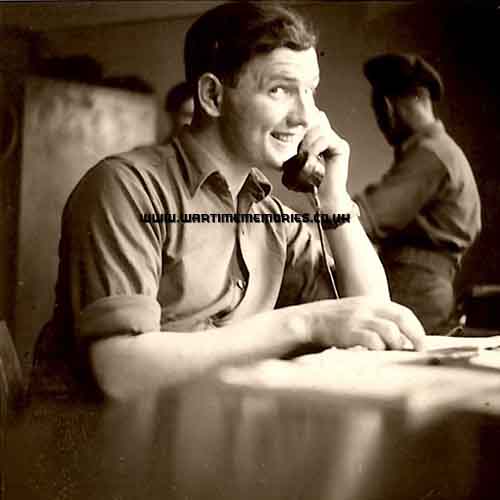

Gnr. Brian Homer

British Army 41st (NSR) Searchlight Regiment Royal Artillery

from:Woodville Road, Hartshorne, Burton-upon-Trent Staffordshire

This is the story of my father, Brian Homer. He has told me stories about the war and when I discovered this site I suggested he shared them with you. His memory is magnificent for someone who is 93. First he wrote me a list of all the main places he visited. Then he wrote the whole story over a period of months. This must have been very difficult for him as he suffers from Macular Degeneration and can only see one word at a time and even that requires a magnifying glass.

This is his story.

War Memories.

England - 3rd of September 1939. 'The day war broke out' to quote Rob Wilton, I (14years old) was travelling in the car with my dad. He said to me, 'You'll be in the war'. How right he was.

June 17th 1943. Primary Training Lincoln.

On a nice sunny day I went by train to Lincoln, arriving at the Primary Training Wing, an army barracks half a mile behind the Cathedral on the right of the road going north. On the left-hand side was the disused racetrack. Horse racing had finished years ago. We did our field training on the course.

The barracks were brick built and called Belisha Barracks. There were two regimental brass bands at the camp: The York and Lancs, whose regimental tune was The Noble Duke of York. The other band was the Sherwood Foresters whose tune was The Lincolnshire Poacher.

There were 36 men in my group, 6 of whom could neither read nor write, so it was left to the others to read their letters to them or write their letters for them. One day, we were sent to line up outside the medical room for an injection. An orderly with a iodine soaked swab came out and started to go down the line cleaning an area for the injection. One of the men, well over 6 feet tall, fainted as soon as the orderly touched his arm.

Every evening at Lincoln, we could hear the Lancaster Bombers taking off from the airfields around Lincoln. One could not help but wonder how many would fail to return. Part of our training was learning how to throw a grenade. We each took it in turn to get into a trench with the sergeant and throw a grenade at a wooden post some distance away. One man fumbled his grenade after he had pulled the pin and it dropped into the trench with them. Luckily, the sergeant moved quickly enough to get the grenade and throw it out of the trench before it exploded.

After two months I was posted to the 228th Signal Training Regiment. I learned to drive passing my test in a lorry on the 6th Sept After a month we were posted to the 52nd Signal Training Regiment at Congleton on August 8th.

Congleton 52nd Signal Training Regiment.

I was billeted at the Marsuma cigar mill which was next door to an open air swimming pool. Previous to our arrival the billet had been used by a group of Dutch soldiers. My friend here was Frank Weston a cinema projectionist from Nottingham. We learned Morse code, operating the No.19 wireless set, wireless procedure, telephones, driving instruction and all about vehicle engines from an Instructor from Rolls Royce. The No.19 wireless set was noisy as it was rotary powered. After six weeks of instruction we were moved to Whitby.

Whitby.

Sept 1943. I was billeted in 5 Church Square, an ancient terraced house. All the space in the building was taken up by beds. The Commanding Officer's name was Major Lockhart, a smallish, pale faced man with a thin black moustache. He gave us a lecture on our arrival. He said there was a Bofor anti-aircraft site nearby (I never saw it) with 300 ATS. He said to remember that some of them are officers. Mary Churchill the PMs daughter was to train there. A Tiger Moth plane used to fly over the sea, just off the coast, towing an air sock as a target for the guns. I never did find out where the guns were.

Our dining hall and training room was in the Hotel Metropole. A large hotel, of some 5 or 6 floors, situated on the sea-front. The gym was in the ballroom. A big, old, dingy building also on the sea-front. We continued to speed up our Morse reading and we laid some telephone wires on the Yorkshire moors. I went home on leave before Christmas 1943 and returned feeling ill. Three days later on the 21st December I was admitted to Whitby Isolation Hospital with Scarlet Fever. I had to give the large treacle pastry I had brought back to a friend. I was the only patient. The nurses were very kind to me. I was discharged from hospital several weeks later, only to find the men I had been training with had gone. I in the meantime had been on the Y list.

