L/Cpl. James William "Jack" Heslam

British Army 9th Battalion Manchester Regiment

from:Craven Rd, Darnall, Sheffield

Despite good results in his lower school certificate money was tight and the family could not afford for my father, James Heslam, to stay on to do the upper school certificate exams. Dad had, therefore, left school aged 16 in 1935 and was working in the City Clerk's office at the Town Hall in Sheffield in 1938. This was considered a real step up in the family as he was the first member in a couple of generations not to work in the local pit at Orgreave or in the steelworks. His father, George, had been a steelworker but in the late twenties went to work for the LNER as a shunter and coupler.

When it became clear that war was likely in 1939, Dad, known then in the family as Jack, volunteered for the militia and somehow ended up in the 9th Battalion, Manchester Regiment. In May 1940, after his basic training, he was shipped off to France where his battalion was part of III Corps in Lord Gort's BEF.

Throughout my life Dad never really talked about the war however, I knew from my mother that he had been in it from virtually day one and had been on board the HMT Lancastria when it was sunk off St Nazaire with huge loss of life in June 1940. He had then ended up in 1944 as a Captain in REME commanding a beach recovery workshop unit on Sword Beach after landing his hundred men from a RHINO on D-Day plus 3.

In the mid-1980s he had retired from his job as Superintending Civil Engineer for all NATO airbase construction and maintenance projects in Britain and Western Europe and was living in Framlingham in Suffolk. I was visiting my parents for the weekend and, prior to dinner on a nice summer's evening, he and I had gone down to enjoy a pint or two in a local pub garden. Somehow, and I can't really remember how, the conversation got onto Dunkirk and, as he was in a mellow mood, I began to ask him questions about his experiences in 1940 and how he had ended up on the Lancastria.

To my amazement he told me this whole bizarre and fascinating story. He was a 21 year old lance corporal and, when he took up the tale, his platoon of the 1/9th Manchesters had somehow been left behind as part of the rear guard (the rest he thought had made it to the Dunkirk beaches) and all that was left was another lance corporal, a sergeant, a lieutenant and 20 odd men. The platoon was dug in either side of a road and there were other British units on their flanks. They had a couple of machine guns (they were a machine gun battalion) and a Swedish-made Bofors gun for anti-tank defence.

After a nervous night with his section on one side of the road, the dawn arrived and Dad became concerned as time wore on that they had had no visit from the sergeant or lieutenant to update them as to the situation and their orders for the day. Eventually he sent a runner to the section on the other side of the road to find out what was going on. The runner came back accompanied by the other young lance corporal who said that he had not seen the sergeant or lieutenant either. A quick search of the area ascertained that the 10 ton truck had disappeared during the night along with the Bofors gun and the two senior men!

Dad then went in search of neighbouring units. A British officer of another regiment told him that the evacuation via Dunkirk was over and that there was a general retreat westwards and that it was best to get going now. When Dad pointed out that their only means of transport had disappeared during the night, the major told him that his unit only had enough transport for themselves and basically it was every man for himself. Dad returned to his position and the 20 young men discussed the situation amongst themselves. They were on foot so it was obvious that any decision would have to be made very quickly. Dad pointed out that it was logical that the Germans would be swiftly trying to capture and close down all the channel ports to the north as soon as possible and that their best bet to evade capture was to travel straight southwest where there were still, hopefully, considerable French Forces and their own lines of communications troops.

In the end, Dad, the other Lance corporal and three or four of the men opted to go south westwards, the others went North and he thought that they were probably captured and became POWs. Some days and nights of marching then ensued. Having somehow evaded the Wehrmacht, Dad's group eventually came to a large river (the Seine?) where from a distance he could see that the bridge was being prepared for demolition by what appeared to be British troops. Dad went forward cautiously with one other man and a white handkerchief tied to the end of his Lee Enfield which he waved over his head. When he was about 75 yards from the bridge, a call rang out of "who goes there?" He shouted back "British soldiers" and received the reply "advance British soldiers!". He walked gingerly towards a well-armed group of soldiers who had appeared from the sides of the bridge and was about 30 yards from them when an astonished cry went up in broad Sheffield "bloody heck it's our Jack!" He and his companions had stumbled into a unit of the Pioneer Corps and sappers tasked with blowing the bridge and amongst them, amazingly, was Pembo Pemberton who for years had been the deep fat fryer man in my great grandad's fish and chip shop in Darnall, Sheffield. Chaos and confusion was everywhere, the German army was running rampant, the fall of France was imminent and amidst all of this Dad had bumped into an old acquaintance from down the road!

Pembo, a corporal, was around 40 and had served in the 1st World War infantry and had volunteered again but, at this advanced age, only the Pioneers would accept him. Luckily Pembo's unit did have motor transport and and some spare spaces which is how Dad and his fellow Manchesters made it to Saint Nazaire on the fateful day of 17th June 1940. Dad described that they got on board the Lancastria fairly early in the morning. It was berthed quite far out in the sea approaches to the Loire estuary a distance of some miles from the St Nazaire harbour and they were ferried out in small boats. He said how impressed he was with the organization and calm efficiency that greeted them. Each man as he boarded was handed a card which designated an area in which they were to be berthed on the ship. Amazingly, they also managed to get a hot drink and breakfast which after the privations of the previous two weeks was a total godsend.

