I don't think they should have done it - but they put LIVIF, Lack of Moral Fibre [on their record] and it meant a polite word for coward. Some did actually deserve it, after all that training, they jibbed out but I think in a way, they did the right thing, if they felt they couldn't see it through, they were only endangering themselves and their crew.

There was five in our crew and in a Liberator or a Halifax, they had seven. But of course they had four engines, they could get higher and go further. When the Warsaw uprising was on, they had the Wellingtons on standby, I didn't understand why, but the CO told us when we had a briefing, "Look, the Wellington cannot reach Warsaw from here, on a normal tank of petrol we had to put overload tanks in which go in your bomb bays, that means you cannot carry any relief supplies for the Poles." I said "Well, why can't we just divert to the Russian drom es which is just a few miles away and land and refuel and get more supplies to drop to the Poles and come home or go back and forwards from there." He said "What do you think we are trying to do" he said "The buggers won't come into it, they just sat there and let the Poles be slaughtered while they were fighting the Germans, they thought they could save their city and have a bargaining point for Poland." Well that wasn't the Russians idea. at all, they wanted their.. everywhere. So we were on standby for a couple of nights but the Liberators and the Halifaxes could reach it and they took an awful beating that night because they were shot at by the Germans when they crossed their lines, shot at by the flaming Russians when they staggered across the line and in their fury and frustration, the Poles even took a shot at them, thinking they were enemy bombers. And half the supplies didn't land on the Poles, they fell into Gentian hands. But the Russians deliberately sat there, they wouldn't move or take the pressure off the Poles, they didn't want the Poles to save their own city, so in one way, we were lucky being on standby because we would have been butchered. The only way we could get there and back was to land on Russian controlled territory, refuel and go back, probably drop supplies and come back to base.

One of my mates from Ipswich, Fred Clayton, I didn't know at the time but he was on a drome nearby and I think they must have flown into the hills of Mount Vidonia, that's the hills further into the heel of Italy that sticks out into the Adriatic and he was gone. I didn't know about it, we were only a couple of miles away. And I got a letter from home before I finished my Ops a friend of mine Des, missing over Germany, he was killed there. And Bill Hurley, another one gone, I was getting letters from home and hearing about other mates going and I think, this can't go on for ever, I became very fatalistic, I wouldn't dwell on it, but I wasn't like a man at all, I was like a robot, a calculating robot, what chance is that.

And I had some very strange experiences, there too, the time we went through the mountains, the target was so hot and in spite of all the manoeuvring and things we did to escape the flak, the lights, the searchlights, and when we blew up on the plane, I seemed to reach a stage where my consciousness stepped outside my body and I was looking down at this poor wretch doing things to try to escape death., and fires and things like that, I could see things flying around and opening escape hatches, eventually I sort of withdraw back into my body Well the same thing happened the tine e we went through the Alps, they gave me such a pasting that again I withdrew from my body and Dave, the Australian bomb aim er, sitting right beside me, when I looked closely at him, even thought it was icy cold, his brow was all in a sweat into his eyes and I thought, well I must be going troppo too with this tension and strife But there seemed no way out other than death at that time, and I was looking down at this poor wretch there, twisting and turning and diving. I noticed as I came away from myself - later on I thought, well you're just hallucinating - and as I rose up out of my seat, the long bonnet of the plane, I could just see so far ahead past the gun turret, but as I rose out and got higher, I could see down in front, and I couldn't make this out, what was going on. The next time was when we were going after some tank works - I think it was Ploesti -- anyway I just forget the name of the place but it was where the light was right across the valley and there again, we were like a moth pinned to a sheet and we didn't seem to be moving. I knew they must be. Again, I sort of withdrew from myself, watching this poor wretch in. the control, trying every trick he could think of in the book to get through this curtain and get on to the target. Eventually I sort of went back into my own conscience and was using my own eyes, instead of the eyes of this apparition whatever it was and I said to Dave after I got back, "Dave, when we were over that cloud, did you experience anything?" and he said "Yes Tom, I felt like an icy-cold blast and yet the sweat was falling in my face" I thought, "It must have been something".

After I came home, of course, I forgot about it after the war, but then one of the wife's Woman's Weeklys, I was reading through it and here was a nurse up in New Guinea hit by a bomb splinter and she was clinically dead and yet she recovered later on but she could tell the ambulance bearer everything they did while she was clinically dead. She said she stood outside her body. I thought well gee whiz, it didn't only happen to me, there must be something there.

This is the strange things that happen. A bloke about to break would get a persecution complex, I didn't dare talk about it while the war was on, they would probably think I was on the verge too. But I think my love of flying carried me through. No matter what happened, no matter how many engines blew up or how many near misses we had, I could get out of one plane and get into another and take off again.

Interviewer: Before, we just glossed over the bad accident you had, Could you tell us about that? We were still operating from Kairoan in Tunisia and we had had a successful raid on a military drome in Italy. We had these giant Messerschmidt gliders, they called them Goliaths I think, but they were about as big as a Jumbo jet and they could carry tanks if they could get a powerful enough plane to pull them. That raid had been successful but we came back and we had used anti- personnel bombs which were a new form of anti-personnel bomb. The other ones used to have a long projecting rod on them and if you bumped it, it would blow up. The idea was, when they came down to the ground, they hit the ground and burst while the bomb was still above it and scattered the shrapnel to hit troops on the ground, but they were having so many accidents with them, they brought out a new type which had a blunt nose with a. diaphragm of brass or copper across, and covering that was a coarse propeller with a cap screwed on to cover it so it wouldn't go off and through that, a locking pin that wouldn't let it spin. off until you were ready to let it go. But they weren't carried individually, they were carried in inverted U-type canister which we had to bring back, we couldn't bomb that away, we couldn't jettison that. And across the bottom of it, there was a pyramid of three - two and then one on top - and they a short wire with a. wire piece locking the propeller so it couldn't spin off and become active until it fell out of the plane.