A few weeks after that, in early March, I was posted to Arborfield 212 Light AA Training Regiment. Arborfield was one of the oldest barracks in Great Britain. If I had a choice between Arborfield and Dartmoor Prison, I would have chosen the prison. A trick one had to learn at mealtimes. The dining hall was a large rectangular building with a wide gangway down the middle. The tables were placed with one end near the gangway and the other end near the wall. The trick was to sit as near to the outer wall as possible. The food was placed on the end of the table near the gangway. The soldier there had to dish out the food and pass the plates along. The soldiers sitting near the wall at the other end of the table got their food first and good portions. When the soldier serving saw that he would not have enough for the rest of the men he cut back on their portions. Those near the gangway had a lean time.

The whole regiment of AA guns went on a training scheme to Dartmoor. We arrived somewhere in Devon at nightfall. It was raining cats and dogs. We had no tents only a tarpaulin sheet which we rigged up. We were packed tight to avoid the rain. A Major turned up, an elderly man, and he asked us if he could squeeze in on the end. We made room for him. He was a gentleman, a very nice man. The next day we moved to Dartmoor Prison. We deployed around the Prison. We could see the Barrage balloons around Plymouth. We heard gunfire and saw shells exploding over the city. A German bomber flew over us quite low down. Not a shot was fired from our regiment of Bofors guns. They had not got one shell between them.

The next mobile scheme was taking the regiment of guns to Anglesey, through Wales. This time we had some ammunition to fire at our air-sock. While going through Wales we stopped at a small town. We had nothing to eat for hours. One of our men went over to a bread delivery van and the man gave him a loaf of bread which was devoured. We went over the Menai Bridge, fired at the air-sock and returned to Arborfield. On the way back through Wales, an old lady had two of us at a time for tea, a boiled egg and jelly. It was very kind of her.

Later, we were posted to Penhale Point in Cornwall. Penhale camp was on top of the cliffs. A bleak camp in a bleak place. The camp was divided into two: ATS girls in one half, and soldiers in the other. A fence divided the two. I've seen some different types of fences over time, but this one was the King. It was 14 or 16 feet high mesh. The mind boggles. One wondered if one of the ATS girls had a pet giraffe. Looking at the situation from a business point of view, one can see a comfortable income from selling line-props to the soldiers to pole-vault over the fence.

Some Americans were nearby experimenting with a radio controlled plane. It had a wing span of about 7 feet and was buzzing around most of the day. On a more sombre note, three soldiers went to nearby Newquay on the first day of arrival. As they returned later along the beach which had been mined. One was killed, one injured and the other escaped without injury. This was gross negligence on the part of the C.O who had failed to issue any warnings to the new arrivals. We completed our training and were posted to Selby.

Selby. 41st (5 NSR) Searchlight Regiment RA.

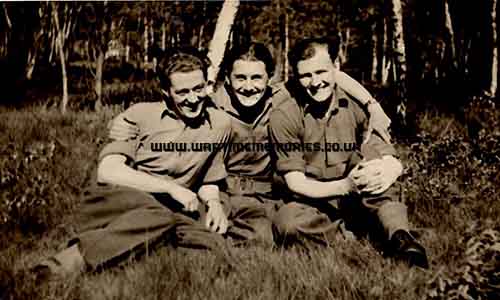

Three of us were on our way to Selby, the other two were smaller than me. One was Andy Stringer from Harrow and the other was Bob Midgely from Blackpool; we were all wireless operators. Bob was a professional drummer with the dance bands at that time. He used to get release for times to go and make records. I saw him years later on TV on Sunday Night at The London Palladium with Bruce Forsyth. Bruce playing the piano and Bob on the drums. We had left Cornwall by train, going through lots of stations all with their names removed in case of invasion. We arrived at York, were picked up, and taken to Selby. I was officially a Gunner, Driver, and Operator.

Selby was the H.Q. of the 41st which covered the whole of the Humber area. The H.Q. was a big house in large grounds. We were billeted in army huts about half a mile away. The regiment had been in the same place for some time. The method of communication had been telephone, but now we were going mobile it would be radio. They would need 50 radios for the whole regiment and 100 operators, two per set. We were given a Morris wireless truck, a radio, two remote controls, a Canadian chore horse for charging the batteries and two large batteries. We were supposed to get a watch, but I never saw one all through the war. They had been taken by the officers.

We were supposed to start operating at certain times, and messages received were supposed to be record time received. We moved to the S/L site on the other side of Scunthorpe, past the Appleby steel works. The two of us slept in a giant marquee. There were about 1500 personnel in the regiment, many were from Stoke and Tunstall. The wireless was made in London and was in a cardboard box. On opening the box we found the names and addresses of over twenty girls all single or engaged. We installed the radio in the wireless truck which were nicknamed a Gin-Palace, by bolting it down to the desk inside.