On board the Manchesters stuck together. Over the next few hours large numbers of troops, RAF and even British civilians were ferried out to the ship which stayed fixed in the same anchorage point. High flying aircraft were spotted at various times although what they were and belonging to which side was difficult to tell. In the afternoon the first German raid came in which resulted in a ship nearby being hit. At that point a conversation ensued amongst the Manchesters about who could swim and who could not in their group. Dad who had learnt in the Sheffield municipal baths and who was an excellent athlete (he went on to play for the Army at football and was offered a professional contract by Sheffield Wednesday whilst at University after the war) was a strong swimmer. Three of the others could swim and two could not. For the non-swimmers Dad described the rudiments of staying afloat in the water, treading water and the basic breast stroke. It was agreed that in the event of an abandon ship they would stand no chance of staying afloat long in their heavy khaki uniforms and it was decided that they would strip down to their underwear, strip out their Enfield bolts and heave their 303s into the sea before entering the water. Whatever happened they would stick together.

When the fateful attack came in at about 3.50am they were below decks. There was a large explosion that completely rocked the ship which very quickly began to list to one side. Dad said that it took several minutes to work their way up to the deck. When they got there it was a chilling sight. Men were cramming into overloaded life boats some of which were stuck at crazy angles and swung precariously as sailors struggled to lower them and others were jumping overboard seemingly oblivious to the wreckage and the swimmers already in the water.

The Manchesters stuck to their plan however and stripped off their uniforms and jettisoned their rifles and bolts. Down to his underwear, Dad had the presence of mind, to hang onto his paybook which he shoved next to the family jewels thereby ensuring that, if he survived, he had an undisputable record of what was owing to him. As the Lancastria began to list further to one side they managed to lay their hands on a length of rope which they tied to the deck rail. As the list angle of the ship had got noticeably worse there was no point delaying and the swimmers (apart from Dad) lowered themselves first. Dad repeated his advice re the technique for treading water and swimming to the non-swimmers and then lowered himself down the side of the ship so that he was waiting for them in the sea as they in turn clambered down. Fortunately, the first one cracked it straight away and managed a serviceable doggie paddle to draw himself away from the stricken ship. The last man however couldn't manage to swim but he kept calm and, with just him to worry about, Dad managed (swimming on his back) to drag him a decent distance from the ship. After about 20 minutes during which some of the other swimmers helped Dad keep the man afloat, they were both hauled on board a rowing boat manned by two French sailors. They then rowed about picking up others. One of the first they picked up was the Lancastria's Captain, Rudolph Sharp. Eventually, with a full complement of rescued men and with a growing slick of fuel oil marking the demise of HMT Lancastria, they made it back to the safety of the harbour.

Dad said that he and some of his other Manchesters made it back to Plymouth on board a Royal Navy cruiser or destroyer and even that wasn't in great shape apparently, so they were rather relieved to get there. Once back, there was no time for post-traumatic stress counselling, the British Army was being hastily and urgently reassembled and after a night in temporary barracks, new uniforms were issued (they all only had a blanket and some underwear!) along with rail passes and orders to return immediately to the Manchester's barracks in Ashton Under Lyne. Dad for one had not been in touch with home for weeks and since all their parents probably thought that they were dead, it was decided jointly that they would all try to get home for a couple of days before presenting themselves at the barracks.

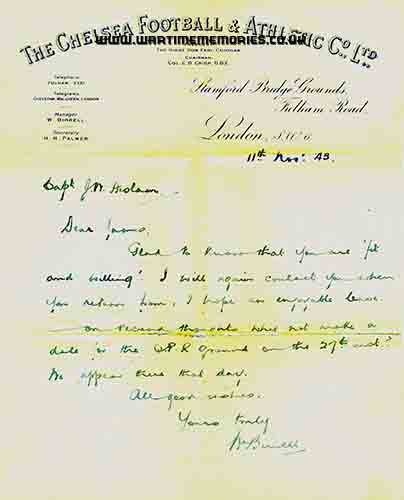

According to my mother, who I spoke to later that night, some of Dad's section had lobbied hard for him to receive a gallantry medal but as there were no officers present to back up their accounts, this apparently, was not possible. However, shortly afterwards, after a spell as a Corporal and a Depot Training Instructor, Dad was put forward by the regiment for the Officer Cadet Training Unit from where he graduated Lieutenant. During that time, he had also impressed a certain Sergeant Tommy Lawton (the PTI at his OCTU and, incidentally, the Everton and England centre forward) with his footballing prowess and ended up playing with him for the Army at a number of First Division football grounds in wartime exhibition games. Pembo had survived the sinking as well and, via the magic of the internet, I stumbled upon his written reminiscence (penned in 1947) a few weeks ago see: www.royalpioneercorps.co.uk/rpc/history_lancastria.htm.

After Dad died in 1998 Mum told me that his mother, Lily, had received a letter from the soldier that he had kept afloat for so long. This was the first that Granny had heard about this as, when Dad had returned home for a couple of days en route to Ashton, he had skated over the sinking of the Lancastria as he didn't wish to alarm his parents. Incidentally, the man he had saved died a few months later out in Singapore where he had been shipped as part of a Manchester Regiment reinforcements cadre.

.jpg)