Well, I think what must have happened, was two previous nights, George the bomb aimer had told me on the two previous trips that there was a 250- pound bomb hanging up on the particular point. He said I can't release it, I tried everything, I can't release it." I said "Right George, open the bomb doors, I've got a toggle here, I can jettison, I'll put a powerful current through. Well I pulled the toggle and the 250-pounder bomb was released. George closed the doors, he had inspected them with the light on, "Right Tom, she's right." Well this night, he told me everything was alright, but he couldn't see up inside the thing. And there must have been one up hanging there by the safety wire. When we landed, the automatic pilot was out and I had been flying for about seven hours and I was really tired, it was getting one after the other, these raids, and it was telling on me. I wasn't having the automatic pilot to relieve me a bit. We came and landed and I bumped a bit. I think what that must have done was release the bomb, it rattled down to the bomb doors. That was alright while the port engine was going, it kept them closed. But we had to divert out into what we called the "Bundoo" - out into the paddock a bit - where there was tussocky grass, Of course, I couldn't find out where the aerodrome control pilot was indicating us to. George opened the door "I said "You'd better go down and open the access doors George and drop down and have a look and see if you can spot him." he said Yes, there he is over there Tom" Well I started to taxi, well I thought I was taxiing slowly and there was George taking giant strides calling me for everything to pull up. George hopped back up, but he didn't close the doors which he didn't have to do, we had finished for the day. Anyway we pulled up and I stopped the starboard engine and from what I can make out, you didn't just cut the switch, you had to pull up a. cut-out on to stop the starboard engine OK. I went then into the port engine controlled all the hydraulic pumps and things which closed the undercart, the flaps and all that. I pulled that one up and I was reaching like that and there was this awful flash of white-hot heat came up through that door. If they had have been closed, it could have saved us a lot. It hit me fair in the face, I could see the flesh peeling up in front of my eyes before they blurred from being scorched. Anyway, I managed to open the top escape hatch. Of course the bomb had punctured what remained of the petrol tanks, spilled it on the ground, it was blazing away, and coming up through this open access door.

So I thought, I cant go out there, I'll have to go out through the top. So I threw the top things open and when I put my hand on the fabric outside, they just skidded off because as you know when you throw hot steak on a barbeque, all the fat turns to grease and I couldn't hold anything or do anything. I could barely see because tears from the burns in my eyes and I fell down to the wound, about 12 or 15 feet, went flat on my back in the fire, I stood up but the heat from the fire had started, even though the switches were off, the propeller had started to slowly turn. it hit me and threw me back into it again. But I had a heavy flying suit on and this protected me. Anyway we got up, I got away from the plane and the bloke in front of me started his engines to get away from my plane in case it blew up again, and he nearly ran me down and I sort of look where he is through bleary eyes, I got my hands up but they were useless, all burned. Then I looked back and I saw someone crawl out of the access opening.

[There was a problem with the last couple of minutes of tape. The following is added from notes provided by Col Cutler] They took us to the Burns Unit at Carthage in Tunisia. My hands were all bandaged and they put gentian violet over my face. We were there for more than a month and I had skin grafts. Some of the crew survived: Lloyd, my wireless operator, was hit by shrapnel in his right eye. he managed to drag me away. Lloyd is still living at Wentworth Falls in New South Wales. Allan the navigator, was an English chap, he copped the full force of the flames. His face was badly burned and he died later that night. Bluey was the rear gunner. He just had to tumble out of the rear gun turret and he was alright. But while the rest of us were in hospital, he was then assigned to another area. The plane was hit by flak. He only had a Mae West and Bluey didn't survive. I went to convalesce in Algiers, then went to Naples -the photo of me was taken in Naples after I got out of hospital - it was taken to show my family I was alright - you can see my hands. Then I was put on light duties in Communications. I couldn't fly as normal because the skin on my hands was so thin so they put me on the Beechcraft Buccaneer - a sporty little thing, and I used to fly the top brass to conferences.

Mr Lloyd Jones read a draft copy of Mr Cutler 's interview and sent the following letter which we felt should be included with Col's own wartime memories. Note that Mr Cutler's name is Colin Thomas but he was usually called Tom by his wartime friends:

I feel the readers of Tom Cutler's memoirs should be made aware of Tom's solid character. My association with him began in the Operational Training Unit when I, as Wireless Operator Air Gunner, teamed up with a navigator, bomb aimer and rear gunner to form a crew. I can't recall Tom ever being angry, sarcastic or overbearing with us. He had that in anner about him which made us accept his decisions with confidence. He kept cool in tight situations which developed as we ironed out the problems of learning to fly together. We had several narrow squeaks at the O.T.U. at Moreton-in-the-Marsh. He never shirked his job. After the accident, he did all he could to regain full mobility of his fingers and hands and so be fit for more ops. When questioned on his feelings about flying again by the medical psychology officer, he said he was quire prepared to resume ops. Bombing runs did not have to be pressed home but his did, though he never took unnecessary risks. I feel my survival could, to a large degree, be due to those qualities described above. Lloyd Jones, 23rd July 1996