We were sent with the vehicle to Thorne to learn how to waterproof it for landing in France. The waterproofing was tested in a large concrete tank in a park. There were two water filled tanks, one for 15cwt trucks 4feet deep and the other for 1 Ton trucks quite a bit deeper. Our trucks were 15cwt. One driver for some unknown reason drove his 15cwt truck into the 1 ton tank. The engine stopped in the middle leaving just his head above water. The officer standing beside him with his swaggers tick under his arm, bend down and reached below the water. By the swirl of water at his side you could tell he had opened the door. He got out and disappeared under water. Just like a comedy film.

Eventually, the whole regiment moved to a large estate at West Chillington, inland from Worthing. The nearest railway station was Pulborough. The French Canadians had just left, they were known as tricky people who were very capable with a knife. For the first few days we had to sleep outside. A groundsheet on the heather, and a bed placed on top of that. We were warned to check the bed before we got into it in case of adders. There were harmless grass snakes and lizards too. There were plenty of reptiles about. On June 6th it was announced that the invasion had begun. In the afternoon thousands of planes flew over us on the way to France. Sometime later we moved to Worthing. We were given 48hr passes to go to London. We were told if we wanted to take the chance to go home we could. I went home.

When we returned we went on a night exercise with the radios on the downs behind Worthing. We saw our first V1, like a blowlamp with wings. The noise was tremendous. Andy Stringer who was expected to be my radio mate was told he wouldn't be. I found out the reason was he was not considered to be the best operator which I found to be true.

France

I believe the British and Canadians were shipped out for the invasion from Portsmouth, the Americans from Southampton. Our regiment was under the 31st (North Midlands) Anti-Aircraft Brigade, itself part of the 21st Army Group. Being in the American zone we were sent to Southampton. The port was organised and run by coloured Americans and they were good at their job. We arrived at night and the whole regiment were loaded on large liberty ships. The vehicles were driven onto large nets and were lifted into the hold. We set sail for Normandy on 6th of August 1944. We arrived at the south east coast of the Cherbourg peninsula (Utah Beach) The beach was a gradually sloping beach of sand. The liberty ships anchored some way off because of their large draft. In the evening I was on deck when I saw another Liberty boat about 1000 yards off start to sent a signal with an Aldis lamp, four words a minute was the best they could manage. It said 'Anchor for the night'.

The following day, 7th of August, we were loaded into landing crafts. Then, when the tide was at its highest, they ran the landing craft up the beach. We waited until the tide retreated and drove off the craft onto a dry beach. So much for water-proofing the vehicle! The regiment moved up to the Cherbourg area. The plan for Cherbourg was made before the invasion. It being the biggest port in the area and as masses of equipment and men etc would be required. The Germans still held the port, but our regiment was deployed around the port in anticipation of detecting enemy fighters. Our big searchlights were fitted with sound location detectors. One searchlight was to shine in a fixed position flashing letter A, dot dash. The position of any aircraft was to be given in relation to the fixed beam The fighter aircraft, US Black Widows, a twin fuselage plane, would be informed of the position of the enemy.

We were the only searchlight regiment in that area. Our battery was in the east, Battery H.Q. were at St Pierre Eglise. The first night we spent in a field near the place. We were on our own on one side of the field , the cooks were on the other side some 300yds away. We were given about 6 boxes of American Army emergency rations, breakfast unit, dinner unit and supper unit. They were very good. Our wireless truck was parked next to a hedge. We covered it with camouflage netting. During the evening a major turned up in British uniform Intelligence Corps. He was a well spoken man. He asked if he could spend the night with us. We said yes and gave him a cup of American coffee. He left the next morning. The whole of the Cherbourg peninsula was occupied by American forces, no British or Canadian forces were involve with the exception of our regiment. I later wondered what the British Intelligence officer was doing there. The Battery H.Q. was eventually moved into the big chateau at St Pierre. Our radio was placed in the very large loft space. The other radio was located nearby. The chateau had been the German naval H.Q. Operating the set at night was a bit weird, large bats with a 10inch wing span flew around our heads. I later hung some rods from the roof beams and the bats managed to avoid flying into any of them. The wireless had to be situated in a high location for the best reception. Our set was in contact with sector, the main control. The messages were telephoned to British H.Q. to pass on to the search-lights.

The plan to use Cherbourg never came about as the Germans held it for weeks, it would prove difficult to remove them without damaging the docks. Churchill's concrete Mulberry docks provide the solution. Once the troops had established themselves in the peninsula they started to move east. We had marvellous food all the time we were in the American zone. We had to go down to Valonges with our wireless truck as a link between two wireless stations which were too far apart. This lasted 4 days. The Allied troops defeated the Germans in the Falaise gap and started to move east quite quickly. We packed up and the regiment started to follow the advance. We knew this would be the end of the good food. We did, however, have a good chef. Corporal Jennings, a big grumpy man but an excellent cook. When we started to enter Rouen we were going down a slight hill with tram lines. We had to drive around a dead horse where French people were cutting off a Sunday joint. It was unbelievable the number of horses the Germans used. The roads were lined mostly with destroyed tanks and other vehicles. A 2 inch white tape was laid on the verge of the road to mark which had been checked for mines. My fellow operator Cyril Seldon was driving thorough Auxi-le-Chateau, when we noticed a bar called the Devonshire Arms. We went in for a drink. The Englishman who ran the place was more hostile than any German.

We arrived at the small village of Mezerolles. There was a large wood on a slope on the left with lots of huts in it. These had housed the slave labour used on the V1 site. They had been of all nationalities. A road from the wood led to a level piece of ground. The site on this ground comprised of a concrete ramp for launching, a sunken concrete pit with a very thick glass screen on wires for lowering to protect the occupants from the flames. We stayed there for about two weeks before moving on to Leuvan. We were billeted in the university. I found a big pile of Bosch magazines called Signal. At night we were on the wireless truck reporting on the number of V1s going over, i think towards the docks at Antwerp. It seemed one was going over every minute. They were far too fast for the searchlights and AA fire.

Belgium and Holland

We then moved to Brussels, near a big lake. Our wireless truck was alongside the road, we had the door open. Along came two Belgian girls who were interested to see the wireless truck. We let them come in to have a look around. Along came a Major (Battery C.O.) he said 'Get these girls out of here'. Later I had to go down to the local bank to get the money for the Battery. We slept in a large building that had been used by the German ATS.

We left Brussels and went through Ghent and Zelzate across the Dutch border to a place called Sas-Van-Ghent. Our battery was stationed there. The rest of the regiment was stationed about 10 miles away. We, about 4 of us, were billeted two floors up in a partly unused brewery. The height was necessary for reception. The cook house was in the basement. A very large canal ran by the side of us. Nothing like an English canal, this was 100yds wide and terrifically deep. It could take ocean going liners down to Ghent and beyond. We had arrived in October and stayed there until I left them in February. The war situation was more or less static. The allies had complete supremacy in the air. They were building up for the big push across the Rhine when the weather was better. Plenty of children aged from 7-16 came to see us. Two Dutch boys had started to learn English. One of them, Jan was very quick. He was a big lad, a very nice boy.

A Dutch girl of 17, Denise asked Bill Hood and myself if we would like to go to the cinema in Zelzate. She was as giddy as a goat. We decided to go. She brought a friend named; wait for it, Philomenia van der Bruge. We set off after dinner for Zelzate. About halfway there, we stopped at Denise's married sister's house for half an hour and then we crossed the border again to go to the cinema. We saw Disneys Snow White. We returned in time for tea. This was the first and last time we saw Philomenia.

Cyril Seldon and I used the 22 set in the brewery. The 22 set was a nice radio to use. It was powered by a vibrating unit and was much quieter than the 19 set. The 19 set was much more rugged however and could be used in Tanks. Denise came most days and on one occasion took us to meet her parents. One night in a local bar we met a man in his fifties who took us to his home. His first name was Gert, The walls of his home were covered in American film stars of the early 1930s, all were autographed and some were very large. It seems that Gert was in Hollywood in the 1920/1930s. He claimed he had appeared in the first talkie with Al Jolson. In the film Jolsons wife leaves him for another man, Gert played that man. Now he had a greengrocery business.

When outside at night in a clear sky I could see a small star moving across the sky. It was a V2 heading for London. There was no defence against these and no noise of approach for the victims. The impact was a very large crater and devastation on a wide scale. Just before Christmas we had notice of the start of the offensive in the Ardennes. We were told to carry guns at all times. The radio work at Sas-van-Ghent was just general army business, no active use. We had a nice Christmas, the cook served 7lb tins of Californian peaches from Normandy.

The Ardennes offensive took the allies by surprise. The German tanks had cover from the trees in the forest and the foggy conditions prevented Allied planes from action. Hitler had ordered the attack just as the troops in the East needed reinforcements. Once the fog had lifted the Allied planes soon defeated the tanks. Two replacements came to join us. A Bombardier (two stripes). The one we had in Normandy accidentally shot himself in the thigh. The other was a thick set individual, well spoken. His name was Digby Marriott, a Shakespearian actor. Apparently he was a replacement for me who was shortly to move on. One day we were told to get our towel and some soap as we were going to a Mobile Bath Unit. I didn't know they existed. Off we went, we couldn't recognise each other when we came out. After Christmas came a sharp frost which froze the canal near us. The Dutch lads fixed us up with some skates and we gave it a go.

581st Moonlight Battery.

A Sergeant from a unit near the sea told us an ME109 had landed on the beach and the pilot got out and said he had had enough. He spoke good English. Apparently he had been to an Oxford College. The German air force was now confined to airfields in Germany. Concentrating the targets for the more powerful Allied air forces. The job for a large searchlight battery became non-existent. So, at the end of February, I and many of our Battery were sent to Vilvourde near Brussels to form the 581st Moonlight Battery. We had not heard of this before, It was a brilliant idea. It's not shining the light into the sky, but illuminating the ground for engineers and infantry. Many of my friends were transferred to this battery. The total in the Battery was about 400. The C.O was a thin pale faced man with a moustache. We had heard that he was a former Spitfire pilot who had suffered with his nerves; (who can blame him) and had transferred to the Artillery. He had transferred from the 344th Battery to become our C.O. My fellow operator was from Luton a tall thin man with black curly hair. He was a carpenter by trade, but not all that good at wireless operating. We had a 15cwt truck with the noisy 19 set, a 160lb tent, a chore horse for charging the batteries, a Piat gun for launching bombs at tanks two tin boxes with three Piat bombs each, a Bren gun with ammo, two Sten guns with a wooden box full of 9mm ammo. I thought we were going to take on the Germans single-handed.

Our first port of call was Venlo on the river Maas. The town was deserted. We all slept in a terraced row of houses. Across the road was a railway marshalling yard. The searchlight was illuminating a bridge over the river for the Royal Engineers to repair. We were there for a few days before moving on. Germany. Sometime later we were travelling down the road from Xanten to Kalcar, there was a notice board on the side of the road which read 'Dust means Death'. We next stopped not far from the Rhine up a track with some farm buildings on the left and 4 Nazi built council houses not very old. We stayed about 10 days. One night I had to go with the wireless set into a room with Major Spens. One could hear the rush overhead of 25 pounder shells. The Major kept looking up in fear. We moved again to a small farmhouse near Sonsbeck. My fellow operator Ken and I slept upstairs, the lieutenant or sergeant were below. The serge and officer sang a ditty, the serge playing the piano. Here are the words.

Little Red Riding Hood was not so good and kept the wolf from the door. Father and mother she had none, Nobody knew where the money came from, No need to ask it, who filled the basket, The storybooks they never tell How could Red Riding Hood have been so good and kept the wolf from the door.

It was late March 1945 and we were near some stacks of large shells. The stacks were about 7foot 6inches high and 5yds by 10 yds. On March 25th the Allies launched the attack and crossed the Rhine at Wesel. The Rhine was a massive river with a fast flow. The day started with Dakota planes of paratroopers, British and Americans. More US planes towing big gliders that carried men and Jeeps. Others had large guns inside. The Dakota planes came back, some on fire. Some crashed within a mile and a half of us. We were hoping they didn't crash on those stacks of shells. Two days later we moved down to the Rhine itself. A pontoon bridge had been built across the river. A marvellous job in such a short time. I suppose our lights helped them to work through the night. They were a series of large boats tied together from one side to the other. The pontoon bridge was capable of taking tanks and large lorries. We drove across the bridge and stayed a night in a house on the other side of Wesel. There were no people visible at all. We moved on supporting the combined force of the 6th Airborne and 15th Highland Division. The Scots were first class troops and the Germans didn't like facing them. We went on eventually passing through Munster and on to Osnabruck where we stayed in an old German barracks. The German defences seemed to be fading. We carried on through Celle on the way to Uelzen. We stopped some distance from Eulzen on a minor road. There were no buildings in sight so we set up the 160lb tents in a field. There were about 25 of us. One was the ambulance man we called Doc. Another was Sgt Brown and another we called Trapper. He was Canadian and had indeed been a trapper in Canada. They all seemed old man to me aged 20. On the other side of the road was a small field and a conifer plantation, trees about 18feet high, beyond that we could see nothing.

In the evening while it was still light an ME109 came over quite low on the other side of the conifers. There was a barrage of Bofor gun fire, and the plane was shot down. In the next 5 mins two more came over and were disposed of in rapid time. The speed all three was shot down was astonishing. We had no idea that there were AA guns in the area. The quality of the German pilots at that stage of the war was much lower. By about this time Hitler did what he should have done 6 years earlier, he shot himself.

of the Wehrmacht army had given up any possibility of winning. The two units the 15th Highlanders and the 6th Airborne were split. The 6th moved to Palestine I was told and the 15th remained with us. We took our radio and a search light forward to illuminate Eulzen for the 15th to capture. The light shone forward and the Scots moved forward. Fighting could be heard all night. We were in a dicey situation, as the German big guns would try and knock out the lights. The Scottish lads came back in the morning having failed to take the town. It was said that some SS troops had been moved in to protect the town. The following night the Scots went in again, this time taking the town.

We moved on towards Luneburg. Plenty of German soldiers were moving behind the front line, they could see the game was up. We went past Luneburg towards Laudenburg to the River Elbe. The road to the Elbe was a gradual downhill slope to a wooded valley. On the way down there were hundreds of German soldiers walking the opposite way, without helmets of equipment. Many were removing their wrist watches and stamping on them. An old German bus came by loaded with prisoners. The British troops had nothing to do with the prisoners as we were in no position to feed them. On arrival at the River Elbe we saw a corporal in the Military Police with 10 prisoners. He was a very powerfully built man and he asked the prisoners if they had any weapons. They all said no. He searched the men and found a knife pushed down inside one man's boot. He held it under the Germans nose and said 'What's this?' The German looked frightened. The corporal gave him a powerful right hook, knocking him to the floor.

We moved on to Lubeck, where German prisoners were being temporarily held. Don Hartley, another radio operator and I went to a large villa with a large ornamental pond in front. Another soldier came along and told us that the men in his regiment had collected revolvers from the prisoners, but some had accidentally shot themselves. Their C.O. had orders all revolvers to be handed in. They had been put in 8 sand bags and thrown into the pond. After he had gone we decided to take a look ourselves. Don put on his swimming trucks and got into the pond. It only came up to his knees. We got all 8 bags out and looked through them. Don took a Browning 9mm with leather pouch and spare magazine. I chose a Polish Radon 9mm also with a spare magazine. The rest were returned to the pond.

We moved up towards Kiel about 3rd of May 1945. We never saw any other British soldiers up there. We must have been the first in that area. The German civilian population were not visible at all. I think the knowledge of the concentration camps left them in fear of the invading forces. We arrived at Kiel town all 30 of us. We rode down the main street which had been heavily bombed. There was a Woolworth which had been destroyed. The German civilians at last appeared, lining the street in silence. I suspect they preferred to see us rather than the Russians. The road went down towards the harbour. Keil harbour stretched West to East towards the Baltic Sea. The North side of the harbour had the U boat pens. We approached the South side. The war was not yet over. As we rounded a bend there was a German soldier on guard with his rifle. It was the entrance to the AA site on high ground to the right. He did nothing and we did nothing. We continued around the South side of the harbour. The Lieutenant was looking for somewhere for us to spend the night. He pulled us up in front of a row of terraced houses. He knocked on the first door, an old German answered. Luckily, he could speak English. He had been a merchant seaman before the war travelling between Germany and America. The officer asked if 5 of us could sleep there just for one night. He said yes. The officer knocked on the next door. It was answered by a woman of maybe 35 to 38. She could not speak English and our officer had no German. This is when the comedy started. He put hand up indicating 5 to sleep in her house. She went hysterical. She thought she was in for a night of unwanted passion with 5 of us. He got the old German Sailor to explain the situation to her and she calmed down.

Next day the officer went in search of alternative accommodation. He returned; he had found somewhere. The previous occupants had gone. It was a sort of holiday residence further along the road. The road was not a road in the true sense of the word, but led to another property a little further along. On the other side of the road to our place was a sandy beach and then the harbour. The water was covered in oil from the boats. The rest of our battery was further along to the East of us at a place called Laboe. Our billet was a biggish place, with large rooms downstairs and up and a view of the harbour from upstairs. On the other side of the harbour was Friedrichsort the U Boat place.

At water level was a string of train like tunnels all side by side, there must have been 10 or more. They were the tunnels where U Boats were repaired and protected from air raids. Next door to us was a large house in which lived an elderly lady, a Countess. She could speak fluent Japanese and English. There was also a very pretty girl about 24 years old who could also speak English. She said her husband was a U-Boat commander and told me the number of his boat she asked me if I saw a U-Boat with that number coming into port would I tell Her. I said I would. I only saw one U-Boat come in, but it was on the far side and I couldn't read the number. There was a ferry that ran from Kiel to near to us. Loads of people came over to have a look at us. We had plenty of children come to see us. Two sisters Ingrid who was twelve and Sigrid who was 8 and both very pretty came. I gave them a small bar of American soap I had picked up in Normandy. It was called Bridal Bouquet and smelt very nice. They gave me two photos of themselves, which I still have in my album.

There were no military boats in the harbour only small canal type boats with little cabins. There was one larger ship that had a motor boat on board that could be lifted on and off by a crane. All those on the boats were confined to ship and food had to be taken to them. One day, the captain of the large ship had obviously had enough of being cooped up in his ship. He had the crane lower the motor boat and he took if for a spin around the harbour. The British troops went in pursuit but we not quick enough to catch him. After a while he must have felt better for his outing and went back to his ship and had the motor boat stowed on board again. One of the British guys from London found a reasonable sized rowing boat, fitted it up with a pole and sheet and took some of the local children out sailing around the Harbour.

Then August came along Germany was returning to peaceful activity. The searchlight units had been formed at the start of the war and as such have been amongst the longest serving. Many were demobilised, which meant the mission at Kiel was over.

The rest of us were moved to Preetz just south of Kiel. We drove over the canal bridge, A very high structure built to allow battleships to sail under it. We were stationed in an anti aircraft site, with concrete tunnels and a loudspeaker system. A lorry used to take the men to Kiel each night, it was called the The Passion Wagon. My mate Ken Watts and I went into Kiel, it was not a big place. The main street sloped gradually down to the harbour. On the main street was a big theatre where I went to hear Kiel symphony orchestra place Tchaikovskys 4th and 6th symphonies. There was also a small bar called The Empire Bar. It sold first class beer brewed in Munich for 3d a pint. I expected it to be full of other soldiers, but there was only one soldier in there from the Pioneer Corps.

After a while we were posted the the 63rd Anti-Tank Regiment, Argyll and Sunderland Highlanders. This was at Kiel Friedrichsort the U boat harbour. The barracks were very old and had been used by the U Boat crews. As the end of November arrived the weather became much colder. Someone decided we needed to have a practice shoot with the 17 pounder anti-tank gun. We were given Tank suits to wear. These were heavy duty one piece suits. We were loaded into a lorry and taken to a field on the coast . The field was over 1000 yards long and sloped down to the sea. The target was to be an old tank. There were several small fishing boats with sails just off the coast in line with the tank. The 17 pounder was a tank with a rotating open top turret The sergeant was in the tank with a soldier who loaded the shells. The shells were long and heavy. Somebody asked 'What about the fishing boats?' The sergeant said 'They'll move.' How right he was, after the first shell they quickly moved to the right or left. I was passing shells up to the tank. The sergeant said 'You next' I said that I hadn't fired a gun before. He said 'You are going to fire one now.'

Three weeks before Christmas 1945 I was transferred to an Anti-Tank Regiment in the Hertz Mountains. I went with two other soldiers. It was a long way and we arrive at HQ in the evening at Braunlager. Several more men arrived and we were sent to a battery at St Andreasburg. This was a nice place and we were billeted in a very large hotel. The windows were double glazed to keep out the cold. Outside the frozen snow crackled under your feet. It was bright sunshine every day, but the snow never melted I had three mates there, Ted Lewis from Upton Magna near Shrewsbury, Reggie West from Brighton and Donald Booth Berry from 25 Green St, The Bulk, Lancaster. Down the road from the hotel was a house with the upper floor turned into a bar. Carl and Heinz two elderly Germans served beer there. At the camp skis and sticks were available for anyone who wanted to try skiing. We had some instruction in skiing and I spent every afternoon skiing in the bright sunshine. There were German children aged about five or six who were skiing around us. They were brilliant on skis. I looked forward to skiing and was enjoying myself when an NCO arrived and told me the Commanding Officer wanted to see me. He told me that the Army were offering a series of courses at a college and each regiment was to send four men. He asked me if I wanted to go saying it would only be for three weeks. I was enjoying my skiing so much I said I would rather not. He said each battery had to send one man and that I was the only one eligible to go. I thought the rest of the battery must be a thick lot. I was sent, with another three men from the regiment to Bomlitz just outside Fallingbostel. Two of the other men were Jewish, one from London who never spoke and the other from Manchester, who had a good Lancashire sense of humour. The other guy was called Stokes from Wolverhampton. He asked me where I came from. South Derbyshire I said. Whereabouts? he asked. I said a small village called Hartshorne. To my surprise he knew it. He was evacuated at the start of the war to Woodville the next village along the road. He was placed with a family called Wells who used to ride a motorcycle and sidecar and sold cloth.

There were 300 men, privates, NCOs and Officers due to take the courses. After some initial tests, I was put in top set for maths course. There were six of us including Stokes, all privates no NCOs or Officers made it into the top set. A captain took us for Algebra and Calculus. The three week course turned into six weeks.

One day a bunch of us were sent to the dining hall. We were told to put out the chairs for a film show later that morning. The film show consisted of two films. The first was about Personal Hygiene. We were shown body lice that appeared to be the size of cows on the big screen. The second film was an horrific film about VD. Several of the men fainted and had to be carried outside as it was too much for them. Later at dinner only 25 of us showed up.

The regiment was moving to Fallingbostel, two miles from Bomlitz. Fallingbostel camp was the greatest military complex one could wish to see. It was made up of a series of rectangular formations. Each formation was made up of two rectangular buildings running up each side and two larger buildings at either end to form the rectangle. One of the larger buildings was the cookhouse and dining hall and the other building was a place where troops could go for a cup of tea or see any shows that were put on. We were upstairs, five to a room on the first floor. These rectangular formations stretched for miles.

Fallingbostel village was a couple of miles away. Belsen was about six miles away and two the east of the camp was a POW camp. This camp had held US and British prisoners during the war. There was a small cemetery close by with a few US and British troops who had died in the camp. Now the camp held a mix of nationalities of a suspicious nature. Our regiment sent a guard of thirty men each night to perform guard duties. There were eight German Shepherd dogs trained to be handled by one specific soldier. They would not allow anyone else near them. There were also some Polish soldiers sharing guard duty.

The camp had wooden huts in the middle for the prisoners and was surrounded by a 14ft high wire fence which had guard towers every so often. The guard towers had a Bren gun and magazines of 29, 303 bullets. While I was on guard a Dutch man came up and said he shouldn't be in there. I knew why he was there. Quite few Dutch men had volunteered to work with the SS.

One evening I saw bright lights coming from the guardroom. An officer and NCO came out of the door. All at once an German Shepherd broke loose and came running at them. The officer drew his P38 revolver and the two rushed back into the guardroom. They had to phone the regiment to get the dog taken under control before they could leave.

After all the interrogations were completed the camp was closed. At the entrance to our barracks was a notice board with all the standing orders posted. I noticed that one day it had a list of articles for sale. You had to put your name down against any article you liked and wait to see if your name was drawn out of the hat. I put my name down for a camera. Later my mates had seen that I had put my name down for the camera and they did the same hoping to increase my chances of getting it. Reggie West was drawn from the hat and gave me the camera. It cost £2. It was a Voightlander Focussing Brilliant with a leather pouch and shoulder strap.

30 names appeared on this notice board including mine for duty escorting 600 prisoners from Munster lager to Antwerp, then they were to be shipped to the UK to pick fruit. The next day we were given Sten guns and ammo and taken to Munster Lager. We were met by a young Lieutenant , a tall thin man with glasses. He wore a small beret and had a belt around his waist with a p38 revolver in a holster. He said 'Today our duty is to guard these prisoners all the way to Antwerp. If any try to escape don't hesitate to shoot. Then report 1,2,3 or 4 bods you have shot.' This was 12 months after the war had ended. I thought we have got a right one here. The prisoners were loaded into carriages. At the end of each carriage was a open semi-circular platform surrounded by a metal fence. This is where the guards were stationed. The officer gave the signal and the train moved off very slowly. It was a beautiful day and the prisoners were hanging out of the windows, waving hand-kerchiefs at the general public who were waving back. A little while later we passed slowly through a small station. An old man was sweeping the platform. One of the prisoners shouted something to the old man and threw his bag with his stuff in onto the platform. The old man replied. At that moment the officer stopped the train, got off and unbuttoning his holster drew his revolver out and aimed it at the old man. He indicated to the old man to get on the train. The old man like the rest of us was astonished. The old guy began to cry. The officer said we will take him twenty miles, drop him off and give him a bloody good walk back. I thought 'You evil pig'.

We carried on slowly and were going through a wood yard when I heard a clatter of Sten guns I was told a prisoner was trying to escape with a load on his shoulders the size of a small piano. I never heard of any prisoner being killed or wounded. I suspect the ammunition was blanks. We pulled into a station at Ham, I got off the train on the track side and walked down beside the train. I came to a platform with no guard on it. The prisoners had come out onto the platform. I aimed my Sten gun at them and waved them back inside. I thought that if someone was going to try to escape, they would try when the train starts to move off. I hung on to the side of the train with one hand, holding the Sten gun in the other. I could see all the way down the length of the train. Sure enough as the train started to move, one jumped off. I ran back down the track. I saw him dive under a goods truck. I gave a burst from my Sten gun, but thankfully he had gone. I felt these guys had been through enough and he would probably suffer much more trying to get home. When we eventually arrived at Antwerp, we walked them down to the docks. They were talking to us and shook hands with us when we left.

There were lorries at Fallingbostel to take you into Hamburg at the weekend. It was a one and a half hour ride. In Hamburg there was a large hotel with several floors. The first floor had a bar serving beer all day. The second floor housed a large restaurant complete with a string quartet and waitresses. At Christmas we had Christmas dinner with Turkey and Christmas puddings served to us by the officers.

In February 1947 my four room mates were demobbed, so I was on my own. I went down to the telephone exchange. It had 70 lines with three reserved for dialing outside lines. I shared operating duties with some other lads. It was quite busy at times. Just before the war a large Autobahn was being constructed nearby and there were large piles of sand. A group of us would go and sit on these piles of sand sun bathing.

The sergeant came to me one day and said, 'You'll be operating a wireless set tomorrow. You will be in a jeep with a 19 set and a driver. You are going to Luneberg Heath and you will be towing the target for 17 pounder target practice.' The following day I set off with a new recruit driver. We towed the target back and forth being in contact with the gun the whole time.

A few weeks later before I was due to be demobbed I was told to report to another battery. When I arrived I went into a room. There sitting at a desk was Stokes the guy I went on the course with at Bomlitz. He was now a sergeant. He said 'You sign on for another three years and you will get three stripes too.' I told him I had had enough and that I wanted to go home.

On June 17th 1947, Don Berry and I were demobbed at York. It was Farewell to Arms. Fours years of my life, which contained everything that I am glad I never missed. All the wonderful people you encounter.